“Blows that don’t break your back make it stronger.”

– Anthony Quinn in Omar Mukhtar, Lion of the Desert

For years, I’ve been working either in the journalism realm or as an antiwar veteran activist expressing the core idea that the United States of America is an “empire,” that its militarist foreign policy is “imperialistic” and that many of our perennial and current problems are rooted in the reality that, as an imperial nation, like many empires in history, we’re overextending ourselves and destroying something that is dear to all American citizens who love this country.

When I wrote guest opinion pieces for the Philadelphia Daily News, a good-natured debate developed between me and the paper’s regular columnist, Stu Bykofsky. I don’t mean to pick on Stu, but his position was classic empire denial. He would argue we weren’t an empire because US troops didn’t look or act like Roman legions. He seemed to feel that Americans were always good and always intervened around the world to slay monsters or help the benighted peoples of the world. Unlike the Brits, we did not exploit the wogs while we played cricket and drank gin and tonics on the verandah. Of course, he’s right that the nature of empire has evolved with the times. But for me the argument was all semantics. It seems hard to claim that the United States is not an empire or that its imperial drive — with some 700 military bases around the world — has not led to a problem of overextension that plays to the detriment of US citizens at home.

The other night, I stumbled on the 1981 film epic Omar Mukhtar, Lion of the Desert. Mukhtar was a simple village teacher of the Koran in Libya who turned out to be a natural military genius; he brilliantly fought an occupying Italian army from 1911 to 1931. Italy had taken Libya from the declining Turkish empire. Once Benito Mussolini rose to power in 1922, the occupation became a powerful drive to establish “the fourth shore,” the name given to Italy’s ambitions to re-create a new Roman Empire in North Africa.

.

.

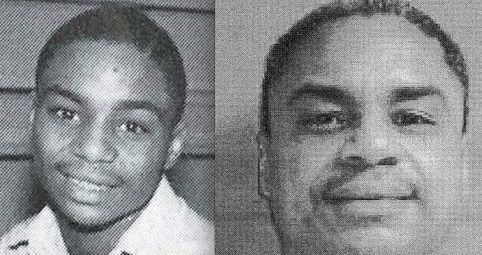

Above, General Graziani (Oliver Reed) readies his troops to brutally attack a Libyan village. The real Graziani in the inset photo. Below, Quinn as Mukhtar with the boy who ends up with his glasses; the real Mukhtar before he is hung, and his hanged body.

.

.

Anthony Quinn plays Mukhtar in the three-hour film, which to my surprise is a well written, acted and filmed cinematic gem. Like The Battle of Algiers, the film offers serious insights for a western audience. When the film was released, following the 1979 Iranian Revolution and the Iranian hostage crisis, it bombed. It only recouped $1 million in box office receipts on the $35 million it cost to make; the fact the $35 million was put up by Muammar Gaddafi also contributed to the film’s doom. As one commentator noted, this was only five years after the demoralizing end of the Vietnam War, and most Americans tended to identify with the fascist Italian imperialists in the film, not with the Libyan insurgent heroes.