On Saturday October 29, 2011 over 500 people from across England protested near the Parliament building in London. What was startling for me, an American journalist covering that protest against brutality by British police, was not who attended but who was absent.

That 2011 protest occurred a dozen weeks after a fatal police shooting of a Black man in North London triggered destructive rioting that swept across London and into many cities throughout England.

Despite those 2011 riots being the worst civil unrest in a generation and despite abusive policing being an issue that roiled non-white communities for decades, British mainstream news media did not deem that October 29th protest ‘news’ worthy of coverage.

That failure by major media to cover that anti-brutality protest denied the public of valuable context about the issue underlying a series of riots in London dating from the late 20th Century. Those disturbances included a deadly October 1985 outburst against abusive policing in the same London community (Tottenham) where those 2011 riots ignited.

Participants in the protest included family members of the victims of brutality that triggered two of those disturbances in the 1980’s and that 2011 outburst. Coverage of viewpoints from those family members, who spoke during the demonstration, could have expanded public understandings about impacts of abusive policing.

Perversely, that 2011 coverage omission also denied the media of a favored focus: conflict. During that 2011 protest, police physically assaulted participants for the first time in the 13-year history of that annual demonstration.

Currently an uproar rattles British news media in the wake of accusations of racist coverage practices that Prince Harry and his wife Meghan leveled during their recent interview with Oprah Winfrey. Those accusations about coverage compound long-standing concerns about the paucity of non-whites working in British news media from reporters to managers.

Reacting to those accusations, the Executive Director of England’s Society of Editors issued a strident denial of racism in British media: “…the press is most certainly not racist.”

That Director’s display of woeful ignorance or willful deception forced his resignation after quick condemnation from journalists and the public. However, others in British media and beyond viewed reactions to that Director’s opinion as another example of left-wing ‘cancel culture’ violitive of free speech.

That Director’s denial statement chided the Duke and Duchess for their failure of making “such claims without providing any supporting evidence.”

Well, if the documentable experiences of those Royals-in-Exile is not enough, a source for documentation about racist media practices by targets of such coverage is London’s Black Cultural Archives. This facility in London’s Brixton section is located about 65-miles south of the Society of Editors office in Cambridge. When I researched community reactions regarding police brutality in the BCA two years ago, one constant community criticism in the files was racism in England’s news media.

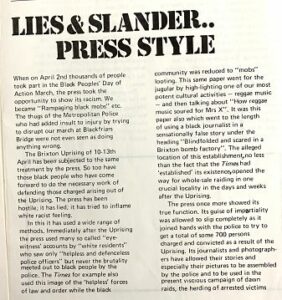

For example, an examination of news media coverage before, during and after the April 1981 police-brutality-sparked riot in Brixton led the then Brixton Defense Campaign to state in its newsletter, “The press seems totally unable to rise above its own racism.”

Information released in July 2020 by the Reuters Institute For The Study of Journalism counters curt dismissals of community perspectives about discriminatory coverage and dismissals of analyses by academics that faulted 2011 riot coverage.

The Institute’s Fact Sheet found zero non-white top news editors in the UK. Non-whites comprise 14 percent of the UK’s population but just six percent of news media employees, with Blacks being 0.2 percent of journalists.

The ruckus over discriminatory practices in UK media does not merit smugness on the other side of ‘The Pond’ where race related news media issues still persist.

Yes, last year media entities like the Los Angeles Times and Kansas City Star apologized publicly for past racist coverage. And, yes, diversity employment in America’s news media is better than in the UK. However, structural problems with coverage and employment remain in America’s newsmedia.

Last summer for example, when civil rights leader Rev. Jesse Jackson, toured Kenosha shortly after anti-police-brutality rioting tore through that Wisconsin city, he released illuminating employment and economic data. That data detailed institutional inequities that drove disparities in Kenosha like unemployment and poverty rates for Blacks being more than double the rates for whites. Yet broadcast and print coverage of Jackson’s tour omitted this data that provided important context about conditions in Kenosha.

There is a simple route to improved coverage of non-whites in both America and Britain. That route is compliance by journalists with non-discrimination standards contained in the conduct codes of America’s Society of Professional Journalists and Britain’s National Union of Journalists.

Discrimination – rather inadvertent or intentional – destroys the accurate and fair coverage that supposedly anchors journalism on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

The final item in the SPJ’s code urges journalist to abide by the “same high standards they expect of others.”