Following a brief hearing in Philadelphia yesterday, Court of Common Pleas Judge Leon Tucker, learning that the Philadelphia District Attorney’s office had thus far failed find and turn over, in response to his earlier order, any documents showing a role by former District Attorney Ron Castille regarding the department’s handling of an appeal by then death-row inmate Mumia Abu-Jamal, adjourned the hearing until Aug. 30. The judge acted to give Abu-Jamal’s attorneys time to depose a former DA employee about a still unlocated memo apparently composed by her for then DA Castile concerning Abu-Jamal’s case.

Later, Tracey Kavanagh, the attorney from the DA’s office who represented the DA’s office at the hearing, stood outside on the sidewalk outside the Criminal Justice Center amidst a scrum of TV cameras and said, “We haven’t found any evidence so far that Judge Castille played any role as DA in Abu-Jamal’s appeal of his conviction. It was just a run-of-the-mill appeals process.”

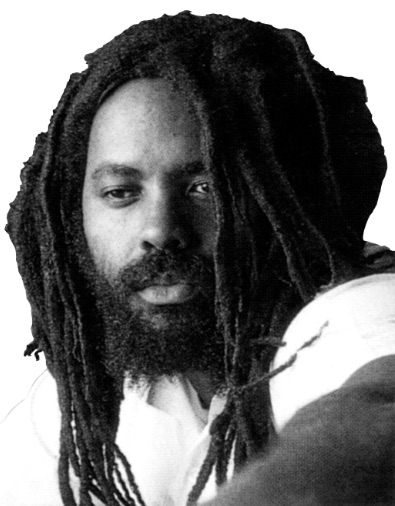

If one wanted evidence of how absurd Kavanagh’s assertion was — that the appeal of a 1982 murder conviction and death sentence for the slaying of a white police officer by one of the city’s leading African-American journalists, himself police critic and former member of the city’s Black Panther Party, was anything but a prime political concern for District Attorney Castille, whose office had the responsibility of preventing any challenge to sentence — all one had to do was try to get into the courtroom on Monday.

I tried. Some 100 or so supporters of Abu-Jamal had shown up at 7:30 in the morning outside the county courthouse on Filbert St. near City Hall to protest his continued incarceration. They then lined up when doors opened to shuffle their way through security in the court building and then up to the 11th floor to line up again at the entrance to the small courtroom Number 1108. By the time I got there, along with many other journalists and interested parties, we found ourselves unable to get into the courtroom. But a lot of police officers, even those arriving later than us, had no trouble gaining entry.

The sheriff’s deputy standing guard in her flak vest at the courtroom entrance, and another guarding a side entrance to the courtroom, saw to it that plenty of cops in uniform, fully equipped with their sidearms and tasers, were allowed inside to sit in the spectator benches and put pressure on the judge and the attorneys from the DA’s office. When anyone left the courtroom, the sheriff controlling access still barred other citizens waiting in the hallway from replacing them. But if a cop left the courtroom, another would freely enter. Over at the side door, other officers were also occasionally being allowed to enter. Clearly space was being reserved in the courtroom for police at this hearing.

In general, police officers are not supposed to wear their uniforms when they are off duty, although in some cities they are allowed to do so if they are doing some security job where the department has specifically authorized them to wear the uniform. Otherwise no. But here they were — even a burly Highway Patrol motorcycle cop decked out ostentatiously in his knee-high leather boots, motorcycle jacket, and ‘30s-era aerodynamic motorcycle officer’s cap.

So that raises the question of who dispatched these officers to sit in the courtroom and to hang out in the hallway. Philly cops don’t provide court security, a task assigned to Sheriff’s Department. So either the Philly Police Department sent them over and they were there on official duty, collecting paychecks to hang around in the hall or sit in the courtroom looking grim and angry, or they were organized by the Fraternal Order of Police, the police union which, like Ahab pursuing his White Whale, has been dedicated to having Abu-Jamal executed or, since 2011 when his death sentence was finally tossed out on Constitutional grounds, to seeing that he never gets out of jail.

Of course, if individual cops, or even a group of cops, want to go sit in a courtroom as citizens to observe the proceedings or to provide moral support to the slain Officer Daniel Faulkner’s widow (who was also in attendance), they can, like any other citizen. But that’s not what was happening here. Rather, these cops were being allowed to come into the court in their uniforms, either illegally if they were off duty, or at taxpayer expense if they were officially on the job (though off their beats), and they were being given special consideration in getting seats.

That’s not equal justice at work. But it is evidence that this case, even today, long after Ron Castille moved on from District Attorney to State Supreme Court Judge and ultimately to Chief Justice of the State Supreme Court, where he helped to reject Abu-Jamal’s appeal of his conviction, refusing to recuse himself despite his obvious role as DA from 1986-91 in overseeing the opposition to that appeal, (Castille was elected to the state’s Supreme Court in 1991, and retired as Chief Justice in 2014.)

This is important because back in 2016, in a case called Williams vs. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the US Supreme Court ruled that a Pennsylvania death-row defendant, Terry Williams, deserved a new sentencing hearing because Castille, who as DA had supervised the prosecution of his case when Williams was just a 17-year-old being tried as an adult for murder, later ruled on his appeal as a Supreme Court Judge — voting as part of the court majority to restore Williams’ death penalty after it had been revoked. Now Abu-Jamal’s legal team is arguing that the Williams case precedent should also apply to both Abu-Jamal and a number of other cases where Castille corruptly played the role of both prosecutor or supervisory prosecutor and of appellate judge. They argue that Abu-Jamal should get a whole new round of appeals at least back to his initial Post Conviction Relief Act hearing in 1995.

If he can prove that case to the judge’s satisfaction, Abu-Jamal could restart his appeals with a new PCRA, where new evidence of his innocence could be presented, possibly leading to an overturning of his conviction or to a new trial.

The throng of cops sent to sit that courtroom Monday, all committed to seeing to it that doesn’t happen, give the lie to the Assistant DA’s curb-side assertion that during Castille’s tenure as District Attorney, Abu-Jamal’s appeal was just a “run-of-the-mill” affair and nothing that Castille as DA would have bothered himself with.

Sure he wouldn’t have. If the case is still such a hot-button issue today, 37 years after the Faulkner shooting and 36 years after Abu-Jamal’s conviction, it certainly was a hot issue in the four to eight years after the trial that Castile was serving as Philly’s DA.

DAVE LINDORFF is author of Killing Time: An Investigation into the Death-Row Case of Mumia Abu-Jamal (Common Courage Press, 2003)