When Franco Lollia embarked for his protest action outside France’s National Assembly building in Paris on June 23, 2020, the respected anti-racism activist knew something dramatic was desperately needed to end decades of denial and delay on addressing the racial bigotry deeply embedded in the nation that prides itself as the champion of equality for all.

Lollia went to the National Assembly building with the intent to spark a dialogue on the need to get-real on racism. His protest, however, ended with him facing charges for vandalism and a possible prison term if convicted. The arrest of Lollia, his supporters across France and around the world stress, exemplify the very racism that triggered Lollia’s protest.

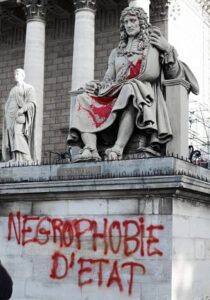

Lollia’s protest targeted the statue outside France’s parliament building honoring 17th Century dignitary Jean-Baptiste Colbert, a revered statesman who initiated the infamous French ‘Black Codes’—the racist set rules that established brutal treatment of slaves in France’s colonies.

Many in France see the Colbert statue in the same vein as protesters in the USA view statutes honoring the Confederates who fought to sustain slavery: monuments that extol white supremacists who caused massive misery for millions of persons of color.

“The French state appoints me as someone who has committed a crime. I just completed by an artistic operation the painting of Colbert for who he was in his entirety: a criminal against humanity,” Lollia stated in an email interview.

“The prosecution in itself is a denial of justice,” Lollia noted. “I am cast into the bad guy role by a country that has proclaimed itself a country of human rights despite all the crimes it has committed. I represent the victims and the state is the culprit.”

The most violent form of state sanctioned racism in France is police brutality against persons of color – primarily Blacks and North Africans.

The day after Lollia’s arrest, Amnesty International issued a report that assailed racially discriminatory police practices in France. Five days before Lollia’s protest/arrest, Human Rights Watch issued a report condemning discriminatory police enforcement in France against children, some as young as 12-years-old. That June 18th HRW report referenced a 2012 HRW report that “documented abusive and discriminatory police stops” in France.

In 2020, fatal violence from discriminatory policing in France began on January 3rd. On that date, a non-white delivery man endured death by suffocation in the shadow of the iconic Eiffel Tower during a traffic stop by four French policemen.

That delivery man pleaded with police seven times that he was “suffocating” during that fatal encounter. That death in Paris was similar to the later May 2020 police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota (USA). Floyd’s suffocation death ignited protests worldwide against the ravages of abusive policing and other forms of institutional racism.

Two weeks before Lollia’s protest, over thirty thousand in Paris staged the largest anti-police brutality march in decades. Protestors condemned the whitewashing of a 2016 suffocation death of a non-white man in police custody. Those marchers castigated an official report released in late May 2020 that proclaimed that suffocation death in 2016 did not result from excessive force by police.

Activists like Lollia declare that May report was yet another example of French authorities excusing the inexcusable. An action by the police chief of Paris amplified the denial of wrongdoing explicit in that official report on that 2016 death. Days after that massive June 2nd anti-brutality protest, the top cop in Paris issued a letter where he proclaimed police were “neither violent, nor racist.”

The Paris police director added insult to his inaccurate declaration when he highlighted the “pain” police feel from false “accusations of violence and racism repeated endlessly by social networks and certain activist groups.”

One French activist group that has criticized abusive and racist law enforcement is BAN, the group where Franco Lollia is the spokesman. The formation of BAN, the Anti-Negrophobia Brigade, came in the wake of the 2005 police brutality-sparked riots that rocked cities across France. BAN has the distinction of being the first organization in France specifically created to oppose abusive policing against Blacks.

Ten days after that June 2nd anti-brutality protest, police themselves staged a demonstration in Paris to oppose the disciplining of officers for racism. Five days before that police protest, authorities announced an investigation into racist and sexist postings in a Facebook group comprised of members of the police force.

French academic Diarapha Diallo, like Lollia, believes earnest dialogue to end the bigoted status quo in France is long overdue. Diallo sees the prosecution of Lollia as persecution of a person working to erase racism in a nation that routinely extends impunity to police that brutalize persons of color.

Diallo, in an email, said reexamination of the propriety of having statues in public spaces that deny and/or praise “past dehumanization” is a critical first step in addressing the racism embedded in French society.

“French people of European descent would be appalled to be forced to live every day in a public space among statues of Hitler and other historical figures that harmed their country. We need a strong inclusive political will to bring forth more diverse people to honor,” Diallo continued. In 1993, Diallo founded the first European support group for imprisoned American journalist Mumia Abu-Jamal. Many in France consider Abu-Jamal a political prisoner due in part to documented misconduct by police and prosecutors that secured his conviction in 1982 for killing a policeman.

An Open Letter to France’s Minister of Justice supporting Lollia’s protest cited the hypocrisy of France’s adoption of a law in 2001 that condemned slavery as a crime against humanity while failing to remedy “the social, economic and cultural injustices, accumulated over several generations, and inherited from the Black Code.” The 40 intellectuals, activists and artists from France and America that signed that letter included American activist/scholar Cornell West. That letter received group support from over a dozen organizations that included BAN, the French Jewish Union for Peace and the Collective Against Islamophobia in France.

Lollia said he splattered red paint on the Colbert statue because he wanted people “to remember the blood shed by millions of Black people because [Colbert wanted] to increase France’s wealth.”

For Lollia, the fact that the statue of Colbert, who said black people were non-human beings, “guards the French National Assembly” means Blacks still lack the respect accorded to whites.

“Western countries like France,” Lollia said, aren’t ready “to hear the reality of our enduring traumas which are a direct consequence of the crimes they’ve committed.”