I never met Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., or attended a march or rally where I could hear him speak, but on the evening of April 4, 1968, an hour or so after he was assassinated, I was in a jail cell in Concord, Mass. writing a freshman paper about King, Gandhi and Thoreau, and their shared ideas about the power of non-violent political protest.

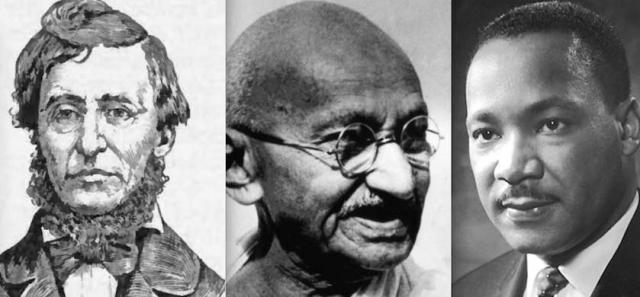

It had all started out when I found myself with a classic case of writer’s block, unable to get started on an end-of-the-term paper for my philosophy class at Wesleyan University in Connecticut. The topic I had chosen was tracing Martin Luther King’s political roots back through the thought and practice of Indian independence leader Mohandas Gandhi and philosopher and anti-war protester Henry David Thoreau.

Stuck for words, I decided on a whim or in desperation on the morning of my birthday to hitchhike, for inspiration, up to Concord and to Walden Pond, where Thoreau famously had built a small cabin in which he was living when he wrote Walden, and also his famous and hugely influential essay On Civil Disobedience — the latter work by way of explaining his decision to refuse to pay his taxes because of what he considered the United States’ illegal war against Mexico.

The US was, of course, at the time of my little pilgrimage, waging a similarly illegal and far more vicious and destructive war on the people of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia — a war that I had already decided a year earlier that I would not participate in.

I had, the prior October, gone down to Washington DC to join the historic Mobe March on the Pentagon, and had been arrested on the Mall of that huge building dedicated to war, spending several days locked up in the federal prison at Occoquan, Va. on misdemeanor charge of “trespassing” on federal property and, because I had gone limp and forced the marshals to carry me, “resisting arrest” (I got a five-day suspended sentence and was fined $50). I probably would not have decided to remain sitting, pressed right up against the feet of armed federal troops, especially when they started grabbing legs, pulling people through the line and beating and arresting them, but the beautiful and courageous young highschool girl I had met and stayed with on the march earlier and through the night on the mall, was yanked through and carried off as I was mulling that question over. I decided then and there that I had to stay and get busted too. (We ended up riding to the prison in the same van.)

I had made a firm decision while still in high school that I would not allow myself to be drafted, and was waiting to be called up, when I would have to face the consequences of that refusal, having decided not to file for a student deferment while in college, which I decided was unfair to those young men who were not able to go to college to escape the war. (My being called up became a certainty later when the draft lottery was established and my number came up as 81, but that’s another story.)

One of the big influences in my decision, shortly after my 18th birthday in 1967, to go to the local draft board and register for the Selective Service, at the same time telling the woman staffing that office that I would not allow myself to be drafted, was reading about King’s momentous address at Riverside Church in New York, made on April 4 of that year. In that address he clearly, for the first time, linked that criminal war and its violent genocidal repression of the Vietnamese people to the brutal racism and class struggle at home in the US. (I urge all those reading this piece to take the time to read his remarkable, revelatory, heartfelt and sadly prophetic address in full or, better yet, listen to him deliver it himself here.) It was a lot to take in for an 18-year-old high school kid, but King made it crystal clear that all these things were connected, and that making real change meant tackling them all, with a broad coalition. (Many, myself included, believe that it was that speech, so dangerous to the Establishment power structure, that sealed King’s fate a year to the day later, with a bullet whose timing seemed ominously designed to send exactly that message.)

My short time spent in a dormitory cell at Occoquan six months later, while short, was probably the most important time in all my four years of undergraduate college study. Locked up with me in that cell were hardened veterans of political action, in particular the civil rights struggle against segregation and for the right of African Americans to vote in the South. These veterans of the struggle, along with other veteran leftists caught up along with me by the Federal Marshalls guarding the entrance to the Pentagon, became the impromptu adjunct faculty of a makeshift “people’s university” who opened my eyes to the wider issues of US imperialism, racism and the corrosive, destructive role of capitalism in America. They helped me to refine what King had said a year earlier.

It was with all that swirling in my mind, and with the knowledge that the war in Indochina had become even more serious and violent following the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Tet Offensive earlier that year and President Lyndon Johnson’s subsequent surprise announcement wees earlier that he would not seek re-election that year, that I headed out on the road for Concord on the morning of April 4, 1968. It at least appeared (wrongly it turns out), that the tide had turned and that perhaps the anti-war movement of which I was a tiny part was helping to end the war, and perhaps might also eventually lead to positive changes in the US, too.

At any rate, at the time King was slain, I was out in the early evening, under darkening skies that threatened rain, making my way by thumb along secondary roads in Massachusetts trying to get to Concord and to my destination, Walden Pond. I didn’t know that the main subject of my paper, yet to be written, had already been shot and was being rushed to the hospital to be pronounced dead as I walked the last mile or so to the little park that contains the pond.

Reaching the park at dusk, I wandered around until I found the marked spot, a slight depression in the ground, where Thoreau’s cabin, long since rotted away, had been. Figuring it was where I should bed down, I spread out my much too light sleeping bag and crawled in, just clouds began to release a cold drizzle a light rain. I pulled the bag over my head, took out my flashlight, opened my notebook, and pondered how to start the paper.

Before I could write a word though, a gruff voice rang out. “What the hell do you think you’re doing?” I heard. Sticking my head out of the bag, I found myself looking up at a large police officer who was shining his flashlight down at me.

I explained to him that I was a college student and that I had come to Walden Pond to write a paper on Thoreau’s and Gandhi’s influences on Martin Luther King. He replied, shockingly, “Yeah, well they just shot him. He’s dead!”

I was dumbstruck! How could this be? I asked for more information and the cop just said, “Someone shot him in Memphis.”

Then he said, “Come on. You have to leave the park. It’s closed after sunset.” Then, a little more kindly, he added, “Anyhow, you can’t sleep here. It’s raining.”

I said I didn’t have anywhere to go, and he said, “Well, you could sleep in the jail, but I’d have to arrest you to put you in a cell. You’d be charged with vagrancy, but in the morning we can rip up the ticket and let you go.”

It sounded like a good deal to me, so I followed him to his squad car and we rode to the jail. While it wasn’t the same Concord police station that would have been there in Thoreau’s time, I realized that the jail I was being brought to was the direct linear descendant of the jail in which Thoreau had spent a night for his tax refusal. That is where Thoreau was famously visited by his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson, who reportedly said, “Henry, I’m sorry to find you here,” to which Thoreau replied, “Mr. Emerson, why are you not here?”

My own night in the cell was largely uneventful, except for a disturbing snippet of conversation between two of the cops on the night shift, whom I overheard discussing the King assassination.

“That’s King’s widow on the radio, talking about her husband,” said one cop.

“Yeah, they finally killed that nigger,” said the other.

Clearly, I thought to myself, this country has a lo-o-o-ong way to go.

It still does.

That night, I sat in my cell on a hard bench that served as the bed, locked inside in accordance with jail rules, and hungrily ate the peanut-butter and white bread sandwiches offered to me by my racist jailers, while I wrote my paper which, at that point, came easily to me.

Martin Luther King, Jr. was dead, but the movement to create a peaceful society and a peaceful world where people are not oppressed or exploited, and where every child of every race and nationality can grow to her or his full potential continues as his legacy, half a century later.

No one, certainly including Dr. King, ever said it would be easy.