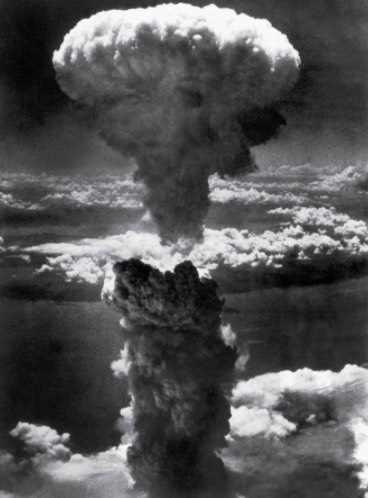

75 years ago, just before dawn on July 16, 1945, a cataclysmic explosion brighter than the still unseen sun hook the New Mexico desert as scientists from the top-secret Manhattan Project tested their nightmarish creation: the first atom bomb dubbed “the Gadget” by its inventors (the test was called “Trinity.”)

This birth of the Nuclear Age was quickly followed a few weeks later in a much more horrific fashion, first on August 6 by the dropping of a U-235 atom bomb on Hiroshima, a non-military city of 225,000, and then, three days after that on Aug. 9, by the dropping of a somewhat more powerful Plutonium atom bomb on Nagasaki, another non-military city of 195,000. The resulting slaughter of some 200,000 mostly civilian Japanese men, women and children as a result of these two explosions naturally has leds to talk of the horrors of those weapons and to discussions about whether they should have been used on Japan instead of being demonstrated for Japan’s leaders on an uninhabited target.

What goes unmentioned, however, as we mark each important annual anniversary of these horrifying events — the initial Trinity test in Alamogordo, the “Little Boy” bombing of Hiroshima and the “Fat Man” plutonium bombing of Nagasaki — is that, incredibly, in a world where today nine nations possess a total of nearly 14,000 nuclear weapons, while hundreds of bombs have been exploded, mostly underground, in tests of new designs, not one nuclear weapon has been used in war to kill human beings since the bombing of Nagasaki on August 9, 1945.

And that’s not all. Over those same 75 years, despite seven and a half decades of intense hostility and rivalry, as well as some major proxy wars between great powers like the US and USSR, or the US and China, no two superpower nations have gone to war against each other. (Neither have any smaller nuclear powers, like India and Pakistan or India and China, even in the case of small border skirmishes, allowed things to excalate to going nuclear.)

The reason for this phenomenal and almost incomprehensible absence of catastrophic conflict of the type so common throughout human history given the existence of such weapons of unimaginable power, is the same in both cases: No country dares to risk the use a nuclear weapon because of the fear it could lead other nuclear nations use theirs, and no major power dares to go to war against another major power because it is obvious that any war between two such nations would very quickly go nuclear.

Things could have gone very differently, however, following the dawn of the nuclear age.

At the end of WWII, the US was the world’s unchallenged superpower. It had emerged from war with its industrial base undamaged while Europe, the Soviet Union, Japan and much of China and were all smoking ruins, their dead numbering in the tens of millions and their industrial bases leveled. The US also had a monopoly on a new super weapon — the atom bomb — a weapon capable of vaporizing a city in a second. As well, this country had made certain that before the war ended, it had demonstrated to the world that it had no moral compunction going forward about using its terrible new weapon of mass destruction on those who might cross it.

Some important scientists involved in the creation of the bomb urged the sharing of its construction secrets with America’s crucial ally in the war against the Axis powers, the Soviet Union. These scientists, many of them Nobel-winning physicists like Nils Bohr and Enrico Fermi, said negotiations should begin immediately at that point to eliminate nuclear weapons for all time, just as germ and chemical weapons had already been banned (successfully as the history of WWII and their virtual non-use showed — though the US, significantly, did illegally use germ warfare against North Korea and Cuba).

But rabidly anti-Communist military and civilian leaders in Washington balked at the idea of sharing the bombs’ secrets with the USSR . In fact, after a visit Bohr, who pleaded with him to bring the Russians into the bomb project, President Roosevelt reportedly had the FBI monitor him. Roosevelt reportedly even considered barring home from leaving the US to return to his native Sweden. The Truman administration later considered deporting Leo Szilard, another Manhattan Project “peacenik” proponent of sharing the bomb. and after Manhattan Project Chief Scientist Robert Oppenheimer proposed to Truman the sharing of the bomb with the Russians, his top-secret security clearance was revoked.

Instead of sharing the bomb with the USSR, which on should remember was America’s ally in World War II, and then working for its being banned, the US began producing dozens and eventually hundreds of Nagasaki-sized atom bombs, moving quickly from hand-made devices to mass-produced ones. The US also immediately started pursuing the research and development of a vastly more powerful bomb — the thermonuclear Hydrogen bomb — a weapon that theoretically has no limits to how great its destructive power could be. (A one-megaton bomb typical of some of the larger warheads in the US arsenal today is 30 times as powerful as the bomb dropped on Nagasaki and both the USSR and the US developed vastly larger ones than that.)

Why this obsession with creating a stockpile of atomic bombs big enough to destroy not just a country but the whole planet at such a time as the end of WWII? The war was over and American scientists and intelligence analysts were predicting that the war-ravaged Soviet Union would need years and perhaps a decade for its physicists and engineers to produce its own bomb. Yet the US was going full tilt building an explosive arsenal that quickly dwarfed all the explosives used in the last two world wars combined. (It’s almost as if Dick Cheney and his Project for a New American Century were already in power back in the mid- to late ’40s!)

What was the purpose of building so many bombs? One hint comes from the fact that the US also, right after the war, began mass producing hundreds of the B-29 Super Fortress — planes like the Enola Gay that delivered the first atomic bomb to Hiroshima — and even de-mothballing and refurbishing hundreds that had been built and declared surplussed right at the war’s end. At that time, only the B-29 could only carry a plutonium or uranium bomb for any significant distance, though it already had that plane in decent numbers at the war’s end, the US began producing several thousand of them in peacetime.

Why?

The answer, according to a 1987 book, To Win a Nuclear War, authored by nuclear physicists Michio Kaku and Daniel Axelrod, is that the US was contemplating launching a devastating nuclear first strike blitz on the Soviet Union as soon as it could build and deliver the 300 nuclear bombs that Kaku and Axelrod document that Pentagon strategists were claiming would be needed to destroy the Soviet Union as an industrial society and wipe out its powerful Red Army as well. The idea was to also eliminate any possibility of the USSR responding by sweeping over war-ravaged western Europe. The B-29 was at the time the only plane the US had which could deliver the atomic bombs.

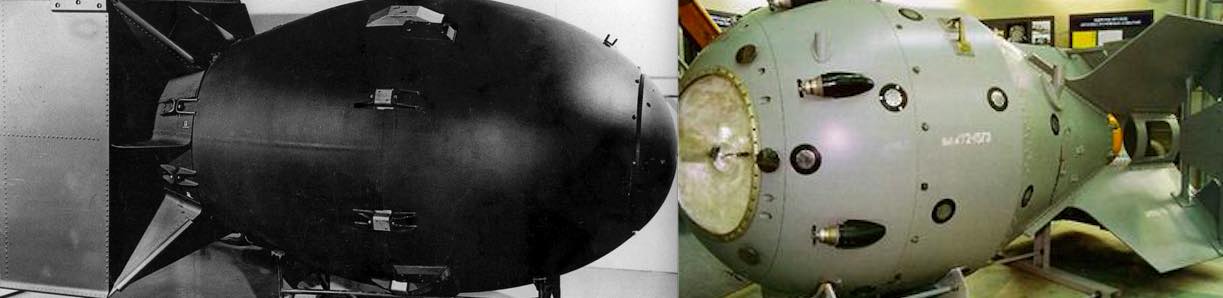

This genocidal nightmare, which Pentagon strategists estimated could kill upwards of 30 million Soviet citizens, was being actively planned by Truman and the Pentagon’s nuclear madmen, but fortunately never took place because the initial slow pace of constructing the bombs meant that the 300 weapons and the planes to deliver them would not, to a frustrated Truman’s annoyance, be ready until early 1950. Meanwhile, Russia’s first atomic bomb, a plutonium device that was a virtual carbon copy of the “Fat Man” bomb dropped on Nagasaki (see images below), was successfully exploded on August 29, 1949, in a test that caught the US by complete surprise. At that point the idea of a deadly first strike was deferred indefinitely) by Truman and Pentagon strategists.

In its place a new era of Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD) had arrived, and according to Kaku and Axelrod, just in time.

For that bit of good fortune, I suggest, we have to thank the spies who, for whatever their individual motives, successfully obtained and delivered the secrets of the atomic bomb and its construction to the scientists in the Soviet Union who were struggling, with limited success, to quickly come up with their own atomic bomb.

To most Americans, those spies, especially the US citizens among them like Julius Rosenberg and notably Ted Hall, the youngest scientist at the Manhattan Project, hired out of Harvard as a junior physics major at 18, were modern day Benedict Arnolds, only far worse.

The truth is quite different.

Hall, who was never caught, and who was not recruited by Soviet agents to be a spy but rather volunteered plans for the plutonium bomb on his own initiative after searching for and finally locating a Soviet agent, and Klaus Fuchs, a young German Communist physicist working initially the British part of the Manhattan Project, both delivered, independently of, and unknown to each other, critical plans for the US plutonium bomb to Moscow. Their information looked at objectively almost certainly prevented the US from launching a nuclear holocaust on the people of the Soviet Union.

By decisively helping the USSR develop and test its own bomb quickly by mid-1949, just months before the US would attain a target stockpile of 300 bombs, they forced the Pentagon and the Truman administration to have to contemplate the unacceptable risk of retaliation. Had the Soviets taken much longer to create their own atomic bomb, the US would have almost certainly gone through with its criminal plans, which would have dwarfed Hitler’s slaughter of the six million Jewish and Roma people.

Hall, in public statements made in the mid-1990s after de-encrypted Soviet spy codes became public and his name was identified in them, explained publicly that he had acted to share information about the bomb because he felt that the US, coming out of WWII with a nuclear monopoly, would have been a danger to not just the Soviet Union, but to the entire world. (The Russian bomb exploded in August, 1949 was a virtual carbon copy of the Nagasaki plutonium bomb Hall had worked on in his two years at Los Alamos, and key Russian scientists who were working on developing a Soviet bomb have stated that the combined information provided by Hall and Fuchs saved them months and years of work and dead-end research.)

More specifically, while Fuchs provided the Soviets with far more information, including plans for details on methods for separating the scarce fissionable U-235 isotope from ordinary radioactive U-2338, and for the successful implosion of a core of difficult to handle plutonium, Soviet intelligence was suspicious about his reliability as a source, wondering how a young German Communist Party member had been able to both gain British citizenship, and to be allowed to work on the top secret atom bomb project. They were all the more suspicious in 1944 when he was transferred from the UK to Los Alamos and they lost touch with him for a time. It was just at that point that Ted Hall literally walked into the door or a Soviet NKGB agent and handed over his plans for the implosion device. When those plans were sent by diplomatic pouch to Moscow, and were seen to match what Fuchs had provided, those suspicions were erased, and Soviet scientists were able to decide to drop their halting efforts to obtain enough U-235 from their scarce supply of Uranium for a bomb, and to devote all efforts and resources towards developing a Plutonium bomb.

Looking back to the US decision to use its first nuclear weapon not as a demonstration on an empty island or military base, but on two undefended civilian cities, and to catastrophic US carpet bombings using non-nuclear bombs, of North Korea and later Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, it’s hard disagree with Hall’s concern about a US with a monopoly on the atom bomb. His concern about US nuclear intentions has been further borne out by how close the US came to using its nuclear arsenal in crisis after crisis during the late ’40s and early ‘50s — against China and North Korea during the Korean War, in support of the French expeditionary force trapped at Dien Bien Phu, by JFK in the 1961 in the Berlin crisis, in the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. and later when US Marines were trapped by Vietnamese troops in Khe Sanh. Each time, it was fear of the Soviets responding with their own bomb that saved the day and largely kept American bombs on the ground (in the Khe San case in 1968 atom bombs were actually delivered close to the Indochina front, but President Johnson called a halt to the military’s plans when he learned about them).

The truth is, if the Soviets had not had their own bomb during any of the above listed crises, it is hard to imagine that the US, with a monopoly on the bomb, would not have used it to full advantage. If we’re honest, The MAD reality that resulted from the successful exploits of Russia’s Los Alamos spies proved to be a lifesaver for tens or perhaps hundreds of millions of people around the globe.

Americans may (and should!) decry the hundreds of billions of dollars (trillions in today’s dollars) that have been poured into a massively wasteful arms race with the Soviet Union and later Russia and China — money that could have done incalculable good if spent on schools, health care, environmental issues etc. — but must also consider what the alternative would have been to Cold War and MAD. With MAD (and considerable good luck!) we have had no world wars, and no nuclear bombs dropped on human beings. Without it, with the US having a monopoly on the bomb for perhaps as long as a decade or more following WWII, this country would almost certainly, on the evidence of its non-nuclear behavior, have nuked cities all over the world, almost certainly destroying the Soviet Union and perhaps China too, entirely. Today, the US would then be known as the ultimate genocidal monster of history, rather than having Germany left wearing that eternal badge of shame.

In reconsidering the work of Soviet atomic spies and in particular Fuchs and Hall, Americans also need to know the truth about the goal of the Manhattan Project. While the push to develop the bomb began with a letter from Albert Einstein to Roosevelt warning that the Germans might develop such a weapon, by the time the program got underway, it was clear that the real target was America’s Ally in the fight against the Nazis: The USSR.

Without we must urgently work to ban nuclear weapons and war. Such weapons are incomparably evil and if the world agrees that germ warfare and poison gas weapons should not exist, certainly nuclear weapons a million times worse should not! But we should nonetheless, as we look back at the grim 75th anniversary of those three first nuclear bombs exploded by the US, admit a debt of gratitude to those spies at Los Alamos who kept the US from committing an atrocity that humanity would have never forgiven, and for giving us all this amazing three-quarters of a century of no nuclear or world war.

Dave Lindorff is a 2019 winner of an “Izzy” Award for Outstanding Independent Journalism from the Park Center for Independent Media. He is a founder of the collectively owned journalism site ThisCantBeHappening.net