(This article is Part III of journalist Ridenour’s political autobiography, Solidarity and Resistance: 50 Years With Che. Click here for Part I and here for Part II)

Grethe Porsgaard and I fell in love, in 1979. She was from Denmark and vacationing in Los Angeles. I traveled to her homeland, in 1980, where we married. At my behest, we made a go of it in her country. A major factor in that decision was that my former wife had taken our children, whose upbringing we had been sharing, from me, and had turned them against me. It would have been a negative way to begin a new love life living close to that madness. Although Grethe and I ended our marriage after several years, we remain friends.

In the first years in Denmark, I worked at odd jobs and wrote freelance, while also participating in Central America solidarity activities. In the course of that work, I met an El Salvadoran guerrilla leader in Copenhagen while he was on tour for the FMLN. We agreed that I would travel clandestinely to El Salvador where I would accompany guerrillas in the countryside, with the goal of writing a book.

This project led to my first visit to Cuba, in the autumn of 1987. My first book, Yankee Sandinistas: interviews with North Americans living & working in the new Nicaragua, had just been published by Curbstone Press in the US. At the recommendation of Cuba’s embassy personnel in Copenhagen, I offered it to Cuba’s foreign book publisher, Editorial José Martí, to publish a Spanish translation.

In a few days, the publishing house director told me that they wished to publish my book and had assigned a translator to it. Delighted, I signed a formal contract. Later, I saw Fidel hold a four-hour speech in the convention center and hung on to every word. It was true what was said about his abilities as a speaker: he was the world’s greatest orator. And what a memory he had! He could start off somewhere and go around the world describing how it was and how it is, and do so without notes or even water, and seemingly all in one long breath.

Just the year before, the government had launched a period of “Rectification of Errors and Negative Tendencies” as a response to economic and political stagnation. The leadership now realized that copying the Soviet Union’s Economic Management and Planning System for 15 years had been a mistake. Rectification was aimed at diversifying domestic production, reducing dependency on the mono-culture export of sugar, stemming market-economy tendencies, and emphasizing volunteer labor.

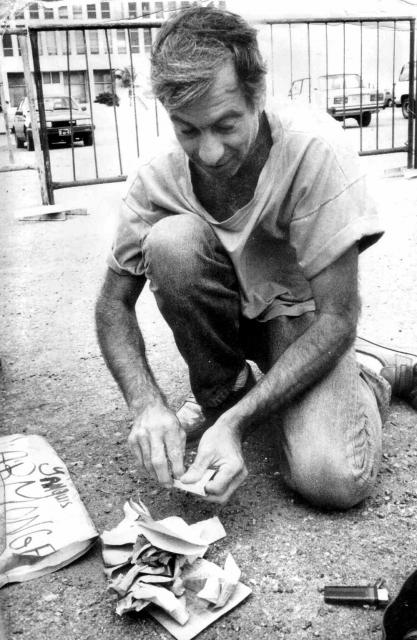

Author Ron Ridenour burns his US Passport in front of US Special Interests Section building in Havana

Author Ron Ridenour burns his US Passport in front of US Special Interests Section building in Havana