I saw the masked men

Throwing truth into a well.

When I began to weep for it

I found it it everywhere.

– Claudia Lars

I was raised an atheist and remain an atheist, but I came to appreciate Jesus Christ after several trips to Honduras and El Salvador during the Reagan Wars there. In the 1950s, my father tried to go corporate in a suburb outside New York City, where he worked for a pharmaceutical company; to be politically correct, he sent me to Sunday School in the basement of a small Presbyterian church. All I recall from that brief episode was that Jesus was a fellow in sandals and a robe who loved everybody and helped poor people.

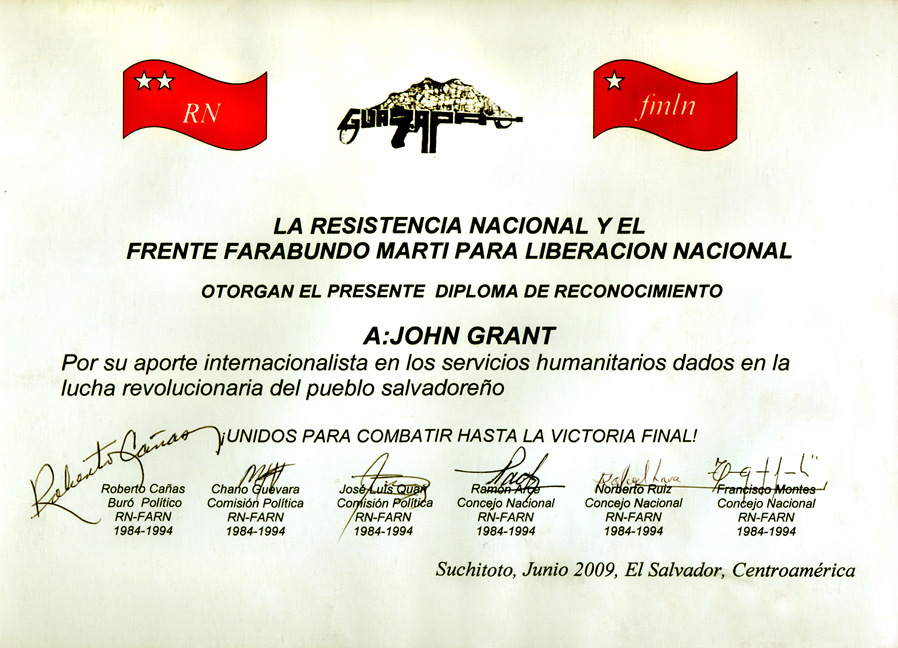

[A mother and her children overlooking the city of San Salvador]

Fast forward to the early 1980s. I ended up in Philadelphia to pursue a masters degree in journalism at Temple University. I taught myself photography in a closet darkroom. Then, I joined a junket to Central America that was deported from Honduras for opposing US intervention there. What I learned from this trip was that my government was on the wrong side of good and evil. The story was, no doubt, very complicated, but this was war where the first casualty was truth and everything becomes a matter of life and death. The fact was, the Reagan administration supported a proxy army based in Honduras that used violence and terror in an effort to overthrow the Sandinista government in Nicaragua — while it did PR at home to clean up the unsavory facts for the comfortable American mind and for the corrupt Congress of the time.

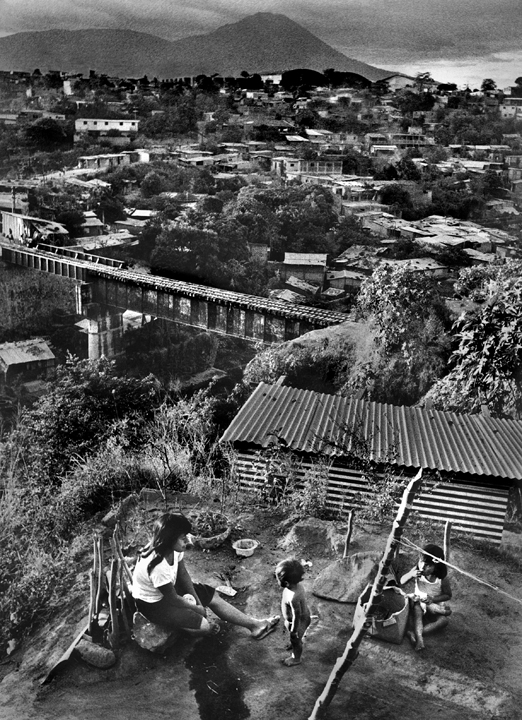

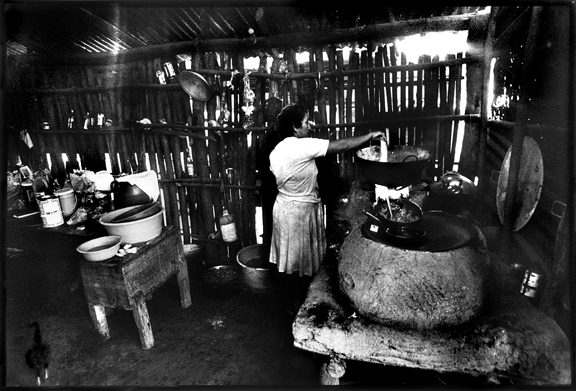

I’d never seen the kind of poverty up so close that I witnessed in Central America in the number of trips I made. In Vietnam, I’d been protected as a member of a huge military invasion/occupation force. Central Americans were trying to retain their dignity under US occupation in Honduras, or, as in El Salvador, they were fighting outright against a ruthless army and murderous paramilitary forces fully supported by my government that was winking, nodding, shifting and jiving so cynically at home anyone who wasn’t paying attention (and that included lots of people) could see nothing but a classic struggle against “communism”, a misleading label that amounted to a target for acceptable violence. This was the climate in the 1970s when Salvadoran poet Claudia Lars wrote the lines quoted above.

Honduras suffered its latest humiliation under President Obama and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. I’ll let Dana Frank, a woman who has spent many years in Honduras, tell the story from her recent book, The Long Honduran Night: Resistance, Terror, and the United States in the Aftermath of the Coup.

“On June 28, 2009, at 5:30 in the morning, the Honduran military deposed democratically elected President Jose Manuel Zelaya Rosales, in the first successful Latin American coup in over four decades. …During the weeks that followed, the Obama administration moved swiftly to recognize and then stabilize the post-coup regime. In the face of an international outcry against the coup, the United States helped the perpetrators play out the clock until a previously scheduled election arrived in November, then recognized the outcome of a completely illegitimate electoral process controlled by the coup leaders themselves — bringing to power a vicious and corrupt post-coup regime.”

Before the coup, it was true, Honduras had been run by corrupt oligarchs. But “the forces of complete corruption remained at bay. …The coup precipitated a rapid downward spiral that cast Hondurans into a maelstrom of repression, violence, and increasing poverty. …The murder rate shot to the world’s highest. …In response to their country’s devastation, hundreds of thousands of Hondurans fled the country and traveled north in the worst of dangerous circumstances.”

The fact is, US complicity with the coup, whether before or after the fact, made a rotten situation much worse.

It was in the homes of peasants that I met the same kindly Jesus I’d encountered 30 years earlier in Sunday School, a humble, loving human being. Of all people, the tough-guy novelist Norman Mailer wrote a 1997 novel titled The Gospel According to the Son. Jesus is the first-person narrator who says this in the closing lines of the book:

“[W]ho but Satan would wish to tell us that our way should be easy? For love is not the sure path that will take us to our good end, but is instead the reward we receive at the end of the hard road that is our life and the days of our life. So I think often of the hope that is hidden in the faces of the poor. Then from the depth of my sorrow wells up an immutable compassion, and I find the will to live again and rejoice.”

Mailer begins his audacious “gospel” by having his Jesus tell us the gospel of Mark “has much exaggeration,” while those of Matthew, Luke and John “gave me words I never uttered and described me as gentle when I was pale with rage.” Mailer made a career out of being audacious, so why not an equally fictional gospel for our age?

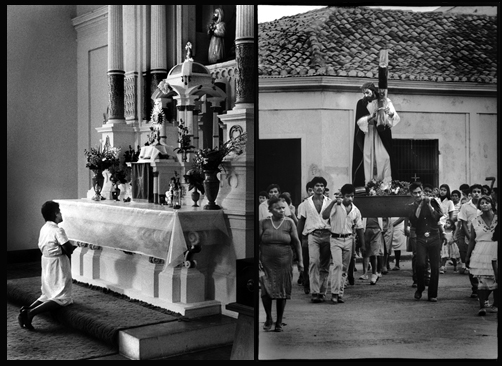

The people I met in El Salvador felt a strong loyalty to the Jesus of Liberation Theology; this is a Jesus who stands in direct opposition to the imperial Jesus familiar to followers of the American fundamentalist right. In a tiny, densely-populated nation like El Salvador, a similar entrenched rightist theology is ingrained in the formal, conservative church of large, ornate cathedrals with priests wearing crinkly, golden vestments and fancy hats; this is a church powerfully linked with the most wealthy and conservative elements of society. In El Salvador, it was “the 14 families,” which refers to the oligarchy that controlled El Salvador during the 19th and 20th centuries; it also may have something to do with the 14 regional “departments” the nation is broken into. This oligarchy has been historically closely aligned with the United States and consistently oppressed the poor, taking the most arable land by force and using violence to get its way. Priests told the peasantry that life was about suffering, and if one lived a good, obedient life, one would go to Heaven where there would be no more suffering. Asking for a better life while one was still alive was frowned upon, and if one did raise one’s voice, well, there were always the cruel men with guns — those “masked men throwing truth into a well” Lars wrote of. According to Wikipedia, “Eight business conglomerates now dominate economic life in El Salvador.” They are, of course, linked with powerful forces in North America.

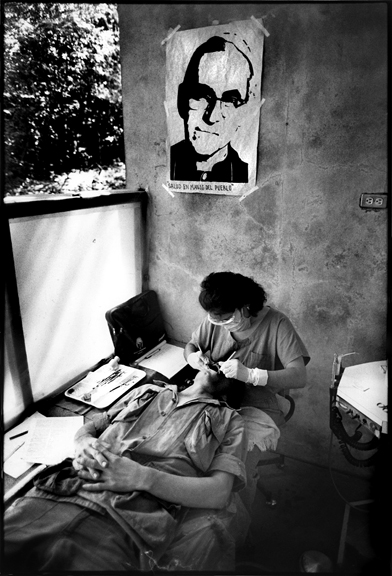

[Twelve-year-old Edwin, left, poses in the Chalatenango village of San Jose Las Flores, as he requested, “con fusil,” after visiting the grave of a friend recently beaten to death by Salvadoran soldiers. At right, an FMLN soldier on the Guazapa volcano outside of San Salvador. Below, an FMLN dentist’s office on the Guazapa volcano. Note the photo of the martyred Archbishop Oscar Romero, an image seen throughout the rebel zones.]

As I traveled around El Salvador into the rebel zones of Chalatenango, San Vicente and on the Guazapa volcano, I ran into guerrillas and “delegates of the word,” un-ordained peasants who told the story of the Liberation Theology Jesus, who preached one could ask for change now — in this life. To back up their spiritual message they had the FMLN, the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front, established in 1980 seven months following the assassination of Archbishop Oscar Romero, a conservative, bookish priest promoted to that high office by a conservative church that figured he’d be a safe bet. He backfired. This quiet, unassuming priest became attuned to the compassionate Christ and began to listen to the poor and to speak out against rightist violence. To young men shanghaied into the military and used to kill their own people, he spoke out publicly and eloquently. While giving mass to a group of nuns in a small chapel, Romero was shot through the front door by a man with a rifle in the passenger seat of a car.

[Top two photos: Jesuit writer Ignacio Ellacuria speaks to a large crowd in a square in San Salvador in March 1989. Bottom left, Lutheran Bishop Medardo Gomez speaks at the same rally sponsored by The Permanent Committee For a National Debate. Bottom right: Roberto D’Aubuisson speaks at an ARENA rally in the very same square the next day. A notorious leader of death squads, D’Aubuisson was the founder of the ARENA Party. Here, he was speaking at a rally for an ARENA candidate for president. Philosophy and theology professor Ellacuria was one of the six Jesuits murdered by Salvadoran soldiers along with their housekeepers in November, eight months after these photos were taken. The back of Ellacuria’s head was reportedly blown away, some say as a terroristic gesture focused on his intellectual work in philosophy and theology. As for Bishop Medardo Gomez, I had papusas (a stuffed tortilla delicacy) and beer at his house, where he told us gringos about being captured by thugs in 1983 and being roughed up. I’ll never forget his message: Contrary to the instinct to hide, Gomez said it was important to go public and speak out forcefully, which he did and was doing with us. In the end, however, after the six Jesuits were so blatantly and openly murdered, he fled into exile in the US.]

Violence in Central America is foundational, reaching back to the days of the Conquistadores, adventurers who came looking for gold. All Salvadorans know about La Matanza, or The Slaughter. In 1931 Maximiliano Hernández Martínez took power in a coup; the following year, among others, Farabundo Marti led a peasant revolt. The reaction was horrific: within a short time estimates have it that up to 40,000 peasants and political opponents were murdered, imprisoned or exiled. Because of La Matanza, Salvadoran peasants no longer wear native costumes, since that fashion was how victims were identified to be killed. Salvadoran peasants abided until another wave of opposition to oligarchic outrages took root in the 1970s. A grassroots military force arose and was named for Farabundo Marti. Liberation Theology took on the oppression of the Roman Catholic Church. Solidarity with North Americans was established, leading many North Americans like myself to trek south for answers person-to-person and on the ground, fed up with relying on the tired old Cold War narrative that struggling, even angry, peasants were communists to be crushed like vermin. As a Marine Vietnam vet I knew loved to say: “Kill a Commie for Mommie.”

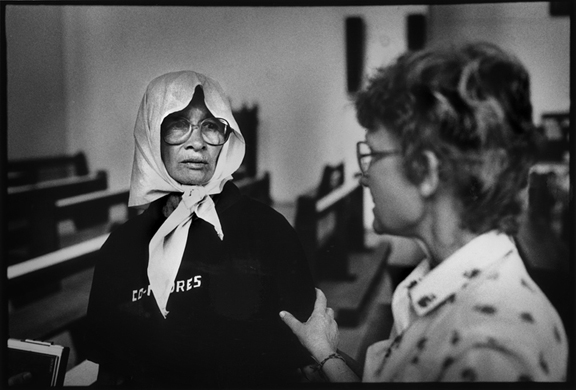

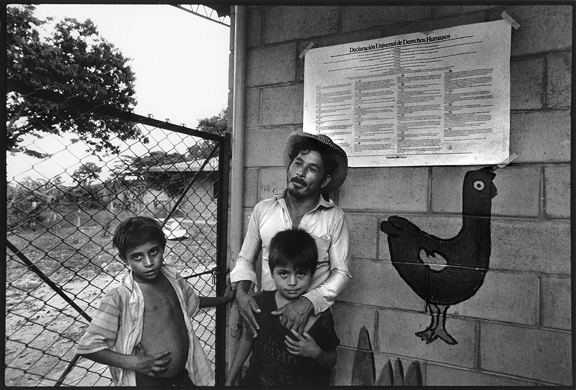

[A woman who told our group of searching for her missing daughter and finding her body partially skinned in what was a common body dump. Having such a privileged, North American upbringing, I began to ask myself: How can people do this kind of thing to each other? How can my government effectively support it? I’m still asking these questions. Below, a father near the relocation village of Santa Marta with his two sons in front of a poster listing the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.]

Concerning Liberation Theology, Gustavo Gutierrez from Peru writes in We Drink From Our Own Wells that “Liberation is an all embracing process that leaves no dimension of human life untouched, because when all is said and done it expresses the saving action of God in history.” One might say Gutierrez is exploiting the idea of God to advance the interests of the poor in Latin America. And they’d be right, in my atheist mind. Writers on the right like Dinesh D’Souza and John Hagee feel the Liberation Theology God is a false God, while they’re certain God is really on the side of Imperialism and Capitalism. Napolean reportedly said: “God is on the side of the force with the most logistics.” The point for me is when we get to the level of oppression and killing as a means of solving the human problems of fairness and justice, well, I wouldn’t deny Latin American peasantry the right to manifest their natural human spiritual yearnings any way they like.

Here’s Gutierrez again: Liberation Theology “is based on the conviction that the poverty being experienced in Latin America … is death-dealing and denies the basic human right to existence and the reign of life.” (Italics in original.)

In this i-phone, social media age, the struggle between peasant dignity and imperial power that has played out so cruelly in Central America has now come north to meet us at the long US border with Mexico. It has become a battle zone. US involvement in Central America’s problems is so historic and so profound that we hear virtually nothing about it. This fact must be related to Joseph Goebbel’s idea of “the big lie.” If assumptions become accepted in a culture like we accept breathing or the weather, then one can say (or not say) virtually anything as long as it’s in alignment with the cultural assumptions. Our media is transfixed by if-it-bleeds-it-leads, celebrity and ball-score political coverage and, while it covers the excesses and horrors on the border, it fails miserably when it comes to covering the background to the border mess.

We live in a world overwhelmed by corruption, secrecy and the sophisticated use of violence. As in the dark ages, religion becomes a haven of certainty. Globalization is taking over the globe at the same time weakened nation states are overcompensating with fervent nationalism. In this situation, the plight of poor Central Americans is that of being between a rock and hard place. Oligarchs in places like El Salvador are part of the same class as those with wealth in the United States; artificial intelligence and robotics loom over the functions of production. The peasantry in Central America are part of a future world where working people will become superfluous. Political movements like Make America Great Again and rightist efforts to oppress the immigration of those caught between the rocks of Central America and the hard places along the US Border only want to deal with the “winners” in this cruel distribution of humanity.

The newly elected president of El Salvador is an interesting wrinkle in the Central America US Border Blues. He’s not connected to either the right-wing ARENA Party or the left-leaning FMLN Party. President Nayib Bukele recently did something very unusual: He took responsibility. “People don’t flee their homes because they want to,” he said in English. “They flee their homes because they feel they have to.” Then he said the unthinkable: “It is our fault. … We can say President Trump’s policies are wrong. We can say Mexico’s policies are wrong. But what about our blame?” He acknowledged it was economic duress and insecurity that drove people north. “They feel it is safer to cross a desert, three frontiers, and all of the things that may happen on the road to the United States because they feel that’s more secure than living here.” As for the Trump administration, he said: “I think they are approaching this in the wrong way. History has shown that this will not stop migration.” Like Pete Buttigieg here in the US, Bukele is 37-years-old. Can his youthful honesty and freshness move this issue toward sanity? Does he have the backbone necessary? Or will he be chewed up by the violence of Salvadoran and US politics?

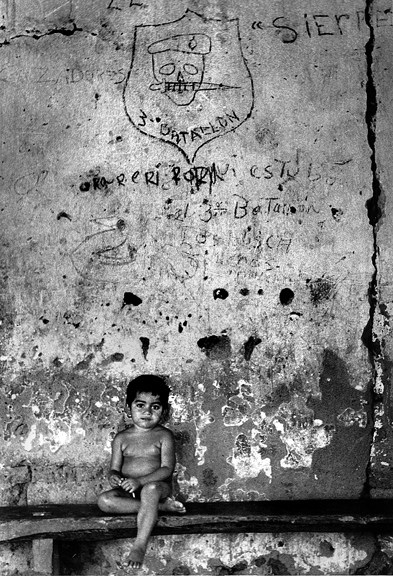

[A child in San Jose Las Flores, a re-populated Chalatenango village of refugees returning from their flight into Honduras. The graffiti was left by the 3rd Battalion of the Salvadoran army when they passed through.]

The cruelty of the Trump administration at the US border is hardly a new phenomenon. It’s the same old story, only more desperate. Nothing positive can ever be done unless and until the history of US involvement with Central America is honestly brought into the discussion.

“Satan would wish to tell us that our way should be easy,” Norman Mailer’s Jesus tells us. Nothing is as “easy” as the Tweet-driven violent approach advocated by Donald Trump: Lock ’em up. Be brutal, and they’ll go home. Novelist Mailer concludes that won’t work; the only possible answer is Love. Hard-earned Love: Something the much-oppressed people of Central America know well and which I profoundly witnessed back in the 1980s.

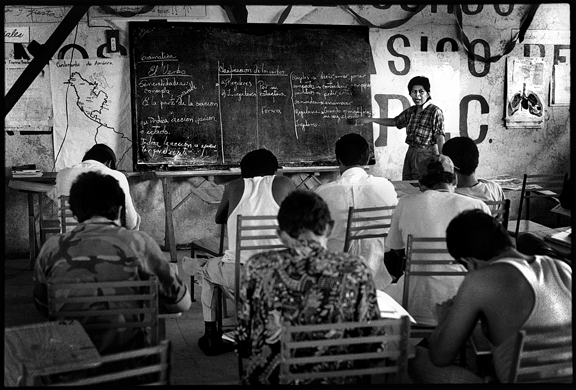

[Above, a grammar lesson in the rebel zone on the Guazapa volcano, and, below, residents of San Jose Las Flores in Chalatenango.]

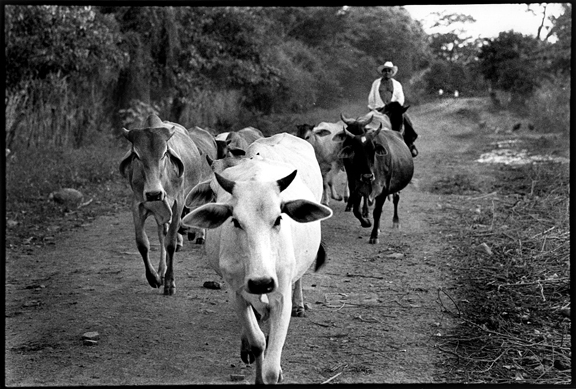

[All the photos, above, are by the author and were taken in the late 1980s in El Salvador. Below, the award given to me June 2009 in Suchitoto, Chalatenango, at a lunch of veteran FMLN fighters. As a member of Veterans For Peace, I had spoken to a gathering of FMLN veterans the day before in San Salvador. I was in El Salvador for the inauguration of Mauricio Funes, the first FMLN Party candidate elected president of El Salvador. While I don’t really feel I deserve such an award given “For his internationalist contribution in humanitarian service to the revolutionary struggle of the Salvadoran people,” that said, I’m greatly honored to have been given it.]