Click here to go to My Vietnam War, 50 Years Later, PART ONE: “A REMF Way Out In The Front”

MEMORY, WRITING and POLITICS

Inside a writer’s imaginative mind things rise from the unconscious and find their way to the fingertips and to the keyboard, where they become words; that place is neither fact nor fiction. That is a fact. Donald Trump has made this fact more clear than maybe anyone ever has in my modern memory. Bao Ninh’s character Kien from the novel The Sorrow Of War and Kien’s ill-fated 27th NVA Battalion are stand-ins, in my mind, for the brigade headquarters I and my direction-finder comrades helped locate for death and destruction. The lush terrain of Vietnam’s Central Highlands is now in my mind as an opening master shot in a movie. The camera is looking out the open door of a Huey in the early dawn hours. There is no door on the chopper, and cool air is rushing into the passenger compartment where I sit on a canvas seat with no seatbelt, holding my M14 rifle. (In 1966, REMFs still had long, wood-stocked M14s.) Everything is green and lush, and the low dawn sun is shining on everything. The winding Se San River looks like a glowing, golden snake slithering through the forest toward the horizon. This incredibly beautiful image is seared into my mind.

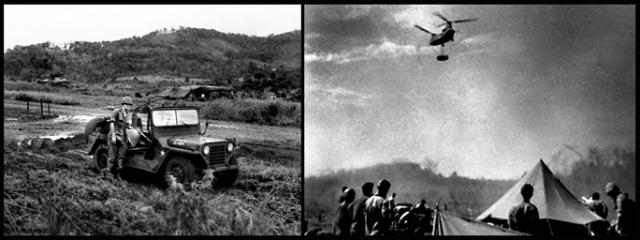

DF team member and jeep at a firebase in the Central Highlands, and a Chinook lifting a load on a sling, the way we moved from firebase to firebase the 3/4 ton truck that served as our map-plotting office.

DF team member and jeep at a firebase in the Central Highlands, and a Chinook lifting a load on a sling, the way we moved from firebase to firebase the 3/4 ton truck that served as our map-plotting office.

Earlier that morning, I’d leaped up onto the top of our three-quarter-ton truck’s box, and as a huge, olive-drab Chinook lowered itself slowly down toward me, I slapped a metal ring onto a hook attached to behemoth’s belly — and jumped crear. I flew next to the Chinook in the Huey and watched the truck with its box containing maps and DF paraphernalia trailing in the wind on the sling beneath the Chinook; a jeep and trailer was being carried inside the belly of the Chinook. Our mobile DF operation was headed toward the border as part of a huge operation to engage and clear the NVA streaming down from the north via the Ho Chi Minh trail and east into the Highlands. There is an amazing sense of power one gets — especially as a kid — from being a part of such a powerful and immense army. I realize now, on missions like this I was looking for young Vietnamese men like Kien and his 27th NVA Battalion so powerfully represented in Bao Ninh’s The Sorrow Of War.

I actually saw men like Kien on two occasions. The first time was a very gaunt, hungry young man in black with a khaki pith helmet, sick with malaria, turning himself in on our firebase perimeter. There’d been a wild shootout along the perimeter the night before; apparently the NVA was testing the camp’s defenses, which were formidable. He stood there with his hands up until armed men walked toward him; they talked briefly, and I’m not kidding, one of the men offered the emaciated kid a cigarette. The second time, I was about to go outside a firebase perimeter to move my bowels, since the shitter was just outside the perimeter for reasons of odor. A rather bemused grunt on guard told me to hold up. “Maybe you don’t want to go out there night now, pal,” he said. He had me look into a pair of night glasses set up on a tripod. Just beyond the shitter, I saw little white ghosts moving back and forth. We’d only been there a few days, and it was news to me that we were virtually surrounded. My bowels tightened up quickly, and I returned to our freshly made two-man bunker, where I made sure my M14 was in good order and my magazines loaded and ready. I soon learned the lieutenant colonel who commanded the battalion had ordered leaflets dropped into the jungle challenging the NVA to hit our firebase. He was virtually calling the NVA “pussies” if they didn’t attack his fine base. The colonel had also ordered mines to be placed around the perimeter. Once the NVA moved on, he ordered the mines to be removed. A detail of privates was assembled for the task, one of whom blew himself to kingdom come. I heard the BOOM! Then lots of hollering and running medics. In the end, a chaplain led a detail of other privates picking up the loose pieces of this unfortunate young draftee.

I later learned that lieutenant colonels like the man who led this battalion served six-month combat tours and often asked their men to do brave things to accrue glory to the colonel’s record so he could make rank in the competitive environment of Vietnam. It was called “punching your ticket.” It makes me think of Jonathon Winters and his routine as Colonel Robert Winglow: “OK, men, you can feel secure knowing I’ll be up on that hill, behind you all the way watching through the long lenses. So, go get ’em, men!”

I’d be remiss not to tell how this lieutenant colonel left our firebase on a stretcher. He passed by me carried by two men, headed toward the LZ and a Huey back to the division hospital. A tough warhorse to the bitter end, he was hollering, “Get that son-of-a-bitch! I want that bastard!” In his wounded condition, the colonel did not realize it wasn’t an NVA sniper who had nailed him. It was a young private cleaning his M16 very near me; he had not realized there was a round in the chamber, and he had sent a round into the colonel’s tent. Incredibly, the bullet went through the colonel’s gut, then veered off through the executive officer’s calf. The poor man had taken out two field-grade officers with one round. A new lieutenant colonel was flown out to the firebase to punch his ticket and spur the unit on to even greater glory. I don’t know what happened to the poor grunt.

While I have no trauma from my Vietnam experience, I have a bad attitude about the military and the war itself. I also have a whopping case of survival guilt. One, because I made it home without a scratch; and, two, because I had it so easy. My thinking now is all wrapped up in atoning for what I’d call my moral cluelessness. Americans who supported the war, I feel, were guilty of some degree of moral obtuseness. As a people, we failed completely to recognize the tremendous suffering we caused the Vietnamese; then, we obsessed on our own suffering, which was hardly comparable. Sure, we lost 58,000 dead, names on a wall in Washington, names that should be honored and mourned. The problem is the Vietnamese lost so many more and suffered so much more than we did. When distilled down to its essence, the war really makes little sense except as an expression of Cold War hysteria. There’s lots of talk about “lessons” learned, but the discussion never really gets at what should have been learned. Few dwell on the fact we slaughtered somewhere between two and three million Vietnamese and Indochinese people. And that’s not counting the immense destruction of infrastructure and upheavals in family life and the legacy of Agent Orange in the ecosystem and a host of other areas of suffering. For what? As a balance to the threat from China, Vietnam is now a friend; we fuel our warships at Camrahn Bay. Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh were our ally in WWII. The Vietnamese never did anything to us here in the US. All they wanted was the removal of the European colonial yoke. And, of course, they won the war.

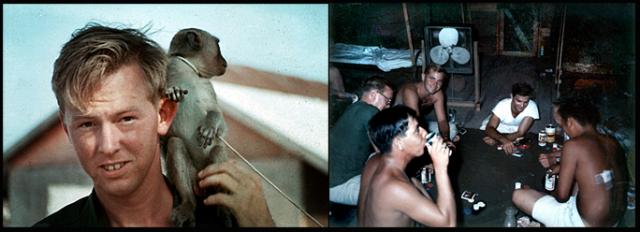

The author on REMF duty in Camrahn Bay: grilling, drinking & whoring.

The author on REMF duty in Camrahn Bay: grilling, drinking & whoring.

In the late 1980s, a very diplomatic, English-speaking veteran from the NVA make a tour of the US; our Veterans For Peace chapter in Philly hosted him. I was on local TV news walking him in the rain under an umbrella past the Philadelphia Vietnam War memorial. He was a good man and very moving when he talked. ROTC officers at the university I worked at saw me on TV with him and made it clear they found it disgusting that I had taken this US enemy to a memorial for US dead. My response was, well, that’s too bad. Later, I saw video of this man in a gathering of US Vietnam veterans in New York where he broke down into sobbing over what seemed to me frustration with the lack of understanding or sensitivity among these American vets to the great suffering of the Vietnamese. In my reading of the scene, these men couldn’t see past the idea of “communist” and could only focus on their own official pain; this seemed to be the case with the ROTC officers, all young men with no war experience — only loyalty to the Army. The pain of these New York vets was, no doubt, very real; but it had to be dwarfed by the pain this friendly, forgiving man represented; he had showed great fortitude and courage to travel halfway around the world — alone — to reveal himself in the midst of American culture. I felt proud walking him past the veterans’ memorial in Philly.

Memories like this only reinforce my disgust for the Vietnam War and the unnecessary evil it represents in my life and in American history. Again, I challenge anyone to tell me what the Vietnamese ever did to us. The historian Mark Moyar recently suggested in an essay in The New York Times series Vietnam 1967 that the Vietnam War was “winnable” — if only we had done this or that differently. To me, that kind of what-if, alternative history is an utter waste of time; it amounts to alternative history fiction like Phillip K. Dick’s novel The Man In The High Castle, an alternative history that imagines the Nazis winning World War Two. Rambo was that kind of alternative history as pop cinema entertainment. Brilliant Hollywood producers figured out they’d grease up Sylvester Stallone — a man who spent the Vietnam War teaching in a girls school in Switzerland — and let him “win” in Vietnam with his trademark sneer, a huge Bowie knife and a hand-held M60. John Rambo did what the United States Army, the Marine Corps, the Navy and Air Force could not do. He emotionally won the Vietnam War inside our hermetically-sealed movie-minds. It’s the same brand of bullshit Donald Trump is spewing to counter the haunting reality of decline that gnaws at our sense of exceptionalism.

The author as 19-year-old REMF at a Camrahn Bay strategic DF site; the crew playing cards and drinking cold beer.

The author as 19-year-old REMF at a Camrahn Bay strategic DF site; the crew playing cards and drinking cold beer.

The Vietnamese beat us fair and square. They didn’t beat us with hi-tech slaughter; there’s no question we would have “won” if life was only about the ability to kill people by the thousands or millions. They beat us on moral grounds. They were right; we were wrong. As Ho Chi Minh reportedly said: “We can lose longer than you can win.” In the ’90s, a Vietnamese diplomat reportedly told Robert McNamara, “We knew you would eventually leave. You Americans could leave. We lived here, and we could not leave.” Or as Ward Just put it in a great little book written in 1968 called To What End: “Of course the war was unwinnable. It was useless to fight the Vietnamese. They would have fought for a thousand years.” There’s so much we could learn from the Vietnamese in the area of humility, resilience and forgiveness. But we prefer to see those traits as the characteristics of a loser and a patsy. We insist on being winners even if, to borrow the famous Eastwood line, it requires us to be “legends in our own minds.”

Truth and Fact are at the core of all this. It’s interesting that the Vietnam war correspondent Ward Just wrote his eloquent 1968 memoir To What End and, then, shifted his career to fiction and novel writing. Dealing purely in reality was not enough. Just was ahead of his time in this respect, anticipating the fact-free, truth-phobic Age of Trump where the art of bullshit prevails. Just quotes the playwright Harold Pinter as an epigram in To What End: “There is no hard distinction between what is real and what is unreal, nor between what is true and what is false. The thing is not necessarily either true or false. It can be both true and false.” A writer’s mind is unlike a lawyer’s mind, which is always dependent on a citation of legal precedent. A writer’s mind is free and, accordingly, dangerous. The philosopher/longshoreman Eric Hoffer in the 1950s said: “We’re geniuses at six, and it’s all downhill from there.” Today, we’re drowning in information, data and stories. Surveillance, secrecy and power dominate our lives in ways never thought of before. Violence has become a cynical, symbolic tool. Future wars will be cyber wars, involving artificial intelligence, social media swarms and lethal drones as part of the mind-boggling mix.

Wounded Marine vet Frank Corcoran, left, and the author in Vietnam, and as a filmmaker being interviewed at the Maine International Film Festival.

Wounded Marine vet Frank Corcoran, left, and the author in Vietnam, and as a filmmaker being interviewed at the Maine International Film Festival.

In 2002, I made a film in Vietnam and motor biked west of Hanoi with two friends, a seriously wounded Marine veteran named Frank Corcoran living and working in Vietnam, the subject of the film, and a Vietnamese woman who did translating. In 1968, 19-year-old Frank had been in Vietnam 45 days when he was seriously shot in the stomach. As he lay bleeding-out under fire, two men crawled out to help him. Between them, they bandage him up — before they were both shot dead off his chest. Frank healed physically but still deals with classic PTSD. In the 84-minute film called Second Time Around, he speaks eloquently about the humanity that drove these more experienced men to save his young life. It’s a tale that will make you shake your head in admiration for the sacrifice and bravery under fire of infantrymen in Vietnam. As Frank emphasizes, their actions had nothing to do with country and patriotism. It was about human love.

As we drove our motorbikes westward out of Hanoi, we really had no idea where we were going, but we trusted and liked the Vietnamese. We ended up in a village talking with a man our age who had been an NVA soldier along the DMZ between North and South Vietnam. In his little store he had a crude tin tank about eight feet high full of fermenting beer that he dispensed from a garden-style faucet sticking out of the bottom of the tank. It was probably the worst beer I’ve ever tasted, but that didn’t seem to matter. It had been a long, hot day and we were all delighted with each other’s company. As we drank his beer and began to get a buzz on, we told stories through our translator about our relative roles in the war. We all agreed that was then; this is now. And now is different. There were no recriminations either way; just a mutual respect and joy in telling stories and laughing together. In the back of our minds, we all knew that, in years past, we would have had to think about killing each other. My friend and I made it clear we were disgusted with our government and its policies, during the war and now. We then learned that this man felt the same way about his government, then and now. He stationed along the DMZ and had been disgusted with some policies the government of the North had initiated there. I concluded it was the North Vietnamese version of what is known in our military as “chicken shit.” The NVA soldiers we were fighting back in the 60s were just as trapped as many of us were; they had their own version of FUBAR: Fucked Up Beyond All Recognition. What our World War Two fathers called SNAFU: Situation Normal, All Fucked Up. We drank more bad beer, toasted each other and cursed all governments. When we left the man’s shop, it was amazing we could stay up on our motorbikes. It had been a wonderful moment of solidarity that transcended the tragic pointlessness of the war.

In exceptional America, we’ve deluded ourselves into thinking that being “ill-used by fate” — what the Vietnamese heroine Thuy Kieu was stoically inured to — is something Americans don’t have to deal with. Faced with difficulty, we take charge and kick some ass. If events aren’t going our way, we fake it and make things up. Then, we drop huge bombs. Or, as the future will have it, we kill people from 12,000 miles away while sitting in an air-conditioned cubicle sipping a Diet Coke. Then, at the end of our eight-hour shift, we can go home to play with our kids and watch TV.

I’m not as naïve as I was 50 years ago on that mountaintop overlooking the Cambodian border in Vietnam. We’re now probably closer to civil war in this country than at any time in modern memory. As a kid sitting atop that huge mountain in the midst of such amazing natural beauty, the Se San River winding through it like a golden snake, I could never have imagined the leadership of America that had sent me there to help kill Vietnamese for no good reason would fail to learn much of anything from the fact. Let’s not delude ourselves: While we didn’t screw things up alone, it’s a fact post-WWII American leadership is profoundly implicated in the current disastrous state of the world. The slow-motion train wrecks of Iraq, Afghanistan and the idea of a Forever War makes me nostalgic for that simple, inebriated meeting with a former enemy soldier west of Hanoi.

A Vietnam vet friend of mine tells me I should apply for PTSD status. Maybe it’s because of my infantryman brother and so many friends who were grunts that I feel I can’t be that messed up. I feel that the corruption that saturates our culture (Jimmy Carter called it a malaise) has become so intense that everybody suffers from war stress. I know Vietnam veterans with serious, diagnosed PTSD serving life-without-parole for murder, while Henry Kissinger is free and considered a statesman. Bill McKibben, the environmentalist leader who founded 350.org, said it well in a Times op-ed following President Trump’s abandonment of the Paris Accords. He cited the “dysfunctional American political process” as the cause of our problem. It isn’t “because [Trump] didn’t take climate change seriously, … [It’s] because he didn’t take civilization seriously.”

We’re being dragged into a Hobbesian world of war in which everybody is pitted against everybody else. We’re no longer imperially hunting the Vietnamese in far-away forests. We’re now living in fear of infuriated people with strapped-on bombs or losers with AR15s unable to cope with being “ill-used by fate.” Leaders like Trump now fight only for themselves and, modelling themselves on successful authoritarians like Vladimir Putin, search out and destroy those weaker and poorer than themselves.

Maybe it’s not too late to learn something from the Vietnamese about resilience, resistance and the survival of a cooperative spirit.

Finally, from The Tale of Kieu:

Roosters crowed at the moon. She walked and walked,

leaving her tracks on the dew-sprinkled bridge.

Deep into the night, along a road unknown,

She braved the wind and weather and went on.

___________________________________________

Click here to go to My Vietnam War, 50 Years Later, PART ONE: “A REMF Way Out In The Front”