A book review of:

MY LAI: VIETNAM, 1968, AND THE DESCENT INTO DARKNESS

By Howard Jones

Oxford: 2017

[Click here to return to Part One]

(Continued)

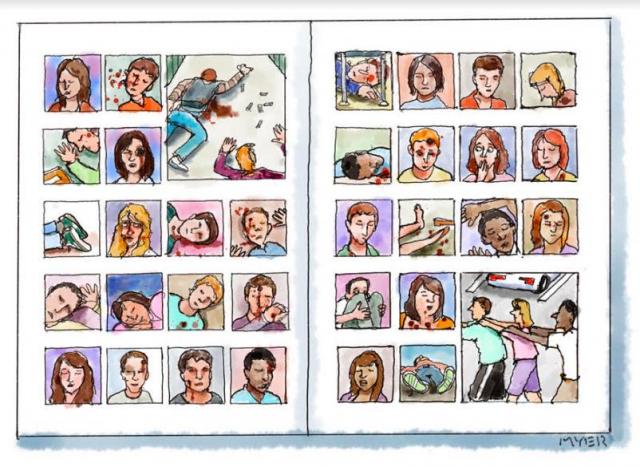

First before the bar at Fort Hood, Texas, in November 1969 was Calley’s platoon sergeant, David Mitchell, whom witnesses described as someone who carried out the lieutenant’s orders with particular gusto. Then in January it was Sergeant Charles Hutto’s turn at Fort McPherson, Georgia. Hutto had admitted turning his machine gun on a group of unarmed civilians. These two men were so patently guilty in the eyes of their own comrades that theirs were among the strongest cases the investigators had constructed for the prosecution. Both men were acquitted in trials that can only be described as judicial parodies.

At Mitchell’s trial the judge, ruling on a technicality, did not allow the prosecution to call witnesses with the most damning testimonies, like Hugh Thompson. Hutto had declared in court that “it was murder”, but claimed “we were doing it because we had been told”. When the jury refused to convict him because Hutto had not known that some orders could be illegal, Jones nails how the court was sanctioning “the major argument that had failed to win acquittal at Nuremburg”.

Shortly after Hutto’s trial, the Army dropped all charges against the remaining soldiers, fearing their claims to have been following orders would likewise find merit in the prevailing temper of the military juries. Heeding the judicial trend, Lieutenant General Jonathan Seaman, a regional commander exercising jurisdiction over officers above the rank of captain, dropped all charges against Major General Koster. By some opaque calculation that convinced no one, Seaman had concluded that Koster was not guilty of “intentional abrogation of responsibilities”. A hue and cry followed in the press and on Capitol Hill, denouncing Seaman for “a whitewash of the top man”. The outcry did prod the Pentagon to take punitive action against Koster. The general had already been dismissed as the commandant of West Point, and he was now demoted to brigadier general and stripped of his highest commendation.

Seaman informed Koster, through internal channels, that he held him “personally responsible” for My Lai, a kind of symbolic snub among gentlemen. But in exonerating the Americal commander, Seaman had — by design, it can be argued — inoculated the higher reaches of command, right up to General Westmoreland, from being held responsible for the actions of their subordinates, a blatant act of duplicity in light of the ruling at the Tokyo trials after the Second World War, where a lack of knowledge of atrocities committed by his troops had not prevented General Yamashita from being sentenced to death.

With Calley’s court martial already in progress, only three other officers remained to be tried: Medina and the Task Force Barker intelligence officer, Captain Eugene Kotouc, for war crimes, and 11th Brigade commander Henderson, for the cover-up. Jones deftly unspools how the flawed and self-protective system of military justice enabled trial judges in each case to provide improvised instructions to their juries that all but dictated the acquittal of all three men. Kotouc had been charged with murdering a prisoner, whom, given the available evidence, he almost certainly had; still the jury found him not guilty in less than an hour. Asked if he would stay in the military, Kotouc gushed, “Who would get out of a system like this … it’s the best damn army in the world.” 2