Click here to go to My Vietnam War, 50 Years Later, PART TWO: “Memory, Writing and Politics”

A REMF WAY OUT IN THE FRONT

Each of us carried in his heart a separate war which in many ways was totally different . . . we also shared a common sorrow; the immense sorrow of war.

– Bao Ninh, The Sorrow Of War

It’s hard to believe that 50 years ago I was a 19-year-old kid in Vietnam sitting on a mountaintop near the Cambodian border in the forests west of Pleiku trying to locate equally young North Vietnamese radio operators with a piece of WWII RDF equipment I’d been told was obsolete. I was part of a two-man team, working in conjunction with two other two-man teams; our job was to listen for enemy broadcasts, which were sent in coded five-letter groups of Morse code. Sometimes we searched and located random operators. Other times, we’d get an intel lead on when an operator would come up. Using the silver-alloy rotating antenna of the obsolete PRD1, we obtained a bearing that was then plotted on a map; hopefully, the three bearings would provide a tight fix and locate the operator. We’d give the map coordinate to division G2, who would assign some death-dealing operation to search and destroy whatever was on or near the coordinate. Throughout it all, I remained relatively safe, while the men I most respect in this business of war — the mostly drafted infantrymen, or “grunts” — did the dirty work “humping the boonies” with weapons and packs. I went to Vietnam on a troop ship (a rust-bucket named the USNS General Hugh J. Gaffey) in August 1966 with an Army Security Agency company; once we arrived in division base camp in Pleiku, seven of us were assigned to a tactical DF team with, first, the 25th Division, then the 4th Division. I later spent a few months at a cushy strategic DF site in Camrahn Bay.

Aboard the WWII-era USNS Hugh J. Gaffey headed under the Golden Gate to Vietnam, August 1966

Aboard the WWII-era USNS Hugh J. Gaffey headed under the Golden Gate to Vietnam, August 1966

In one operation, our teams hunted down an operator known to us as SOJ. It took us 30 days. Each day, the operator would use a different frequency and call sign; it always amazed us clueless kids that G2 Division Intelligence knew this. Sure enough, at the prescribed time, there he was. First thing, we’d locate our coordinates on the map by sighting on road intersections or hilltops. Our team sergeant inside a box on the back of a three-quarter-ton truck at base camp would plot our bearings and, hopefully, get that tight “fix.” The NVA radio operator we were looking for was attached to what was presumed to be a large dug-in unit HQ; the operator was transmitting to a larger HQ over the Cambodian border. They knew we were looking for him, so every day this operator with a leg-key and a comrade with a bicycle generator would go to a different location at some distance from his unit. Over 30-days, a pattern developed, and G2 figured where the dug-in unit must be. Some combination of long range reconnaissance patrol (LRRP), 105mm or 155mm howitzers, F4 Phantom jets and the ultimate weapon, infantry grunts, located the unit and destroyed it and all the soldiers in it — presumably including my counterpart radio operator, whose Morse key characteristics we had developed a sensitivity to. A large arms cache was discovered. My comrades and I were each given an Army Commendation Medal for the operation.

Today, I actually feel pretty rotten about my part in all this. As I’m wont to do these days, I like to ask anyone who expresses anything positive about the war, can you tell me anything — anything! — that the Vietnamese did against us here in the United States. Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh guerrillas were our ally in World War Two against the Japanese who had driven the colonial French army into its barracks as the French government collapsed and collaborated in Europe. Terrorist acts? Not a hint. Well they were communists, weren’t they? Yes, but they also quoted the US Declaration of Independence at the end of WWII, hoping the US would support their liberation from French colonialism. It was not to be; we supported French re-colonization, which led to 30 years of terrible war on the Vietnamese. And a US retreat based on the war’s ultimate immorality.

I had it pretty good in Vietnam, compared to many in the infantry and other dangerous jobs. My older brother was there during the same time; he was a platoon leader in the 25th infantry. Fortunately, he made it home unscathed. I ran into him once as I and my DF teammate were dropped into a firebase in the saw grass west of Pleiku, a place that looked from the air like a cigar burn in a shag carpet. I’d been there two days, during which we dug and fortified a small bunker against mortars. “I think that’s my brother over there,” I told my comrade, pointing across the LZ. My brother’s infantry company was on what was called “palace guard” protecting the battalion firebase, which featured a 105mm howitzer battery. I stayed there maybe four days and moved on, which was how it went for us. The day after I left, the place was hit. As I look back 50 years, I realize I was a wide-eyed kid who, it feels now, led a lucky, charmed life in Vietnam, always moving from one place to another, never really connecting, then moving again. Always avoiding the bad shit. Sometimes we worked off the back of our jeeps; sometimes we did DF on Armored Personnel Carrier (APC) patrols; sometimes we were dropped off on forest hilltops. So I got around in the midst of the historic conflagration known as The Vietnam War, here, and to the Vietnamese, as The American War.

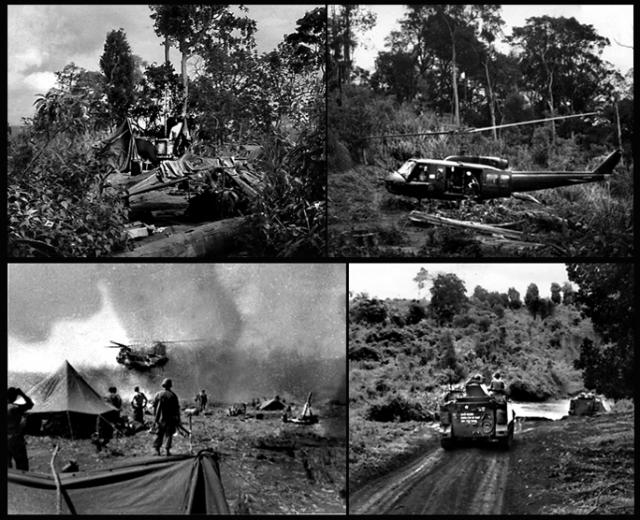

Clockwise from top left: teammate working the PRD1 in front of our tent; hilltop re-supply; an APC direction-finding operation; chinook landing at a firebase and blowing everything silly.

Clockwise from top left: teammate working the PRD1 in front of our tent; hilltop re-supply; an APC direction-finding operation; chinook landing at a firebase and blowing everything silly.

The wildest mission for me was the 10-days I spent on a massive rock outcropping at the top of a huge mountain overlooking the Cambodian border. Hueys would have to hover in an opening in the trees and slowly drop down to put one skid on the huge rock formation thrusting out of the top of the mountain. With the chopper blades spinning like crazy — and a disconcerting red light on the Huey’s dash blaring out RPM! RPM! RPM! — we threw our rifles and DF crap out the door and jumped out after it. Same-same with a second ship of seven grunts assigned to protect our REMF asses — as in, Rear Echelon Mother Fuckers. I once wrote and performed a blues song titled “REMF Way Out In The Front” based on this 10-day episode. Of course, for the seven grunts, it was like R&R to catch up on their sleep. Fortunately, the only “contact” we had was a short 105mm artillery round that hit the top of one of the trees, sending shrapnel down on us. One of the grunts got a piece of hot steel in his hip and was medivaced out.

Our protectors set out trip flares around the base of the rock. One night one went off, scaring the hell outa me. We concluded it was an animal; I imagined a very surprised roaming tiger tripping the flare. Sometimes, we’d hear firefights going on at the base of the mountain, but there didn’t seem much chance the NVA would come up the mountain for us. One day, F4 Phantoms were screaming low over our heads; they’d drop and roar down the side of the mountain, firing 40mm guns at the NVA below us. We began to hear noises like rustling leaves in the woods below us. Holy shit! They’re coming up the mountain! We all jacked our weapons and got ready, laying down on the rock, pointing them down into the forest below, waiting for Charlie to break through the trees fleeing from the F4’s guns. We waited and we waited. Each time an F4 came over we’d hear the rustling again. Eventually, we figured out the noise was empty shell casings hitting the trees and the ground.

I went back to my duties listening on earphones to Morse code and getting bearings on NVA radio operators. But in those minutes waiting for Vietnamese men to appear out of the forest, I realized I was capable and willing to shoot a human being. If a Vietnamese broke through the brush, I was ready to shoot him. Of course, I still had no clue why I was there on that mountaintop doing what I was doing. The incident helped me understood what drives a war like Vietnam: My government decided to invade Vietnam, which meant once I got there people wanted to kill me — unless I or my comrades killed them first.

Most of the time on that incredible rock amounted to amusing myself from boredom. I remember reading a dog-eared copy of Joseph Heller’s Catch 22 I’d found laying around. I’d also climb down from the rock and walk a ways into the woods, where I’d sit on a log and just listen and look around, amazed that I was on a huge mountaintop along the Cambodian border in the middle of a bloody warzone. The forest along the ridgeline atop that mountain felt peaceful. I’d hear little critters scurrying around. I saw a black flying monkey soar from one tree to another. I ran into lizards and peculiar insects. I saw a strange-headed, very large predator bird gliding over us and riding the wind currents. It was not until the 1990s and a reading of The Sorrow Of War, the magnificent novel by Boa Ninh, that I realized, for the Vietnamese, that forest was animated by spirits and ghosts. Boa Ninh’s character Kien speaks hauntingly of spirits inhabiting the forests of the Central Highlands, something I was not aware of, being a foreigner from 12,000 miles away. Or maybe the spirits just left me alone, figuring I was harmless. Here’s how Boa Ninh describes a forest from the point of view of the 27th NVA Battalion:

“It was here, at the end of the dry season of 1969 that his 27th Battalion was surrounded and almost totally wiped out. Ten men survived from the Lost Battalion after fierce, horrible, barbarous fighting. … [Ghosts] were born in that deadly defeat. They were still loose, wandering in every corner and bush in the jungle, drifting along the stream, refusing to depart for the Other World. From then on it was called the Jungle of Screaming Souls. Just hearing the name whispered was enough to send chills down the spine.”

Like Boa Ninh has done with his American War, I’ve written fiction about my Vietnam War. My fiction was two short stories in Penthouse magazine in the late 1970s. “Polyorifice Enterprises” was modeled on the black humor of Catch 22 and satirized the prostitution that was epidemic in places like Pleiku. For security and health reasons, the Fourth Division supervised whorehouses just outside the base camp gate. Everything a horny 19-year-old American soldier wanted was catered to by entrepreneurial elements among the South Vietnamese. We were young American males feeling great power as part of a massive army, and we had money burning holes in our jungle fatigue pockets. Young peasant girls were an attractive commodity to be exploited and, sometimes, abused by US soldiers. It’s worth noting that the most famous work of literature in Vietnamese — the narrative poem The Tale of Kieu written by scholar Nguyen Du around 1810 — is about a young woman who becomes a prostitute to save her family from ruin in a period of war lord rule. She eventually becomes a guerrilla chieftain and prevails. The first stanza of the poem ends with these lines:

One watches things that makes one sick at heart.

This is the law: no gain without loss,

and Heaven hurts fair women for sheer spite.

Later, a character says this of the protagonist, Thuy Kieu.

She is a woman much ill-used by fate!

But then it’s nothing new beneath the sun.

A poetic sense of stoicism and the dignity of life in times of disaster and trial are the core of this great work. When I came home from Vietnam, I began haunting used bookstores, reading things like The Tale of Kieu and books like Street Without Joy by Bernard Fall and his other books on the French war and the transition to the American war. Slowly, I began to understand what I’d been floundering around as a charmed youth. I wanted to learn more; I began to feel a sense of mission to show how and why the war had been very wrong and never should have happened. But telling that story in mainstream American culture is Sisyphian.

For some reason that’s worth pondering, the Vietnamese like Americans. In the spirit of Kieu, they seem wise enough to know, following a war — and they’ve had many besides the one with us — there’s little benefit to nursing vengeance and holding a grudge. It’s time to move on, the pragmatic essence of forgiveness. Maybe it’s because they’re a small nation with real survival issues, while, in our case, we’re a huge, imperialistic nation with affluence and domination as a goal. Plus, we don’t lose wars; it’s imprinted in our DNA. My poet friend Bill Ehrhart, a wounded Marine vet, has a short poem that goes right to my heart every time I read it:

Do they think of me now

in those strange Asian villages

where nothing ever seemed

quite human

but myself

and my few grim friends

moving through them

hunched

in lines?

When they tell stories to their children

of the evil

that awaits misbehavior,

is it me they conjure?

Click here to go to My Vietnam War, 50 Years Later, PART TWO: “Memory, Writing and Politics”