I grew up in Storrs, Connecticut, a faculty brat in a university town where minority people were few and far between. There were a few black kids in our high school — the children of people employed at UConn. There were also working-class Puerto Ricans in the area — American citizens but who knew that back then? — who had fled north from the economically devastated US colony of Puerto Rico to work in a big textile mill in nearby Willimantic.

Storrs was a liberal community. The civil rights movement and later the early anti-Vietnam War movement both had early and active support there, our school teachers were for the most part liberals who went beyond the core curriculum to teach us to question things, and (within limits) to pursue our ‘60s-era interest in alternative life-styles and politics.

But I did get a sense for what real racism was about, despite living in such an island of liberalism.

My mother was a native of Greensboro, North Carolina, and her parents still lived down there, just outside of town in a huge log cabin on a pond. Grandpa, a decorated mustard-gassed veteran of World War I, and a super-patriot, was a no-nonsense coach and headed the physical education program for the segregated Greensboro School District.

A generous-hearted woman who left home to serve as a Navy WAVE during World War II, my mother ended up posted at the Brooklyn Navy Yard for most of the war. After meeting and marrying my Dad, and moving to Storrs, where the University of Connecticut had hired Dad as an electrical engineering professor, she become quite liberal in her views, including on race. (Though one vestige of her upbringing — a conviction that mixed-race marriages would never work out — never left her. “Think of the children!” she would say when I’d argue with her, as if it were obvious.)

I remember back in the ‘50s, when I was probably about 8 or 9 years of age, that we drove down to Greensboro to visit my grandparents. It was before the days of the interstate highway system, and in the heyday of that ubiquitous roadside rest stop, Howard Johnsons, a favorite of all travel-weary kids because of the many flavors of ice cream they sold.

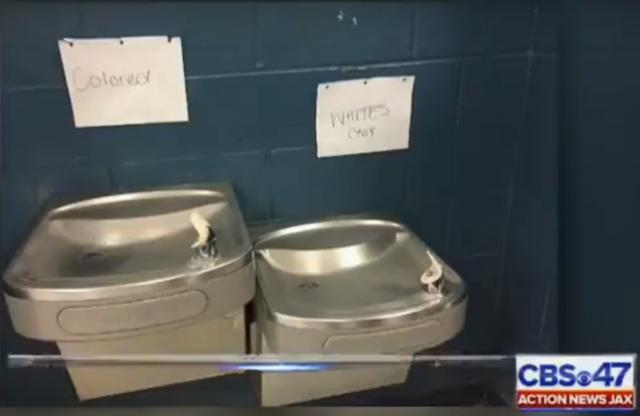

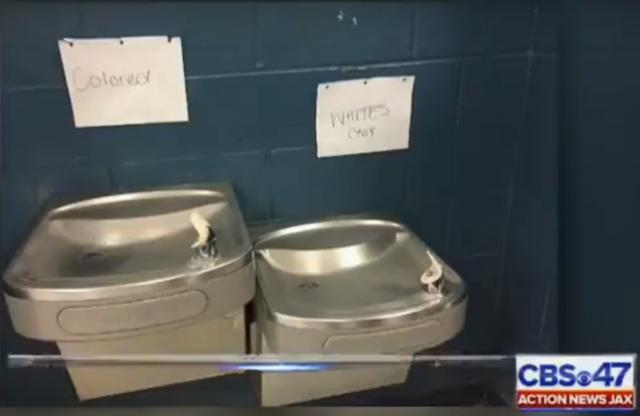

When we had crossed over into Virginia, and came upon one of those orange-roofed icons, dad stopped the car and we all piled into the cool lobby. I headed for the men’s room, but was caught up short by the sight of two fountains along the wall, with signs saying “whites” and “coloreds.” I asked my dad what that meant, and he explained to his wide-eyed son.

The idea of people with different skin color having to drink from different water fountains seemed bizarre to me, and I remember going to the colored fountain, more out of curiosity than rebelliousness, because I wanted to see if the water was different. (I don’t know what I expected: colored water?) My mother got upset — I suspect because from her upbringing she was used to such things and probably worried that it might create a scene.

Then I went to find the men’s room and was this time confronted by four, instead of two doors. That really floored me. Even at that young age, I knew that shit and piss were unpleasant smelling and dirty whether they emanated from white or “colored” bodies. I like to think I went into the “colored men’s” restroom, but I can’t remember what I actually did.

I left that Hojo’s with my mind jolted. Now I was noticing lots of black people as we drove along deeper into Dixie, and it was obvious that they were poor, living in usually unpainted shacks and mostly walking, while the whites we saw were driving nice cars and living in nicer houses, where one didn’t notice any black people.

This article was written on assignment for Salon.com. To read the full story follow the link below

This article was written on assignment for Salon.com. To read the full story follow the link below