In the Lenin Barracks in Barcelona, the day before I joined the militia, I saw an Italian militiaman standing in front of the officers’ table. … Something in his face deeply moved me. It was the face of a man who would commit murder and throw away his life for a friend — the kind of face you would expect in an Anarchist, though as likely as not he was a Communist. … I hardly know why, but I have seldom seen anyone — any man, I mean — to whom I have taken such an immediate liking.

– The opening of Homage To Catalonia by George Orwell

John McCain is certainly an interesting American politician. To be politically correct, maybe I should call him an American “warrior/politician,” since he’s a key leader in the post-911 culture saturated with the warrior-ethos. Last month, this warrior/politician wrote an op-ed in The New York Times that I can’t get out of my mind.

In the piece titled “The Good Soldier,” McCain saluted Delmer Berg whose obituary had run March 2nd in the Times. (Belatedly appreciating the irony, the Times changed the op-ed’s title online to: “John McCain: Salute To a Communist.”) Berg, who died at age 100, was presumably the last living American veteran of the famous Abraham Lincoln Brigade that fought on the Republican side in Spain against a 1936 fascist coup led by the caudillo general Francisco Franco, certainly a warrior/politician of his day. The Republic had been constitutionally set up and its leaders duly-elected after the monarchy collapsed in 1931. The Soviet Union supported the Republican side and Hitler and Mussolini supported the Fascists. The Republican side had a romantic, underdog quality that drew writers and adventures like George Orwell and Ernest Hemingway.

Proud American communist Delmer Berg in 2014 and in 1938 in Spain, second from right in beret

Proud American communist Delmer Berg in 2014 and in 1938 in Spain, second from right in beret

In 1937, Berg was a 21-year-old dishwasher who saw a poster for the Lincoln Brigade and signed up. He soon shipping out to Spain on an ocean liner; he was eventually wounded and sent home. Of the 3000 American volunteers who fought in Spain, around 800 were killed. The Fascists prevailed in 1939. Berg joined the Communist Party in 1943. The Times called him “an unreconstructed communist.” A newspaper in California asked Berg what were the proudest moments of his life; one he said was “when one of my grandsons was valedictorian at his Oregon high school graduation and said in a newspaper interview, ‘My grandfather is my inspiration. He’s a Communist!’ ”

Like John McCain, I’m a Vietnam veteran. In June 1965, I was an ignorant 18-year-old Army volunteer just arrived at Fort Jackson, South Carolina. I vividly recall being cursed at to get my worthless ass off the bus and badgered to run up a hill to a barbershop, where my hair was sheared off as if I was a sheep. I also recall being presented with a long list of organizations that I was to indicate whether I had ever been a member. I saw something called the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and wondered why something named after such a great American could be considered subversive. My military career went downhill from there.

Unlike John McCain, I didn’t suffer much in my job as a radio direction finder in the mountains and valleys west of Pleiku along the Cambodian border. My job was to locate Vietnamese communist radio operators — ie. a Vietnamese man with a leg key batting out Morse code in five letter groups, along with a second man pumping a bicycle generator. These operators would walk to a different location every day some distance from their unit so invaders like me could not locate their dug-in headquarters. Over time, we’d figure out a pattern, at which point the intelligence brass would send jet jockeys like John McCain to bomb the area in the hope of obliterating all those diminutive communists trying to liberate their country. Then they’d send a long range recon patrol to see if they’d hit anything. For one operation, I got an Army Commendation Medal. We’d located a brigade headquarters.

At age 68, I see the Vietnam War as a cruel national disgrace. Because I’m a humanist (versus a militarist) I don’t preclude within that shameful context individual instances of humanity, bravery and great suffering of the sort that McCain went through as a prisoner of war. Besides being an invader, McCain had the added difficulty of being the son of the four-star admiral who was his ultimate Navy boss in the theater, and the grandson of another four-star admiral in World War Two. It seems fair to say, while I was a dumb kid way over his head, John McCain was 11 years older and highly invested in the enterprise of killing communists.

It’s good to consider the semantics of the word communist. The trouble with referring to communists is that the word is, maybe, the most belligerent and misleading epithet in history. Sure, there’s Marx and then Stalin and all the tyrannical horror associated with his name. But many people throughout history have, like Marx, written about social reform and economics from the bottom up. In the real world, there’s many cases like the Spanish Republic, the Arbenz government in Guatemala overthrown by US coup in 1954, the 1953 coup in Iran, the overthrow of Allende in Chile in 1973 and a host of other duly-elected, left-leaning reformist governments violently destroyed in some cases directly by Americans or dispatched with our blessing. The 2009 coup in Honduras fits this criteria. In all these cases, the word communist was employed as a justification for rightwing violence. During the Reagan years in places like El Salvador, reformers were forced to take up arms to overcome the long-suffered, brutal oppression of the poor and the powerless by what was called “the fourteen families.” The pathetic fact is much of this political history had little to do with the two-dimensional idea of communism — unless, of course, you’re a rightwing blockhead with a gun such as the infamous fascist officer in Spain who presumably said: “Whenever I hear the word culture, I reach for my revolver.” Today, as a female Republican candidate for US Senate in Nevada put it in 2012, it’s known as “the second amendment option.”

So I’m perplexed why John McCain wrote his op-ed honoring Berg. I don’t question his sincerity; I just wonder what the man was thinking. Doesn’t it open a rather messy can of worms? But, then, maybe that’s the point. Maybe it’s John McCain’s way of redefining his legacy, even in some strange way a tactic to deal with his own no doubt quite complex post traumatic stress from aerial bombing over the urban center of Hanoi. He may also see it as a paean to the warrior ethos, honoring a man who fought “for a people who were strangers to him” but who “did not quit on them.” In that sense, if I had any honor at all I would have picked up a gun and fought with the peasants in El Salvador, like the M16-wielding female doctor from Belgium I met in 1986 humping the hills with FMLN guerrillas in Chalatenango. War weariness on both sides led to the FMLN (the Faribundo Marti National Liberation Front) becoming a legal political party that has elected two presidents, including the current one, Salvador Sanchez Ceren, an FMLN guerrilla leader during the war. As McCain said of the Abraham Lincoln Brigadistas, the FMLN “did not quit.”

The access point for McCain in honoring an American communist who fought with the Lincoln Brigade is, not surprising, the late great macho icon Ernest Hemingway and his famous novel of the war in Spain, For Whom The Bell Tolls. McCain read the book when he was 12. I think I was about 15 when I read it. It never stuck with me like it did with McCain. It was the novels of John Steinbeck that moved me as a kid. The rebellious son of a comfortable, white, professional family in the farming area below Miami, in the summers I worked with migrant laborers picking limes for 25 cents a field crate. It wasn’t the honor of romantic armed conflict that moved me; it was the warmth and joking friendship of poor, working people, again borrowing McCain’s words, “people who were strangers to [me].” As a kid I also read Graham Greene’s The Quiet American and (no doubt Graham Greene is rolling in his grave) found the colonial exoticism of Vietnam in the fifties alluring.

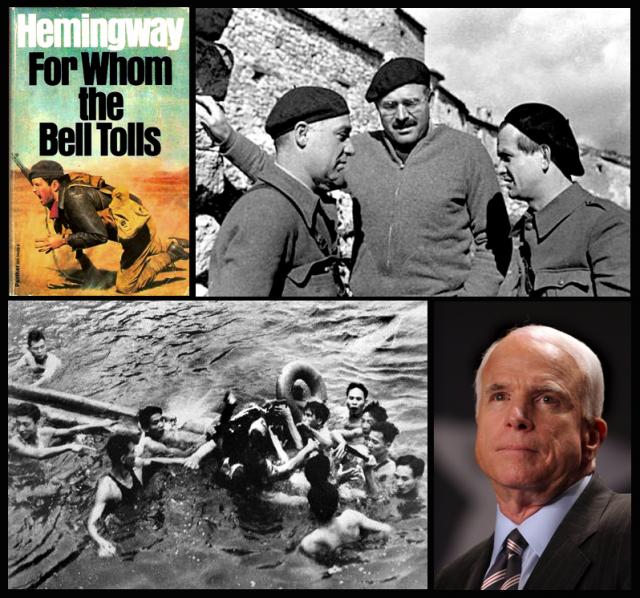

Ernest Hemingway, at top, center, in Spain and John McCain being hauled from a Hanoi lake in 1967

Ernest Hemingway, at top, center, in Spain and John McCain being hauled from a Hanoi lake in 1967

As he wraps up his homage to Berg, McCain uses Hemingway like an ejection seat from a burning A-4E Skyhawk. Hemingway’s hero, Robert Jordan, “had begun to see the cause as futile. He was cynical about its leadership, and distrustful of the Soviet cadres who tried to suborn it.” Orwell famously became critical of this as well. But what’s important to McCain is that Jordan stuck with it. He quotes Jordan, who is killed in the end: “The world is a fine place and worth the fighting for.” The implication is that, while Delmer Berg may have been a card-carrying communist who protested the Vietnam War and fought for civil and human rights, because he took up arms and fought in Spain like Hemingway’s romanticized protagonist, he was a good man worthy of Senator McCain’s respect.

I’ll give McCain the benefit of the doubt and accept his honoring of Berg as from the heart. But I’d be less than honest myself if I didn’t recognize the doubt that simmers in my mind. In the year of Donald Trump as the trash-talking logical conclusion to nearly a decade of Republican obstructionism and white working class frustration, could it be possible Senator McCain has taken this opportunity to show how magnanimous he can be dealing “across the aisle” with the left. With Trump’s loathsome “birther” behavior in mind, many will recall McCain’s admirable handling on the stump in 2008 of a lunatic woman suggesting Barack Obama was a Muslim and a subversive threat. It underlines the fact that, in comparison to many of McCain’s odious Republican comrades, it’s not hard to look like a stand-up guy.

By November 2016, McCain will be 80-years-old. Anywhere but in ayatollah Iran, that seems over-the-hill as far as vigorous national leadership goes. But, then, in a highly volatile, brokered convention desperately looking for a straight shooter with the gravitas to beat the Democrats — who knows? Maybe John McCain would like to fashion himself a spiritual elder statesman above the fray ideally suited to guide a declining imperial America. Maybe presenting himself as a militarist who has suffered but is able to see honor in a tough, idealistic leftist is part of that.

Whatever lurks in the recesses of John McCain’s mind, the instinct to write the op-ed on Berg suggests he’s a complicated old SOB who somewhere holds onto a strain of human decency and love for the underdog. The danger is, like those Soviet cadres he says tried to “suborn” the Republican cause in Spain, there’s also a very robust instinct in the American military character of suborning honorable causes by focusing so hard on “US interests” that ordinary humanity gets lost in the fog and the bombing runs.