The recent Encuentro (or Encounter) At the Border in the middle of Ambos Nogales — the term used to consider Nogales, Arizona, and Nogales, Sonora, as one community — was a wonderful distraction from the Donald and Hillary Show, which may be the most tiresome and preposterous encuentro in American political history.

Pablo Peregrina sings and an acrobat dances at the wall cutting through Ambos Nogales

Pablo Peregrina sings and an acrobat dances at the wall cutting through Ambos Nogales

For two days, from north and south, people trekked to the two Nogaleses to participate in the gatherings and demonstrations critical of the militarized US/Mexico border there. Hundreds of Mexicans and North Americans spoke out for a more humane, more sensible and more constructive border arrangement between the two nations. Citizens of both nations were fed up with the mistrust and paranoia, the growing array of weaponry and police-state surveillance with drones and other mysterious de-humanizing technology — plus the not unusual grisly fact of Mexican corpses encountered in the Arizona desert. The timing for such an encuentro of citizens from both nations was good, given immigration along the border has become a major football in national political scrimmaging.

Donald Trump, of course, is going to build a wall to protect frightened North Americans from the scourge of “rapists” and other brown-skinned demons insinuating themselves from the south by hook or crook into our exceptional, Anglo culture. He’s going to make Mexico pay for this wall, he tells us, by fomenting a trade war with Mexico favorable to the US, thus making Mexico “pay” for his wall. Today, some 580 miles of barriers exist along the entire 1,989 miles of border. There’s currently a very tall and very ugly rusted steel wall running through Ambos Nogales.

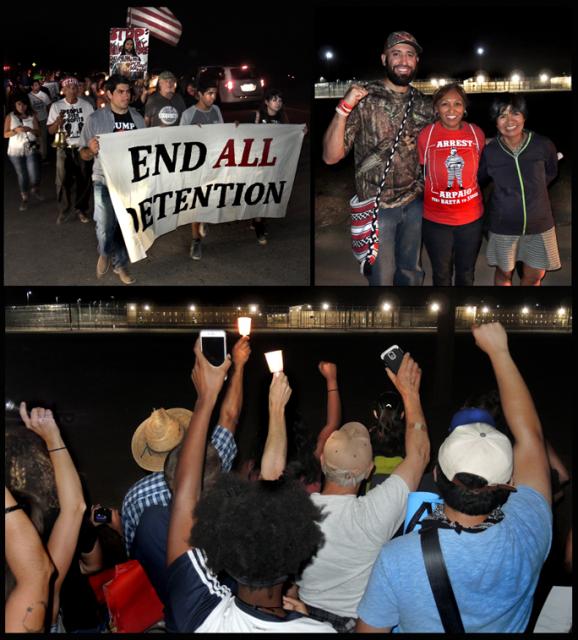

A split rally was held for two days at this steel wall, with people coming from the south and from the north. It was sponsored by the School Of the Americas Watch, a group that had has for 25 years held annual demonstrations at the gate of Fort Benning in Georgia. The Friday before the weekend events at the wall, a large, boisterous rally and vigil was held at an immigration detention center in Eloy, north of Tucson. There were also workshops at a Nogales hotel, where all aspects of the militarization of our southern border were addressed.

Cruising the Historic Borderlands

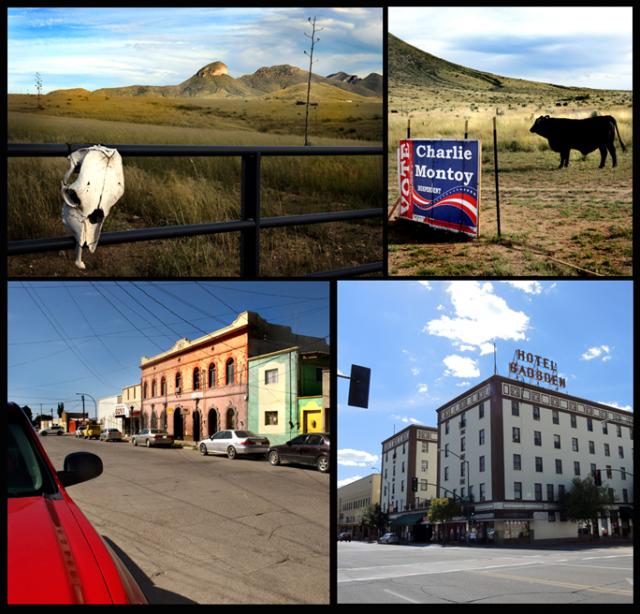

Back in 1968-69, I was home from Vietnam nursing a jaundiced, anti-military attitude stationed at Fort Huachuca, an intelligence base in the Arizona desert 50 miles east of Nogales and 15 miles north of the border. I came early to the encuentro and stayed late, so I could cruise the scrub desert in a rental car in a circle that included Nogales, Tombstone, Fort Huachuca, Douglas and Aqua Prieta. Back in ’68, I had a new Chevrolet Camaro purchased for $2300 through the PX in Vietnam. Not yet 21, I found the outlaw spirit of the place to my liking.

Modern Arizona is a paradox. Tucson development culture is built around golf courses, pumped in irrigation water and air-conditioning; yet the PR imagery of Wyatt Earp and the lawlessness of the Wild West is heavily marketed. There’s the romantic and mythic lure of Mexico evident in classic films like The Wild Bunch and the original Magnificent Seven. On the other end, there’s the current image of Mexico as super violent, thanks to a failed Drug War and the murderous drug gangs that rose to fulfill the supply side in a classic capitalist supply-and-demand formula. Latin American leaders have pleaded with US leaders to address the incredible demand side north of the border. It seems we’re culturally addicted to police, military, courts and prisons as a solution. The Nogales Border Wall is another ugly symbol of all this.

Back in 1968 there was no wall. I became quite comfortable with the border then and felt fine driving into Mexico in my new Camaro. I don’t recall anything about passing through the border; it was downplayed and didn’t amount to much. That was 48 years ago. The border today, in post-911 freaked-out America, is absolutely inhuman.

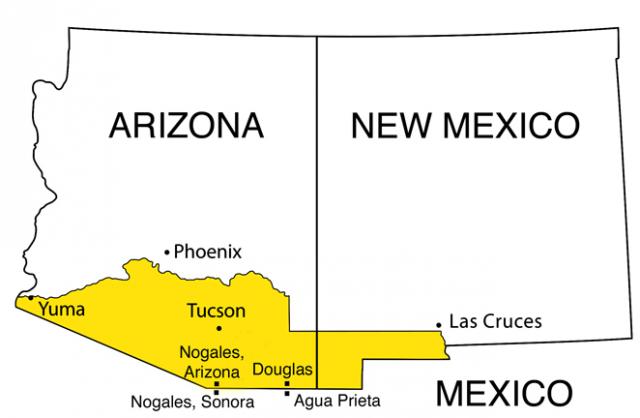

The history of the borderlands is interesting. The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo ended the Mexican-American War. From that, the US grew by 1/3, gaining California, Arizona, Nevada, Utah and the western halves of New Mexico and Colorado. By 1853, the Mexicans were in economic bad straits and grudgingly accepted $15 million for what is called The Gadsden Purchase, additional lands south of Tucson, east to Las Cruces, NM, and west to Yuma, Arizona. It was Manifest Destiny, to open a railroad right-of-way to deliver settlers to California; a route north of the Gadsden lands was too mountainous for a railroad.

The Gadsden Purchase lands

The Gadsden Purchase lands

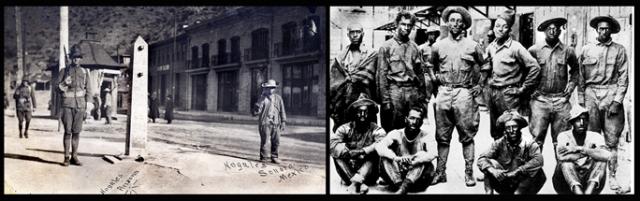

By the early 20th century, the US was at war in Europe against Germany and the Mexicans were going through a tumultuous revolutionary decade. Mistrust grew from both sides. The US feared German fifth column activity in Mexico, and Mexicans were angry at being treated by the US with disrespect. Pancho Villa’s forces were badly beaten in October 1915 by President Carranza’s army in the Battle in Aqua Prieta, the bordertown adjacent to Douglas, Arizona. President Wilson had betrayed Villa (he thought Wilson was on his side) and allowed 3500 of Carranza’s troops, unbeknownst to Villa, to take a US train through US lands from Juarez to Agua Prieta. Villa was furious. For revenge, he attacked Columbus, New Mexico. The US, then, sent troops into Mexico led by General Pershing to get Villa. At the Battle of Carrizal, US Buffalo Soldiers from Fort Huachuca, due to a mistake, ending up fighting the forces of Carranza allied with the US, a debacle that, to Villa’s delight, ended the Pershing expedition.

The Nogales border circa 1915 and black Buffalo Soldiers at the Battle of Carrizal

The Nogales border circa 1915 and black Buffalo Soldiers at the Battle of Carrizal

US troops withdrawing from Mexico in 1917 at the end of the failed Pershing expedition

US troops withdrawing from Mexico in 1917 at the end of the failed Pershing expedition

There were three military skirmishes in Nogales. The major one, called The Battle of Ambos Nogales, was on August 27, 1918. There were unfounded reports of an attack in the works, and US fear was high. The tightening of the border angered Mexicans, who felt they were being treated disrespectfully by US border agents. The precipitating incident was a Mexican with a large package. It’s unknown why or by whom, but a shot was fired in the vicinity. The Mexican with the package dropped to the ground to protect himself. Mexican customs officers thought he had been shot by a US agent, so they opened fire on the Americans, leading to a wild exchange of gunfire that spread south into Nogales, Sonora, soon augmented by US troops from a nearby camp. The fighting ended up in the “red light” district, where the local prostitutes recognized US soldiers they knew. A First Sergeant Thomas Jordan reportedly remarked, “I got a laugh when one them spoke to a trooper, saying ‘Sergeant Jackson! Are we glad to see you!’” Some of these women grabbed bed sheets and bravely ministered to the wounded. The mayor of Nogales, Sonora, waved a white flag trying to stop the carnage and was shot dead from the US side. Soon, cooler heads prevailed and it was over: Five US dead, 16 wounded; it’s uncertain how many Mexican casualties there were, but there were more than US casualties.

A report laid the blame for the outbreak of violence on “frequent cases of insolence and overbearing conduct” by US customs inspectors and “resentment caused by US killings along the border during the previous year.” One US agent was fired. A two-mile-long fence was put up separating the two Nogaleses.

This historic sketch of southern Arizona would not be complete without noting the 1871 Camp Grant Massacre, which set a tone for the rest of the 19th century and even into the modern era. Camp Grant was located northeast of Tucson, by then a key commercial way station on the route to California. Under policy set by President Grant, a Quaker military officer had set up a camp to feed and shelter 500 starving Apaches. At the time, the US Army saw itself as “protecting” Indians from the civic and business leaders of Tombstone and Tucson; at the time, Tucson leaders were called “The Tucson Gang.” These folks were convinced the Army’s camp was breeding hostiles — ie, the “terrorists” of the time. Calling themselves the Tucson Committee of Public Safety, they mounted a raid in which they killed and scalped 150 people, mostly women and children, since most of the men were away from the camp. The military was caught by surprise and did nothing. President Grant was outraged and demanded a murder trial, and it took 19 minutes for a jury to acquit the 100 people charged. The massacre was soon forgotten as development growth increased. A guerrilla war grew and went on until the last 35 starving warriors under the famous Geronimo gave up and were sent by train to imprisonment in Florida. The good people of Tucson and elsewhere grew to accept incidents like Camp Grant as unfortunately necessary to enable the destined Anglo way of life.

The Encuentro At the Border

Landing in Tucson last week as a 69-year-old, wiser version of the unruly youth there in the late 60s, the first thing I noticed driving south on Interstate 19 was all road signs south of Tucson give distances in kilometers. I scanned the radio dialed and found more than half the stations were in Spanish. The borderland is thoroughly bilingual. The encuentro crowd had not arrived yet; in the evening, the motel bar was populated by Mexicans singing karaoke ballads of love and death and beloved horses. It provided me the opportunity to practice my bad Spanish. One Mexican man I spoke with in English — he was a US citizen — told me how he was humiliated as a kid when he spoke Spanish in school. This is normal behavior for a dominant culture — in this case, Anglos; suppress the language of the dominated culture. I explained to this man the politics of the encuentro, and he and his woman companion gave me a thumbs up.

It began to grow on me that it was too late to stop Mexicans and Mexican culture from having a powerful demographic power in the Arizona borderlands. One, Mexicans had lived as citizens in the area in the mid-nineteenth century when it was under Mexican sovereignty; suddenly, they were second class citizens in an Anglo culture. Two, in the age of cell phones, computers and social media, cultures cannot be geographically confined as they once were. And three, the effort to keep southern Arizona “Anglo” feels like a last-ditch effort to keep alive the Manifest Destiny spirit of the original settlers. I submit that spirit focused on keeping hostile Apaches at bay to the east and resentful Mexicans on their side of a hardening border to the south pervades the subsequent commercial agents of development to this day. The question now is, how to sustain the integrity of a national border without doing violence to the humanity of a respectful, mixed cultural community. The answer would seem to lie in a pragmatic approach that accepts the borderlands as a cultural gray zone: Exactly what is suggested by the label Ambos Nogales.

The US/Mexico borderlands and immigration problems are also complicated by events in places like El Salvador and Honduras, which suffered during the Reagan eighties and afterwards. The rise of incredible violence following the 2010 coup in Honduras — accepted by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and the Obama administration — has fueled immigration pressure. This is clear when you consider the fact there are virtually no immigrants coming north from Nicaragua. Add all this up, and it becomes clear why the “dialogue” between the US and Mexico/Central America over the years has not been a healthy one, especially for the poor and powerless south of our border. As mentioned earlier, the Drug War and the ruthless corruption it breeds is, of course, all tangled up in this lack of dialogue and respect.

Miles of desert grassland separate border communities; bottom left, Agua Prieta, right, Douglas

Miles of desert grassland separate border communities; bottom left, Agua Prieta, right, Douglas

It’s not hard to argue that in US culture there’s a significant strain of the “I see nothing!” spirit that accepts outrages like the Camp Grant Massacre as necessary in American history, especially during times of stress. The modern equivalents of the Camp Grant incident tend to be covered up by a severe and rigid regime of secrecy and a patriotic mainstream press habituated to self-censorship. Don’t ask too many questions. Whatever they’re doing, it’s for your safety and security. As George Bush put it, the best thing an American citizen can do for America is don’t ask questions and go shopping.

The militarization of the borderlands now feature full-stop, car-search military checkpoints on US Interstate Highways like I-19 from Nogales to Tucson. You’ve been driving 75 MPH or more and suddenly you’re stopped under a huge awning over the roadway. A man in camouflage carrying an automatic weapon walks up and looks into your car. “How you doin’, sir?” “I’m good.” The armed man radiates a subtle sense of suspicious, as if I’ve done something wrong. He nods, “Have a nice day, sir.” Apparently there are many of these kinds of checkpoints in Arizona and California. An encuentro workshop speaker reported that in the agricultural Central Valley of California such checkpoints are set up on an east-west basis, which he concluded was meant to keep “illegals” in the agricultural zone and prevent them from moving east or west.

The 19th and the 20th centuries are now history. Tucson has been designed and developed into a dense, irrigated miracle of air-conditioned suburban boxes in the desert centered on golf courses and connected by highways. Tom Zoellner writes in his excellent book A Safeway In Arizona: What the Gabrielle Giffords Shooting Tells Us About the Grand Canyon State and Life in America that the Arizona miracle has serious cracks, one being a worrisome dearth of social connectivity despite, or because of, all the developmental growth. Conservative Arizona governments focus on low taxes and minimal services. In some quarters, fear, political reaction and the potential for Second Amendment violence harkening back to the Wild West days may be the most powerful social connection. Here’s Zoellner:

“[Tucson] had rocketed to prosperity on the same factors that had driven the Gadsden Purchase in 1854: race and technology. The race question had been one of American slaves and not cheap Mexican labor, and the technology had been that of the railroad instead of the automobile. But the base factors were the same.”

It’s encouraging that the Clinton campaign has not written Arizona off and is sending Hillary surrogates there for speeches. The notoriously right-wing Sheriff Joe Arpaio of Maricopa County in the Phoenix area is now facing charges of ignoring a federal judge’s ruling and could conceivably go to jail. His run may be ending. There seems to be a significant element of decent, even progressive, people in the borderlands — people who volunteer with many wonderful organizations like No More Deaths that do things like keep full water bottles at key points in the harsh desert for people coming from Mexico. When it comes to border fiction in popular culture, sensational violence often rules; the recent film Frontera (Border)is the smart exception. Ed Harris plays an Arizona borderlands rancher who comes to a very human and workable peace over his border fence with an illegal Mexican character played by Michael Pena who was wrongfully charged with murdering his wife.

The SOA Watch group that sponsored the Encuentro At the Border is expected to repeat the event next year and in years to come. Veterans For Peace was a strong presence there, and is expected to continue an interest in the border. It would be wonderful to see the idea of an encuentro at the US border in Ambos Nogales grow into a movement to bring sanity and humanity to our border. As in the annual demonstrations at Fort Benning in Columbus, Georgia, the local newspaper, The Nogales International, cited how much business the encuentro brought into Nogales. The Americana Hotel was filled to capacity for the first time in its history. Efforts to humanize the border are good for business.

Put it on your calendar: Next Year in Ambos Nogales!

Veterans For Peace march to the wall; carrying a banner for deported US soldiers

Veterans For Peace march to the wall; carrying a banner for deported US soldiers

At the Eloy Detention Center, demonstrators holler solidarity and an Arrest Arpaio t-shirt

At the Eloy Detention Center, demonstrators holler solidarity and an Arrest Arpaio t-shirt