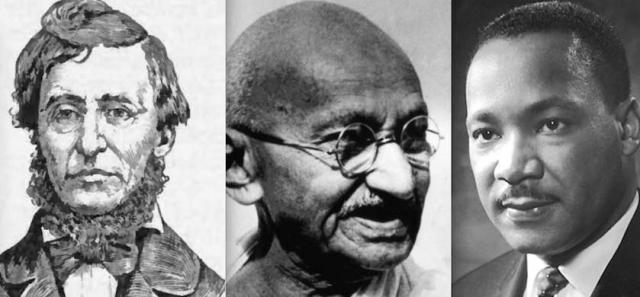

I never met Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., or attended a march or rally where I could hear him speak, but on the evening of April 4, 1968, an hour or so after he was assassinated, I was in a jail cell in Concord, Mass. writing a freshman paper about King, Gandhi and Thoreau, and their shared ideas about the power of non-violent political protest.

It had all started out when I found myself with a classic case of writer’s block, unable to get started on an end-of-the-term paper for my philosophy class at Wesleyan University in Connecticut. The topic I had chosen was tracing Martin Luther King’s political roots back through the thought and practice of Indian independence leader Mohandas Gandhi and philosopher and anti-war protester Henry David Thoreau.

Stuck for words, I decided on a whim or in desperation on the morning of my birthday to hitchhike, for inspiration, up to Concord and to Walden Pond, where Thoreau famously had built a small cabin in which he was living when he wrote Walden, and also his famous and hugely influential essay On Civil Disobedience — the latter work by way of explaining his decision to refuse to pay his taxes because of what he considered the United States’ illegal war against Mexico.

The US was, of course, at the time of my little pilgrimage, waging a similarly illegal and far more vicious and destructive war on the people of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia — a war that I had already decided a year earlier that I would not participate in.

I had, the prior October, gone down to Washington DC to join the historic Mobe March on the Pentagon, and had been arrested on the Mall of that huge building dedicated to war, spending several days locked up in the federal prison at Occoquan, Va. on misdemeanor charge of “trespassing” on federal property and, because I had gone limp and forced the marshals to carry me, “resisting arrest” (I got a five-day suspended sentence and was fined $50).

I had made a firm decision while still in high school that I would not allow myself to be drafted, and was waiting to be called up, when I would have to face the consequences of that refusal, having decided not to file for a student deferment while in college, which I decided was unfair to those young men who were not able to go to college to escape the war. (My being called up became a certainty later when the draft lottery was established and my number came up as 81.)

One of the big influences in my decision, shortly after my 18th birthday in 1967, to go to the local draft board and register for the Selective Service, at the same time telling the woman staffing that office that I would not allow myself to be drafted, was reading about King’s momentous address at Riverside Church in New York, made on April 4 of that year, in which he clearly linked that criminal war and its violent repression of the Vietnamese people to the brutal racism and class struggle at home in the US. (I urge all those reading this piece to take the time to read his remarkable, revelatory, heartfelt and sadly prophetic address in full or, better yet, listen to him deliver it ihimself here.) It was a lot to take in for an 18-year-old high school kid but King made it crystal clear that all these things were connected, and that making real change meant tackling them all, with a broad coalition. (Many, myself included, believe that it was that speech, so dangerous to the Establishment power structure, that sealed King’s fate a year to the day later, with a bullet whose timing seemed ominously designed to send exactly that message.)