Life is overflowing with metaphorical material. Maneuvering through reality is a constant dialogue and negotiation between what’s inside our heads and what’s going on outside in the chaotic flow of what is. We understand what’s outside by comparing it with what’s inside. This is true whether or not the average anti-intellectual Joe Sixpack or Joe the Plumber recognizes it or not. In fact, those who don’t understand this process are the ones most swayed by metaphor and symbol because they don’t see it working on them.

This dialogue between inside and outside is what it means to be human. It’s also how power is parsed out in all cultures, especially ours. And in America, football is a big player in the process.

For all the above reasons, the just released Freeh Report on the Jerry Sandusky cover-up at Penn State is pretty incredible. In today’s New York Times, stories that started on both the Front Page and the Sports Page jumped to the Business Section. The story touches on a number of sensitive chords. The cable news shows love it.

The Penn State Campus, Jerry Sandusky and Joe Paterno before the fall

The Penn State Campus, Jerry Sandusky and Joe Paterno before the fall

Like nothing we’ve seen lately, it lifts a huge and heavy flat rock to reveal dark, wriggling life underneath. It’s like the opening scene of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet where an old man watering his lawn in an antiseptic suburban community suddenly suffers a stroke. The hose in his hand falls and becomes kinked, the perfect metaphor for a stroke. His head hits the grass. We begin to hear sounds of teeth crunching and struggle as the camera drops with a macro lens into the grass, to reveal a chaotic, Darwinian world of insects and survival of the fittest.

It’s a powerful metaphor to open a neo-noir film about the underbelly of seemingly ordered American suburban life. It leads to one of Dennis Hopper’s most menacing roles as a petty gangster.

The Penn State narrative is one of twisted sexual predation, institutional secrecy and cover-up. There’s the revered status of Penn State in State College, PA — known as “Happy Valley” — and the empire built by Coach Joe Paterno, known affectionately as “Joe Pah.” Paterno was a beloved and powerful man known far and wide for the great things he did for his school and his community. The extent of his fall from grace is not yet fully understood.

Certainly many people will reject where I’m going with this and insist that using the Sandusky incident as a metaphor is — to employ another metaphor — to be a vulture exploiting a vulnerable institution when it’s wounded. And there’s a bit of truth to that, since if the “wound” we’re talking about at Penn State is the fact covered-up truth has been belatedly revealed it’s obviously those who favored a cover-up who are vulnerable targets. To keep the metaphor going, it’s to avoid vultures like me that the cover-up was undertaken in the first place.

Personally, I’m the object of jokes among male friends for finding football boring. I could care less about all of it. I do, however, often like the camaraderie of watching a game with friends over beers accompanied by all the male bonding that goes with the institution. Like everyone, I’m complicated — or, if you like, a hypocrite.

Before I get to the point of this essay, there’s one thing that needs to be said about the Sandusky affair, and it has to do with the nature of male sexuality that underlies the whole pathetic Sandusky/Paterno affair.

It’s about how boys will be boys and how a man can, if permitted, regress to a psychological place where a nostalgic longing for the wonders of innocent boyhood crosses wires with his sexuality and suddenly he’s luring 10-year-old boys into the shower … and, well, we’ve all read of the tawdry testimony. Anyone who has been in the military or in a male-only institution knows the ages-old rule about shower etiquette: “Don’t drop your soap.” As I think Freud would agree, one of the basics of male sexuality is “any port in a storm.”

The point is, in this case, a powerful, grown man went beyond the pale and manifested in the world a predatory monster from within himself, and the institution he worked decades for concluded that his victims were expendable and less important than the institution itself.

The Sandusky Affair as Metaphor

Since President Obama’s Memorial Day speech at the Vietnam Wall in Washington, Vietnam veteran friends and I have become aware of a $5 million-a-year Defense Department effort to clean up the image of the Vietnam War. It’s called the Vietnam War Commemoration Project, and it will be in operation for the next 13 years.

In 1966, I was a 19-year-old kid with a radio direction finder in the mountains west of Pleiku. My job was to locate young Vietnamese kids doing service for their nation just like I was doing service for mine; the difference was I had invaded their nation and they were defending theirs. My goal was to locate them and pass the coordinates on to infantry and artillery units or for Air Force B52 bombers to kill and destroy them. Later after a lot of reading, I concluded the Vietnam War never should have happened. The lesson for me was that there were much better, smarter ways to deal with the issues of the time than war and bombing campaigns. The fact the Vietnamese beat us in the end further makes the whole enterprise a vast and tragic waste of lives and treasure. It was a debacle.

Besides the fact both are fresh in my mind, what do the Jerry Sandusky case and the Vietnam War Commemoration have in common?

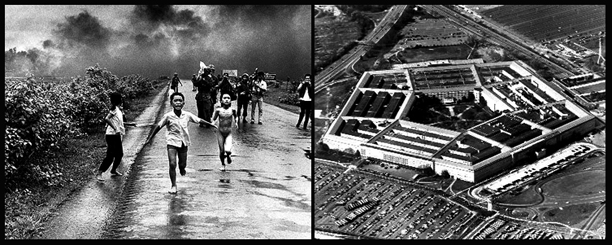

The dynamics of the Sandusky case, for me, reveal like nothing else the way we as a culture aggressively tamp down and hide the unpleasant facts of our past and willfully choose to look only at the honorable, positive aspects of history. The effort to clean up the Vietnam War in the minds of Americans is just such an after-the-fact cover-up.

Here’s former FBI Director Louis Freeh in his report on the Penn State cover-up:

“In order to avoid the consequences of bad publicity, [Penn State leaders] repeatedly concealed critical facts relating to Sandusky’s child abuse from the authorities, the board of directors, the Penn State community and the public at large.”

This is a tidy abstract of how we too often selectively view our history and how, especially, our military works in the post-Vietnam era. It’s a process characterized by two very distinct modes of operation: Secrecy and Public Relations. For the public, the press and leaders outside the power loop, the facts of an operation — even many aspects of the entire war — are kept secret, and public relations is spoon-fed to the public. Between these two modes there is a major struggle for the secret facts, a struggle notable for famous cases like the Pentagon Papers and WikiLeaks. It’s also the playing field for good, solid journalism. At some point, too often, the issues of press access, power accommodation and good ol’boy relationships mitigate against the revelation of information.

.

.

The point is the struggle for the truth. In the case of a deeply dug-in National Security State like the United States, it’s very hard to lift the huge flat rock under which the facts of warfare and history reside in their wriggling and often horrific reality. Instead, we get the pretty narrative dished out to us by Public Affairs lieutenants and colonels.

In campaigns like the Vietnam Commemoration Project, the emphasis is drawn away from real, unpleasant history and questions as to whether or not the causes for the war really made any sense at all. Instead, the focus is put on honor and bravery and individual soldiers and veterans. This, of course, is intentionally designed to put on the defensive anyone emphasizing the war’s unpleasant history. One is suddenly put in the position of attacking the moral heroism of American troops.

At this point in the exercise I always concede that individual honor and bravery are possible in a disastrously wrong war like the one we pursued against the Vietnamese directly or indirectly from 1945 to 1975. But to only focus on American heroism and the suffering of Americans is a disservice to the truth. The fact is, the Vietnam War was a debacle for everyone involved — no matter who won or lost. And it was the Vietnamese who were defending the unified Vietnam that exists today who suffered the most.

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton just toured Laos, where she witnessed kids still being blown up by the lingering munitions we dropped on innocent peasants. It’s hard to clean up a situation like the bombing of Laos — unless you rely on ignorance of the facts. Likewise, there’s the continuing generational legacy of Agent Orange in the ecosystem of Vietnam. And the many instances of My Lai-like atrocities that have never been fully reported. There are many dark, wriggling facts under the heavy rock being kept in place by the Vietnam War Commemoration Project.

It’s easy in retrospect to understand why the powers-that-be at Penn State covered up the facts of an assistant football coach’s criminal behavior. They did it to protect their institution’s image, to keep it clean in the public mind and to assure recruitment would remain robust in the future. This morally dubious equation is laid out unambiguously in the Freeh Report.

There is a world of difference between Jerry Sandusky’s behavior and the truth about the Vietnam War. But in the realm of metaphor, there’s no doubt the same strong urge to protect an institution, to clean up its image and to assure its recruitment capacity for the future is at play in the Pentagon’s Vietnam War Commemoration Project.

Real lessons cannot be learned unless the real truth is known. The American people deserve more than public relations. They deserve to know what has been done — what is being done — in their name. Because, contrary to the famous Jack Nicholson line, Americans can handle the truth.

If the nation is ever going to move beyond repeating the same debacles over and over, Americans better learn to handle the truth.