By Allen Baker

Benjamin Franklin was a prolific inventor and a brilliant thinker. But even he would be amazed at the vast profits that arise simply from printing his portrait on the U.S. hundred-dollar bill.

Here’s how it works: Each year, the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing rolls out roughly a billion crisp new hundreds bearing Franklin’s image. (Think of a goose laying golden eggs.) It then sells those bills to banks. The U.S. pockets, well, $100 billion –- minus 14.2 cents apiece to make the bills.

It’s an economic miracle!

Then comes a second economic miracle. Somewhere close to $80 billion worth of these freshly minted Benjamins (street slang for hundreds) immediately gets spirited across the U.S. border.

That $80 billion number makes paper cash one of the top five U.S. exports, something badly needed in an economy that gets hollowed out more each day. By comparison, exports of commercial aircraft and aircraft engines (think Boeing) hit $99 billion in 2018 — and the profits on those planes are a lot lower than on the Benjamins.

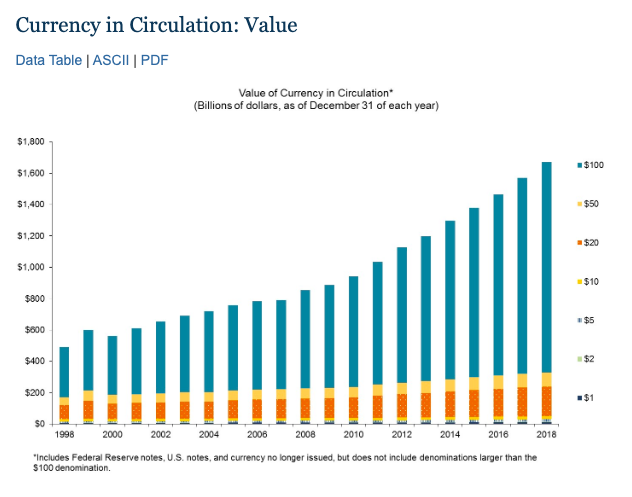

Overall, a total of $1.75 trillion in Federal Reserve notes were in circulation as of Jan. 8, according to the Federal Reserve. Somewhere around, and probably above, $1.4 trillion of that is in hundreds. (There were $1.34 trillion worth of hundred dollar bills at the end of 2018, the most recent number I could find.)

The vast bulk of those hundreds are overseas. Nobody knows for sure just how much, but 80 percent seems like a good guess.

What we do know is this: in nearly every clandestine transaction around the world, and in many legitimate ones, Benjamins are changing hands.

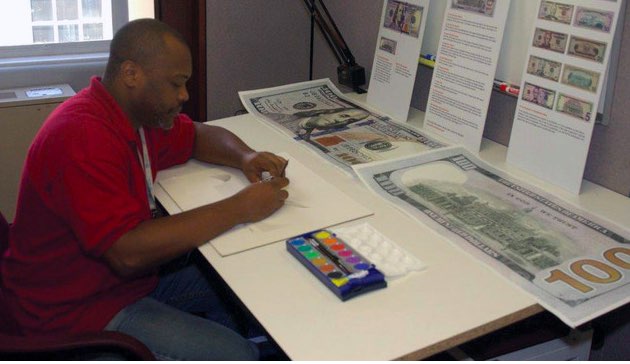

U.S. Benjamins are accepted everywhere. They are small and portable. A million dollars in Benjamins only weighs about ten pounds. The U.S. makes sure those bills have sophisticated anti-counterfeiting measures, thus assuring the drug dealers – and legitimate small businesses still transacting in cash — that they are getting the real thing.

Two economists, Richard D. Porter and Ruth A. Judson, explained the allure very succinctly way back in the October 1996 Federal Reserve Bulletin:

“Today, foreigners hold U.S. currency for the same reasons that people once held gold coins: as a unit of account, a medium of exchange, and a store of value when the purchasing power of the domestic currency is uncertain or when other assets lack sufficient anonymity, portability, divisibility, liquidity, or security,” they wrote. Note the anonymity part. “A safe asset in an unpredictable world, dollars often flow into a country during periods of economic and political upheaval and sometimes remain there well after the crisis has subsided.”

So you can understand how sending threats, helicopter gunships and troops around the world actually serves as a great marketing tool for Benjamins. Every time the U.S. destroys some poor nation’s economy, more Benjamins are needed. (Remember how the US flew C-17 transports filled with pallets of paper money, $40 billion worth of mostly $100 bills, along with some $50s and $20s — into war-torn Iraq during the US occupation, allegedly to help get that ruined nation’s economy moving again? Almost none of that money was ever accounted for.)

Some countries, Panama for example, have been invaded so many times they finally abandoned their own currency altogether and just use dollars. Now that’s marketing.

To give a sense of the scale here, the total amount of currency in the entire world is about $5 trillion, for seven billion people. U.S. dollars represent a third of that. And Benjamins alone account for around 28 percent of all cash in circulation in the world.

As economists Porter and Judson also noted, the currency float benefits the U.S. government in another way. “All U.S. currency, including that held externally, can be thought of as a form of interest-free Treasury borrowing and therefore as a saving to the taxpayer.” As Franklin used to say, a penny saved is a penny earned. Maybe enough pennies to buy a fleet of F-35s.

You may have wrinkled your nose a bit at the notion that exporting cash brings money into the United States. Sounds counterintuitive. In the long run, but only in the long run, it is.

After all, unlike smart watches or those gold coins the economists mentioned above, Benjamins have no intrinsic value. They are just pieces of paper, backed only by the “full faith and credit’’ of the United States. Plus those gunships, of course. And sanctions, lots of sanctions.

You might suggest that one of these days, citizens and leaders around the world will finally get fed up with sanctions, fed up with Uncle Sam throwing his weight around. What happens, you may ask, when they rise up and call a colorful piece of paper just a colorful piece of paper?

Indeed, most likely even before it happens at the official level, drug dealers and swindlers will decide they want something solid like gold bars, instead of those Benjamins. All that cash is now worthless in bazaars around the world.

But wait, it’s still Legal Tender in the United States. So, you guessed it, all that currency will then high-tail it back to the U.S.

There is so much cash in this hoard that the local agents of those drug dealers could pay off most of this nation’s student loan debt. But even though that’s how the Mafia used to keep the neighbors quiet in Little Italy, they probably won’t do it. Figure they will target items that are small, portable and have some intrinsic value. Coins, gems, jewelry, guns, maybe used cars. Maybe they’ll want some real estate too.

In any case, the tsunami of Benjamins, when it hits our shores, will be a mighty economic storm. The most likely consequence would be a huge wave of inflation. Nobody will want Benjamins, not even in here in Franklin’s home nation.

You might ask: So if people don’t want those Benjamins, why would they continue to buy Treasurys to refinance that $23 trillion in U.S government debt?

The answer is, they won’t.

So then what will happen to the U.S. domestic economy, and maybe even the world economy, when people around the world won’t take U.S. dollars or U.S. Treasury “securities’’ any longer?

You’ll need to find someone smarter than me to explain all the ramifications of that one. I can tell you that millions of people, at a minimum, will have their personal finances devastated.

ALLEN BAKER is a long-time journalist who has specialized in investigative pieces and economic analysis. He worked for the Associated Press in Alaska, for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and for several community newspapers and other publications. He contributed this article to ThisCantBeHappening.net