The spectacle of warfare, whether by intermittently shocking its public or inuring it to the horrors of combat, serves to normalize a permanent war economy and to make peace an anomaly.

Jan Mieszkowski, Watching War

I wasn’t sure what hat I should wear watching the Ken Burns and Lynn Novick PBS documentary The Vietnam War: An Intimate History. Should I be a professional Vietnam veteran, something I have stooped to? Or should I be a journalist, a fiction writer or a documentary filmmaker? I’ve done all these things. Maybe I should be an anti-war activist, something I’ve done (some say badly) for over 30 years? I’ve worn all these hats in the context of the Vietnam War. In the end, identity is a fluid and willful thing selectively mined from experience; like everyone else, I’m a human being doomed to live in ever-changing contexts. Holding on to the past is a trap.

One of the many images from Vietnam used to tell stories in the film

One of the many images from Vietnam used to tell stories in the film

Like Magritte’s famous painting of a pipe titled “This is not a pipe,” the Burns/Novick film is not “Vietnam” — it’s a TV drama. Questions about historic accuracy and political bias will likely always haunt it. It’s sophisticated cinematic production values and the story-telling questions they raise are important. In one sense, it’s a classic PBS documentary. But, then, it’s breaking some kind of ground in its mode of telling. If there’s a continuum between fiction and non-fiction, this film is somewhere in the middle; let’s call it a hybrid — in a no-man’s-land or DMZ between fiction and non-fiction. For any work of representational art, constructing a clean narrative from the chaos of life means leaving things out. That’s how narrative is refined and distilled. It also opens such a project to criticism from many angles. The use of metaphor and symbol are tools in the process of making sense out of the unfamiliar and the confusing. Without the essential reductiveness, art would be like that Borges story where the map of a country is a 1:1 ratio to reality — exactly the same size as the country itself.

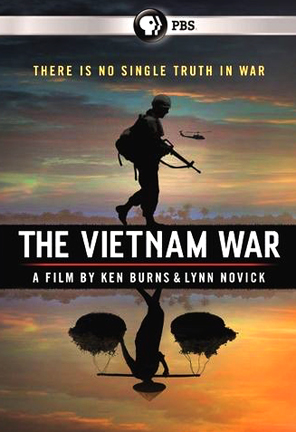

Burns and Novick say their goal was “to comprehend the special dissonance that is the Vietnam War. … We vowed to each other that we would avoid the limits of a binary political perspective and the shortcuts of conventional wisdom and superficial history.” They refer to the war as a “Rashomon of equally plausible ‘stories.’ ” Thus, the slogan they put on the movie poster: “There is no single truth in war.” As I watched the first half of the epic unfold, I constantly mulled over the question whether it was true “there is no single truth” concerning the Vietnam War. For one, the slogan seems to contradict itself. I would submit there is a single truth concerning the Vietnam War: It’s the fact the Vietnamese people never did anything against the powerful, imperial people who invaded and devastated their country for over a decade. Lately, I’ve challenge anyone to come up with anything hostile the Vietnamese, our WWII ally, did to us to deserve what we did to them. Self-defense doesn’t count. This single truth is hard to dispute, even when it’s swamped by an impressive melange of “intimate” cinematic stories set down in the weeds of war where killing is a self-reinforcing, circular nightmare. As many combat vets will tell you, once the firefight starts it’s only about killing those who are trying to kill you and your comrades. There’s the old truism, the first casualty of war is the truth. That, of course, is another single truth.

Burns and Novick (sitting together on the left) and their filmmaking team

Burns and Novick (sitting together on the left) and their filmmaking team

The many creative techniques used in the film hit us from the very first moment. The series opens on a black screen with the characteristic fwop fwop fwop of a Huey chopper. It’s an iconic aural “image” established in the American cultural consciousness from a host of popular Vietnam war movies like Apocalypse Now. By now, it’s a familiar metaphor accessible through the ears. The sound instantly puts our minds “in” Vietnam, and we’re buckled up and ready to sink into the weeds of the individual stories to come. Beautifully layered sound is everywhere: crunching feet on dirt roads; the subtle sound of bodies pushing through bushes accompanies a scene of men walking through hedge rows looking for VC; realistic explosion sounds are layered over images of bombs going off add verisimilitude to the stories. At other times, the filmmakers show restraint, as when they use spooky night video of large, tropical leaves waving in wind and rain as a narrator tells of hearing the agonizing cries of dying men. No such sounds are layered into the sound mix. It’s left to the imagination. In a scene of ARVN corpses, we hear the faint, almost subliminal, buzz of flies. Over the litany of LBJ’s confusion and bad judgments and images of LBJ and McNamara slouching and grimacing in their swivel chairs, we hear strains of Dylan’s “Eve of Destruction.” Then, it’s the NVA build-up in the South and Mick Jagger singing, “Don’t play with me/ ‘cause you’re playin’ with fire”. Of course, sixties rock ‘n roll classics have always been associated with the absurdity of Vietnam. Sometimes, the editing is strange, or playful. Karl Marlantes, a Vietnam combat veteran and author of the novel Mattehorn, gets featured treatment in the film. Commenting on the lying that so characterizes the Vietnam War as top-down history, he says: “It’s like living in a family with an alcoholic father. … You know, shh, we don’t talk about that.” When Marlantes says this, we cut to a shot of an anonymous, very young GI on the ground, looking back; he seems to be hugging the earth protecting himself from something, maybe a firefight or a mortar attack. The cut to the kid is at the precise moment Marlantes says, “… shh, we don’t talk about that.” It feels a bit jarring and cute. In the film’s introduction, we get a long segment where the iconic images and film of Vietnam (the napalmed naked girl, the shooting-in-the-head of a VC man on the streets during Tet, Hueys shoved over the side of an aircraft carrier, etc) are run backwards. It goes on for a long while. As visual metaphor suggesting the erasure of iconic stereotypes, it’s a call for fresh eyes, ears and mind. To get beyond the “dissonance” Burns and Novick speak of, I liked that they were willing to do such an unconventional thing.

Sometimes, the editing is strange, or playful. Karl Marlantes, a Vietnam combat veteran and author of the novel Mattehorn, gets featured treatment in the film. Commenting on the lying that so characterizes the Vietnam War as top-down history, he says: “It’s like living in a family with an alcoholic father … you know, shh, we don’t talk about that.” When Marlantes says this, we cut to a shot of an anonymous, very young GI on the ground, looking back; he seems to be hugging the earth protecting himself from something, maybe a firefight or a mortar attack. The cut to the kid is at the precise moment Marlantes says, “…shh, we don’t talk about that.” It feels a bit corny, like the fourth wall breaking in or something. In a scene of ARVN corpses, we hear the faint, almost subliminal, buzz of flies. Over the litany of LBJ’s confusion and bad judgments and images of LBJ and McNamara slouching and grimacing in their swivel chairs, we hear strains of Dylan’s “Eve of Destruction.” Then, it’s the NVA build-up in the South and Mick Jagger singing, “Don’t play with me/ ‘cause you’re playin’ with fire”. Of course, sixties rock ‘n roll classics have always been associated with the absurdity of Vietnam.

In the film’s introduction, we get a long segment where the iconic images and film of Vietnam (the napalmed naked girl, the shooting-in-the-head of a VC man on the streets during Tet, Hueys shoved over the side of an aircraft carrier, etc) are run backwards. It goes on for a long while. As visual metaphor suggesting the erasure of iconic stereotypes, it’s a call for fresh eyes, ears and mind. To get beyond the “dissonance” Burns and Novick speak of. I liked that they were willing to do such a jarring and unconventional thing.

What interests me is how this “intimate” history of the war works in a kind of no-man’s land between non-fiction and fiction, between reality and fantasy — the cultural coordinates where we all live today. It’s the Age of Trump and charges of “fake news” are tossed back and forth; we’re told we’re living in a post-fact, post-truth world. You soon realize in the Burns/Novick film how stories are put together, or as Novick put it to Terry Gross about the Kent State narrative, how an editor “built the scene.” Pieces of film, video and stills that clearly do not come from the incident being recounted by a participant are edited together to create what can only be called a hybrid of non-fiction and fiction. Like a writer uses words and metaphors, the filmmakers use aural and visual material.

"There is no single truth in war." Is this true?

"There is no single truth in war." Is this true?

So is the film non-fiction? After all, the events recalled by a participant actually did happen; his memory could be faulty, but the origins of the memory are still real. Or is it fiction? The final edited story is constructed of narration and imagery from any number of sources. As a photographer, it was always clear to me a photograph never lied. How an image was represented was where the lie crept in. The drama this film is able to create out of snippets of history is amazing. But the use of imagery from many places to “build” a specific recounted story feels like fiction. As an assemblage of real images, the film is one thing; making these images work as components of a constructed cinematic narrative puts it in the realm of hybrid fiction. It’s all put to the service of Ken Burns’ trademark style: Keep the storytelling down in the weeds.

Jerry Lembcke, author of The Spitting Image, knows how myths can consume us:

“Ground-up views are susceptible, especially after 40 years, to the very myths they are supposed to belie. Memories that are 40 years old are too influenced by movies, novels, newspapers, and television — or those dreaded historians — to count for documentation. … In the hands of filmmakers, however, such accounts are too easily and too often used as a veneer to manage viewer perceptions. … In promoting healing instead of the search for truth, The Vietnam War offers misleading comforts.”

As cultural product, the Burns/Novick film is interesting because it shares something with some famous 19th century American cultural products in which issues of popularity and success face-off against issues of truth and integrity. I use Mark Twain and Huckleberry Finn to make a point. Twain was a tough, progressive-minded writer for whom popularity and monetary success were important. He wrote the first third of Huckleberry Finn and ran into writer’s block. He’d created an African slave who becomes the surrogate father for an abused child who is virtually an orphan oppressed by cloying “womenfolk.” Jim may be a “nigger” without education, but in the first third of the book he’s a man in the full sense of that word. Twain didn’t know where to go with the book, so he put it up for at least a decade, during which he established his own publishing company. He wanted to make more money on his books. When he finally took the book up again, he sent Jim down the Mississippi, instead of up the Ohio to freedom, which would have been logical. That lacked drama; plus he was not familiar with the Ohio River. Along the Mississippi, we get lots of great satire. In its final third, the book goes south, literally and figuratively. Tom Sawyer arrives and Jim is relegated to a chicken coop as a virtual Step-n-Fetchit. The book was a smash hit and, according to Hemingway, is the root of all modern American literature.

Meanwhile, Herman Melville writes Moby Dick without making concessions and narrative compromises for the sake of popularity and success. What is now considered the greatest America novel ever written was a total flop during Melville’s life; he had to work as a customs official in New York to support his family. To put the theme in more modern dress, consider Clint Eastwood’s great western The Unforgiven, a tale that seeks to debunk many of the myths of western dime novels and western movies. An aging killer somewhat redeems himself by standing up for abused whores. The man who played Dirty Harry has a masterpiece going here. Then, at the very end, pal Morgan Freeman is murdered by rotten sheriff Gene Hackman. Vengeance shall be mine. Does the tired, old killer shoot the miserable sonuvabitch in the back? No. The director calls up a B-movie thunderstorm and, now dressed as the spaghetti western Man-With-No-Name in an imposing rain slicker, our hero rides into town and guns down Hackman and a dozen other men with a six shot revolver.

The Vietnam War is a compelling assemblage of stories; watching the first five episodes certainly took me back in time 50 years. I could not get enough of it, and looked forward to the next episode. But the film does seem to go soft on some of the kinds of truth Melville would have hung in for. The fact is you can’t make something of the order of the Burns/Novick film without money; and money means influence over historic and artistic choices. The money that makes such a film possible also channels and constrains it. It’s a fundamental American reality. Everytime I see the credits touting major funding from David Koch and BankAmerica, I would think of Citizens United and feel a twinge of nausea.

It was hard to keep current politics out of my mind as I watched the film on Vietnam. I was constantly reminded of the belligerent phony currently in the White House and all the other absurdities of current Washington DC. What Donald Trump is is a brutally honest, cartoon version of everything that got us into Vietnam and kept us there — the arrogance, the dishonesty, the cruelty. That he avoided the draft makes him that much obnoxious. As Leonard Cohen sang, “Everybody knows the ship is sinking/ Everybody knows the captain lied.” These days, if they don’t already, everybody should know how morally bankrupt the driving forces that gave us Vietnam were. All this is actually in the film. One of the major themes of the first five segments is the honorable young American male under the delusions of WWII volunteering to go to Vietnam to keep the WWII legacy alive. These men are betrayed by the political classes, which includes leaders of both sides. According to the film, honor can still reside among these soldiers. This is the conceit that drives the US government’s 50th Commemoration project; the major difference is that PBS adds the betrayal theme. Personally, I don’t see my service in Vietnam as “honorable.” Any innocence, ignorance or good intentions I might have had were betrayed by my leaders, whose bidding I was doing. If the war was immoral, as I believe it was, it feels delusional to suggest my service in it could somehow be honorable. This is why so many men threw their medals back at the capitol. I should be let off the hook of any responsibility because I was young and clueless? It’s the same as the issue with cops domestically: A police officer is not culpable for killing an innocent black man because he was scared shitless? Complicity is unavoidable.

It may be impossible to do what Burns and Novick set out to do, heal the dissonances and the wounds of the Vietnam War. Veterans and citizens may end up like the two protagonists in Bernardo Bertolucci’s great five-hour epic 1900, a saga about the right and left in Italy from dawn on January 1, 1900 when two babies are born to 1976 when the film was made. In the final scene, after 76 years of struggle, the landowner’s son (Robert DeNiro) and the son of the estate’s chief peasant (Gérard Depardieu) are shown walking into the distance down a railroad track. It’s a comic scene, making it a bit hopeful. They are verbally abusing each other and beating each other with their canes.

Meanwhile, as Jan Mieszkowski says in the epigram, peace continues to be an anomaly.