When New Jersey State Senator Ronald Rice roadblocked legislation to legalize adult use of marijuana in the ‘Garden State’ last year he cited a litany of long debunked theories and specious assertions like legalization will inundate minority communities with “marijuana bodegas.”

The stance of Rice, an African American, helped stall efforts by New Jersey’s Governor and civil rights organizations to end racial inequities related to marijuana laws, like pot possession arrest rates for blacks being much higher than arrests for whites despite similar usage rates among the races.

Ending documented racism in enforcement of marijuana laws is a key impetus for efforts nationwide to end the prohibition on pot. That prohibition is rooted in federal legislation initially approved in 1937. That legislation was the culmination of the ‘Reefer Madness’ campaign that contained clear strands of blatant racism.

An analysis released in November 2019 by ACLU-NJ stated blacks in New Jersey are three times more likely to face arrest for marijuana possession than whites. While that arrest factor is 2.3 higher for blacks in Senator Rice’s legislative District, that disparity spikes as high as 11 times more likely in one legislative District and over 9 times more likely in two Districts adjacent to Rice’s District.

That ACLU-NJ analysis noted a 35 percent increase in pot possession arrests across NJ between 2013 and 2017. Additionally, that study criticized the annual expenditure in New Jersey of more than $140 million for enforcement of anti-marijuana laws.

A 2017 ACLU-NJ study found that the New Jersey state legislative district with the highest per capita rate for marijuana possession arrests was the district represented by Rice: the 28th Legislative District. Rice’s district contains portions of Newark, the state’s largest city where Rice once worked as a policeman and served as a City Councilman and Deputy Mayor.

Racial inequities embedded in marijuana law enforcement and now economic-related inequities surrounding the legalized medical/adult-use markets are well documented.

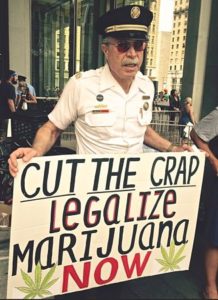

Politicians, police, prosecutors and media pundits have, historically, played prominent roles in resistance to reforms in pot prohibition. And, historically, the stereotypical public face of that resistance has been conservative and white. However, frequently overlooked in societal support for keeping marijuana illegal are ‘black faces.’

Many black politicians, preachers and other leaders – through either advocacy or acquiesce – have opposed marijuana law reform despite irrefutable evidence that pot prohibition has bludgeoned the black community leaving millions with arrest records that cripple economic and educational opportunities. Compounding the damage from arrest records is the added burden for some of having endured incarceration for marijuana law violations where imprisonment carries a separate lifetime stigma.

Philadelphia, Pa is 33-miles south of the NJ’s State Capitol Building in Trenton where Senator Rice and a few other blacks were among the legislators that scuttled the marijuana legalization effort in March 2019.

In Philadelphia, during the two terms Michael Nutter served mayor, city police arrested over 20,000 blacks for marijuana possession, leaving those predominately male arrestees with the lifetime stigma of arrest records.

In 2012, the first year of second mayoral term of Nutter, an African American, Philadelphia police arrested 3,052 blacks for pot possession compared to just 629 whites. That arrest disparity was partly attributable to the racial profiling Stop-&-Frisk police enforcement championed by Nutter and implemented by Nutter’s Police Commissioner who was also an African American.

In 2015, the year after Philadelphia decriminalized marijuana possession over the vehement objection of Mayor Nutter blacks still comprised 82 percent of the pot possession arrests…albeit a smaller number of possession arrests due to decriminalization. Philadelphia’s city government saved over $2 million in the decriminalization switch to traffic ticket like citations for marijuana possession busts instead of the previous formal arrest procedure with costs that included fingerprinting, police overtime pay, paperwork and court hearings.

In 2012 when voters in Washington State considered legalization of marijuana, many black ministers in that state assailed their African American colleague, the Rev. Carl Livingston, for his support of the legalization effort…that succeeded. Livingston, a political science professor at a college in Seattle, said he supported legalization due to his opposition to racist law enforcement that drives mass incarceration. Blacks comprised 70 percent of the pot possession arrests in Seattle despite being just three percent of that city’s population.

In 2010 when Californians were deliberating an ultimately unsuccessful ballot measure to legalize marijuana, a coalition of black ministers demanded the resignation of California’s NAACP president because of her support for legalization. That NAACP head saw legalization as a civil rights issue due to gross racial disparities in pot law enforcement.

In 1975 black political and religious leaders successfully stopped an effort on the City Council of Washington, DC to decriminalize possession of marijuana. Arrests of blacks for possession in DC had soared from 334 in 1968 to 3,002 in 1975. One black minister who was a DC City Councilman feared the city would become the marijuana “capital of the world” with decriminalization while a black DC City Councilwoman demanded that young people “be taught to obey the law.”

In 2017, over forty-years after DC black leaders blocked efforts to blunt racist marijuana enforcement practices, blacks comprised 90 percent of possession arrests in America’s capital city. DC’s Congressperson, Eleanor Holmes Norton, issued a press release in May 2017 stating reform of marijuana laws is “a civil rights issue in our city.” Holmes’ opposed congressional blockage of legalization approved by DC voters.

Many black supporters of continued anti-marijuana laws are seemingly oblivious to the racist roots of pot prohibition.

Bigoted U.S. President Richard Nixon launched his “War on Drugs” in 1971 with an ulterior motive to weaponize anti-narcotics laws, including pot prohibition, to demonize and destroy the Black Power and civil rights movements.

Harry Anslinger, the racist federal anti-narcotics head who secured passage of the 1937 pot prohibition law, once said marijuana “makes darkies think they’re as good as white men.” Anslinger frequently fanned fears that marijuana caused white woman to desire sex with black men, particularly jazz musicians.

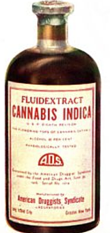

For decades prior to that federal law barring both the possession of and research about marijuana, pot was a widely utilized medicinal compound in the United States and Europe. Medical substances containing marijuana were sold over the counter and advertised in newspapers, including a newspaper published by a black religious denomination.

The nation that spearheaded the outlawing of marijuana on the international level in the mid-1920s was South Africa, the country where abhorrent apartheid existed at the time.

Many supporters of maintaining pot prohibition utilize myths.

New Jersey Senator Ronald Rice frequently trots out the ‘gateway’ theory that marijuana produces addiction to narcotics. That is a theory debunked by repeated reports from governmental bodies stretching back over a century.

For example, the study released in 1944, conducted by the New York Academy of Medicine for the Mayor of New York City stated “use of marijuana does not lead to morphine or heroin or cocaine.

The 1925 study on American soldiers stationed in Panama commissioned by the U.S. Army found “no evidence” that marijuana is a “habit-forming drug.”

In a March 2019 Open Letter opposing legalization that Rice distributed to his legislative colleagues, he declared, “We know that marijuana increases mental issues.”

Yet the 1894 report by the British Indian Hemp Commission concluded that marijuana in moderate use “produces no injurious effects on the mind.” That Commission was the first large-scale study of marijuana by a national government. That Commission, in preparation of its 3,281-page report, conducted 1,193 interviews in 30 cities across India, a country where use of marijuana for medicinal, spiritual and euphoric purposes spans thousands of years.

Ironically, anti-legalization Senator Rice, who has a reputation for advancing interests important to African Americans, supports expungement of marijuana arrest records and decriminalization. Rice introduced a decriminalization bill a few years ago, a measure drafted with assistance from the anti-marijuana NJ Responsible Approaches To Marijuana, an organization Rice has worked with.

While Rice opposed legalization, he did not oppose the legislative push to place the question of marijuana legalization on New Jersey’s November 2020 ballot for the voters to decide.

Unlike Rice, one of his African American colleagues in the New Jersey Senate, Shirley Turner, opposed both legalization and the ballot referendum on legalization. Turner was one of only two Democrats who joined the 14 NJ Senate Republicans to oppose that referendum.

In Turner’s 15th Legislative District – that includes Trenton – blacks are nearly three times more likely to face pot possession arrest than whites.