The conquerors of America glorified the devastation they wrought in visions of righteousness, and their descendants have been reluctant to peer through the aura.

– Francis Jennings, The Invasion of America: Indians, Colonialism, and the Cant of Conquest.

During the summer of 2020, an angry mob tore down a public bust of Ulysses Grant in San Francisco. I wondered at the time whether whoever did this could discern that, while Grant may not be Che Guevara, he did lead Lincoln’s army against the Confederacy, who were the bad guys in 2020’s fraught street demonstrations.

I’m not an expert on Grant, with whom I share common ancestors, Matthew and Priscilla Grant, who came over on a ship in 1630, landing in what is now Dorchester, Boston. From childhood, Grant had a way with horses that helped him as a military man. The famous charge that he was a drunkard or drank heavily has been completely debunked as “utterly and maliciously false” (that from his secretary of state, Hamilton Fish). The rumors were begun out of jealously from soldiers who resented his rapid rise in rank; the rumors then gained traction and followed him his whole career. After Grant’s 1863 victory at Chattanooga, General David Hunter was sent to assess the drinking rumor and concluded this: “He is modest, quiet, never swears, and seldom drinks, as he only took two drinks during the three weeks I was with him.”

[The defaced Grant statue on and off its pedestal in San Francisco. A colorized photo of Grant from the History Channel, and Grant suffering from throat cancer writing his memoir. He died four days after completing it.]

Grant was, ironically, said to be a gentle man who hated the sight of blood, yet he oversaw and managed the killing of many tens of thousands of people to end slavery and bring the Confederacy to its knees. As president, he put up a valiant fight during the Reconstruction Era to do justice by freed slaves and to crush the Ku Klux Klan. He also appointed the first Native American to be the federal Commissioner of Indian Affairs. He avoided public expressions of religion and did not seek to humiliate those he’d conquered. He was, actually, quite a centered, sober sort of fellow who, when he was away from them, profoundly missed his wife and children. (Ronald C. White, American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses Grant, 2016.)

Yes, in the end, Reconstruction failed and Jim Crow grew, leading to lynchings and, if you like, all the realities of institutional racism down to the murder of George Floyd. And, of course, the chronic problems that persist on our “Indian reservations” remain one of America’s marks of shame, hidden out of sight from most comfy white Americans. But it’s off base to blame Grant for all this; he did his best. Frederick Douglas — who Donald Trump bizarrely honored as alive and doing “an amazing job” — eulogized Grant at his August 1885 funeral, saying: “In him the Negro found a protector, the Indian a friend, a vanquished foe a brother, an imperiled nation a savior.” Grant’s funeral march in New York City stretched for seven miles and included 1.5 million people.

Was Grant a slaveholder? Technically, yes. The 1850s were not a simple time. His father Jesse was an abolitionist, but when Ulysses married Julia Dent, much younger than himself, and took over her father’s Ohio farm, slaves lived on the property. Neighbors reported that Ulysses was an especially hard worker and labored hand-in-hand with these slaves, who he treated well. He chose to free a 35-year-old slave named William Jones that he “owned” through a court; this, at a time he needed money, when he could have sold the man for over $1,000. He was powerless to free his father-in-law’s slaves who lived and worked on the farm. (White, American Ulysses.)

Grant was a man who kept his emotions and thinking to himself, though he eventually did take sides against his slave-holding father-in-law. It seems reductive and simplistic to damn Grant for this. As it seems equally unrealistic to expect 2020 rage in the streets to be interested in complexity and nuance.

Being a Grant, maybe I’m a bit sensitive. But only ignorance of history can explain ripping his bust down. But some people may want to encourage confusion; and, of course, we can’t discount the possibility right wing provocateurs might see insulting a statue of Ulysses Grant as a way to incite people like me to write essays like this critical of the rabble on the street. The fact is there are statues that should be brought down from where they’ve overlooked us for decades from public pedestals. City leaders just took down a very prominent statue of the racist polemicist John C. Calhoun in Charleston, South Carolina. Lots of Confederate statues are coming down in the south, many of them erected in the 1920s during a resurgence of racism. Philadelphia finally took down the statue of our bellicose Mayor Frank Rizzo, famous for saying he was going to clear the city of protesters and “make Attila The Hun look like a faggot.”

THE 1637 PEQUOT MASSACRE IN CONNECTICUT

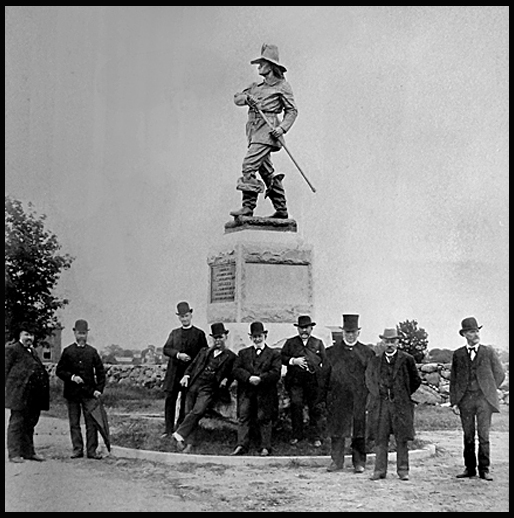

In the early 1990s, there was a statue controversy in Connecticut that related to Grant clan history. The struggle was between the family of John Mason, a military man who led the 1637 Pequot massacre, and the modern Pequot Tribe that had gained local power due to the huge Foxwood gambling casino. This struggle is instructive, since the real issue was not so much the statue itself but the greater view of history the offensive placement of the statue symbolized. To the Pequots, the massacre site has been sacred ground since 1637. The statue of Mason grabbing for his sword was erected in 1889 on the site of the grisly massacre on a hilltop overlooking the Mystic Seaport tourist attraction. Little is said of the nation’s first major Indian massacre across the small body of water and atop a hill. The only memento was the statue of Mason who led the massacre. After a long public squabble, the statue was moved from the massacre site (now a middle class residential intersection) north to a park near the original palisaded fort of Windsor in central Connecticut.

[The John Mason statue on the massacre site in Mystic in 1889.]

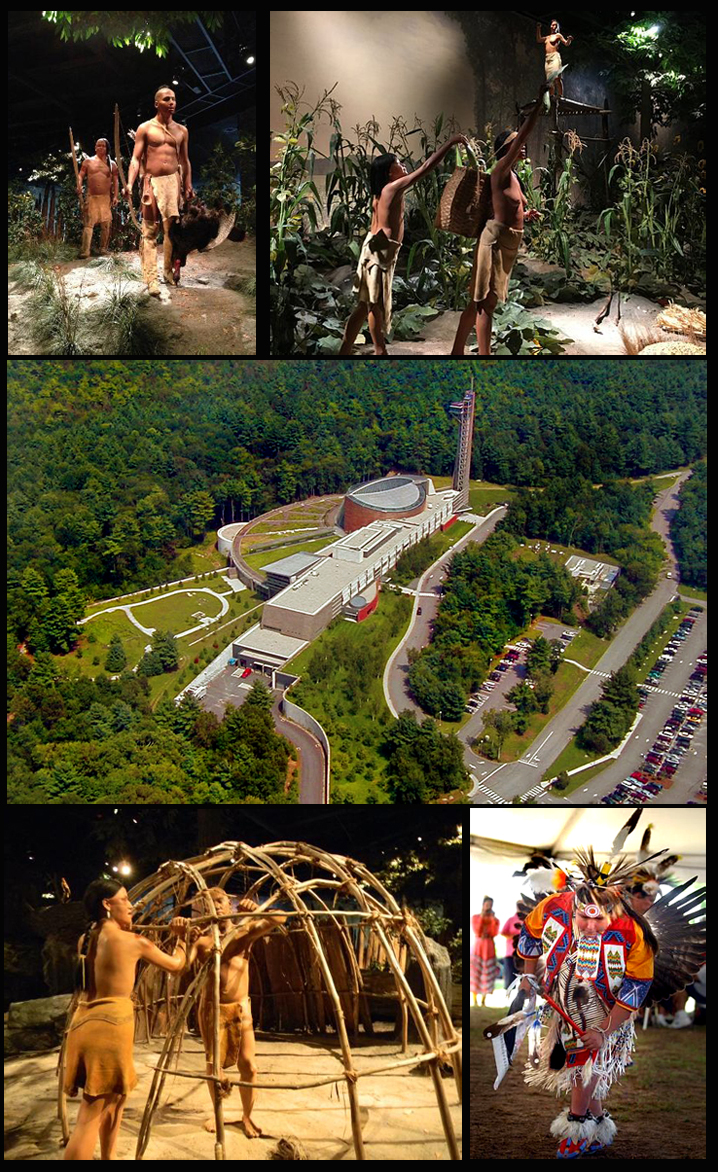

[The Pequot Museum in the woods near its Foxwood casino in central Connecticut. Gambling gave them the power to have the Mason statue moved and to tell their story and the story of the 1637 massacre]

The real issue was, and still is, whether the story of John Mason’s slaughter of the Pequots is something to glorify or something to be regretted or ashamed of. The Mason family member who fought hard to keep it at the massacre site insisted only God could judge his ancestor. Either way, the bloody facts should be taught in our schools, since the 1637 surprise attack on the Pequot fort is important as the first major example of White Europeans massacring Native Americans. The long westward expansion known as Manifest Destiny followed, a movement that went on to include so many massacres it earned the label genocide.

Let’s not kid ourselves: For Native Americans, it was a holocaust.

Matthew and Priscilla sailed from Plymouth, England on a ship named The John & Mary headed for the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Grant mentions them on the first page of his memoir, which was written as he was dying of throat cancer and is considered one of the finest memoirs ever written; it was published by Samuel Clemens. I’ve read accounts of Matthew and Priscilla’s passage, and it was apparently quite miserable; the ship they contracted to make the voyage had been used to carry fish — so it stunk terribly in the hot sun. When his ship reached Massachusetts, the captain of The John & Mary lost his nerve and, afraid of the rocks, let his passengers off on a spit of land. Then he waved, “Godspeed!” and turned his ship back to England. The only good thing one could say about the passage was it was light-years better than the passage forced on Africans delivered to America as slaves.

Matthew and Priscilla and others on the ship, including John Mason, were all scared. Where had they been left? Where was the Massachusetts Colony? Obviously, they didn’t have cell phones and GPS. So what did they do? They did what any intelligent person would do: They made a camp and tried to figure out where the hell they were and how they might sustain themselves until they found the English settlement.

What happened next occurred to other immigrant English people in the early 17th century; the story has been told over and over so much it was turned into a national holiday, Thanksgiving. The English set up their camp and no doubt set out sentries; they did what they could to feed themselves and their kids with what they’d carried with them. Then, one dark night figures began to appear cautiously out of the dark forest. Natives of the area walked in carrying fish and corn and other life-sustaining food. That’s the account I read from Matthew and Priscilla, very vulnerable people at the time and very grateful for the aid and comfort. They might all have been slaughtered — men, women and children! But they weren’t. They were fed and, thus, welcomed with kindness to what was for them a “new world.” With the help of the natives, they soon built a settlement near where they landed in what is now Boston’s Dorchester area.

But life in the Massachusetts Colony was, by this time, very busy and gaining population. So, eventually, my people decided life was too hectic — too many hoops to jump through set up by old hands who had been there for some time. So Matthew and Priscilla, John Mason and the rest lobbied and got permission to move west into Connecticut, where they remained under the rule of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. It was a rugged and dangerous time to say the least. It was one of the first westward moves of a powerful compulsion to keep moving westward, to carve out and make “manifest” one’s “destiny” in the open spaces beyond the reaches of civilization and settled communities with rules to obey and people to pay fealty to. Those with an adventurous spirit wanted raw frontier, land to tame and develop. In this process they established the town of Windsor, Connecticut, a settlement protected by a surrounding palisade of cut-down-trees. Matthew Grant worked as a surveyor and was the town clerk. John Mason lived a few doors away.

The problem was this was territory fought for and controlled by the powerful Pequot Tribe. Other tribes feared the Pequots, who were fierce and not to be trifled with. Incidents began to happen; people were killed on both sides. Tensions grew. Pequot braves would gather outside the English fort challenging the men inside to come out for various tests of manhood — likely the source of the term “Indian wrestling.” Studies have shown that due to the proximity of barnyard animals and things like chicken- and other poxes, the European was much shorter in stature than the Native American, who had only lived in proximity with dogs. So the Pequot men challenging these English immigrants were comparatively larger and quite imposing.

The tensions grew until the English in Windsor decided something had to be done. It was agreed John Mason was the man, since he had been trained in warfare by the Dutch, had fought in combat and had already successfully dispatched a pirate plaguing the settlers in the waters off Connecticut. He established a raiding party and sailed down the Connecticut River, passing the Pequot fort so as not to alarm them. He met with leaders of other tribes and made a pact; some Mohegan men joined in the raid, though they tended to stay behind the English.

The raiding party crept up into an area known as Porter’s Rocks in the hills behind the Pequot fort, a protected and palisaded affair that covered maybe two acres — with two low, very tight entrances covered at night with brush for security. In the 1980s I did personal research in this area and spent hours sitting in Porter’s Rocks imagining what it must have been like as dawn broke. In their defense, the English men who assaulted the fort were pumped up with fear of the Pequots and envisioned the powerful male warriors killing them and their families. So this was a preemptive attack. It was also a method of ruthless slaughter Native Americans were totally unfamiliar with. In his 1991 book The Skulking Way of War: Technology and Tactics Among the New England Indians, Patrick Malone writes: “Feuds between kin groups and intertribal or interband wars of varying scale and intensity were common. Combat was usually on a small scale, however.” Prolonged sieges and open-field skirmishes involving many men were rare. “In all these forms of warfare, relatively few participants were ever killed.”

I’ve read contemporary accounts of the raid and some great histories; the most famous is Francis Jennings’ The Invasion of America: Indians, Colonialism, and the Cant of Conquest. “[T]he whole story of the Pequot ‘war’ is one long atrocity,” Jennings writes. The Massachusetts Bay English were not, in his view, honest about making a treaty with the Pequots. “When closely examined, . . . the Pequot treaty was a covenant finally broken by the Puritans rather than the Indians.” The English would, he writes, retroactively add new demands at the last minute. Sound familiar? Remember the lead-up to preemptive war against Iraq?

To get the full flavor of John Mason’s raid, it’s best to go to the original accounts. This is 17th Century writing, so it can be confusing to a modern reader. For example, Mason sometimes writes in the first person, then he refers to himself in the third person as “the captain.” Despite all this, the horror comes through very clearly:

“We had formerly concluded to destroy them by the Sword and save the Plunder,” Mason writes. Later he write, “The captain told them that We should never kill them after that manner: The captain also said, We must Burn them.” That is, killing them all individually by sword was impractical, so burning them out was required. Jennings disputes accounts that minimize and excuse Mason’s inclinations toward mass slaughter as part of the “cant of conquest” in the title of his book.

Captain Mason takes a torch and sets a wigwam on fire, and the fire quickly spreads.

“[T]he Indians ran as Men most dreadfully Amazed. And indeed such a dreadful Terror did the Almighty let fall upon their Spirits, that they would fly from us and run into the very flames, where many of them perished. . . . Thus did the Lord judge among the Heathen, filling the Place with dead Bodies! . . . In little more than one Hour’s space was their impregnable Fort with themselves utterly Destroyed, to the Number of six or seven hundred.”

According to Jennings and others, the Pequot braves were off on a hunting party and it was mostly old men, women and children who were killed. Once the fire was set, the English retreated and encircled the burning fort. Here we pick up John Underhill’s account:

The Pequots fleeing the fire were “entertained with the point of the sword. Down fell men, women, and children. . . . Great and doleful was the bloody sight to the view of young soldiers that never had been in war, to see so many souls lie gasping on the ground, so thick, in some places, that you could hardly pass along. It may be demanded, Why should you be so furious? (as some have said). Should not Christians have more mercy and compassion? But I would refer you to David’s war. . . . Sometimes the Scripture declareth women and children must perish with their parents. Sometimes the case alters; but we will not dispute it now. We had sufficient light from the word of God for our proceedings.”

In the accounts, it’s suggested that the Mohegans and other Native Americans along for the raid were deeply shaken and, afterwards, guilt-ridden from being part of such an unimaginably grisly affair. Again, Indians had never fought each other in this manner. Thus, the Mohegans and other tribes quickly aligned with the British as the new Alpha Tribe.

Manifest Destiny kept moving West until it got to the Pacific Ocean, where as some historians suggest, it kept moving westward over the ocean at the imperial urgings of men like Theodore Roosevelt — until it reached the Philippines and eventually Vietnam. Arguably, at this juncture in history, the manifest destiny of the United States has come to a wall in the form of a great reckoning with itself. Or, as Jennings put it, with the “cant of [its] conquest.”

GETTING IT RIGHT

So here we are. Statues are coming down all over like trees with rotten roots in a strong gale. Many like the John Mason statue on the sacred site of a preemptive slaughter were truly offensive. The American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan has agreed to remove a statue of Theodore Roosevelt that has since 1939 dominated the entrance of the museum built in the 1870s. Roosevelt is astride a huge stallion; I know it’s a stallion because as a nine-year-old kid looking up I marveled at the horse’s huge bronze testicles the size of basketballs. I recall pointing them out to my dad. On one side of Roosevelt, there’s a very compliant naked slave holding on to the horse; on the other side, there’s an equally pacified Indian chieftain. Eyeballing the statue, you’d think Native Americans and African slaves were delighted with their conditions in America — thanks to the great man Theodore Roosevelt. Of course, TR was a master of PR and a master bullshitter. Featured so prominently at the entrance to a museum of Natural History, the statue is the literal embodiment of white supremacy.

[The Roosevelt statue at the American Museum of Natural History; the racist ideologue John C. Calhoun on his high pedestal in Charleston, S.C., and Frank Rizzo waves goodbye to Center City Philadelphia.]

Teddy Roosevelt’s father was a founder of the museum; yet, TR’s great- and great-great grandsons are fine with the removal and agree the timing is right. What tends to be overlooked in the midst of street rage is that statues like TR on horseback are actually incredible teaching instruments. Perfect examples of Jenning’s idea of “the cant of conquest.” Cant is defined in my dictionary as “hypocritical and sanctimonious talk, typically of a moral, religious, or political nature.” The timing seems right for discussions in popular culture and in our schools about this cant of conquest. To me, the notion of cant is related to a wonderful little book by Harvard philosophy professor Harry Frankfurt called On Bullshit. Here’s how that book opens:

“One of the most salient features of our culture is that there is so much bullshit. Everyone knows this. Each of us contributes his share. But we tend to take the situation for granted.”

Let’s stop taking it for granted! Let’s forego the marketing and branding bullshit and talk about the past candidly among the races, among the genders and among the generations. Let’s finally “peer though the aura” as Jennings puts it in the epigram at the top. If now is not the time to discuss the cant of conquest in our schools with our children who’s future is at stake, name me a better time? It’s like opening a suppurating wound to clean it and heal it, instead of letting it rot until gangrene sets in and life itself is threatened.

Confession: This kind of thing is easy for me to contemplate, since I’ve been personally doing it since I came home as a kid from a tour in Vietnam and started asking myself what the hell just happened? What was I doing there using a direction-finding radio to locate young North Vietnamese radio operators fighting an invading army from 12,000 miles away that I was a part of? It motivated me to read. It punched up my curiosity. Once I got into it, it became a life’s work and there was no turning back. A good, honest scouring of our history would be good for the nation as it faces an amazing, uncertain future.

The left needs Power. Gambling was good for the vanquished Pequots to empower themselves enough to create an incredible museum to the American Indian in the woods near the Foxwood casino. It empowered them to get the Mason statue moved from the sacred massacre site. The power of economic success — a “black Wall Street” — was what motivated the horrific Tulsa massacre of 1921. That story, like the Pequot massacre, is an empowering story. Why because they really happened and have been covered up by an overwhelming tsunami of cant and bullshit. A recent study of the holocaust in Germany in The New Yorker concluded it was Jewish success that most motivated hatred and violence against the Jews.

In the process of spreading the democratic truth, it should become clear that the misguided persons who pulled down that bust of Ulysses Grant in San Francisco are to be pitied; they should not to be beaten, shot on sight with pepper spray or put away in jail. The point is, the truth of our history needs to be successfully incorporated into the mainstream so it can overcome the cant of conquest and encourage feelings of responsible inclusion in society — instead of feelings of being an outsider with the urge to tear things down.