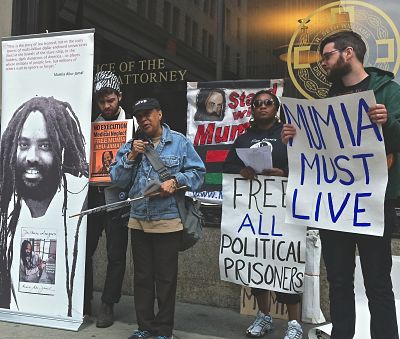

Pam Africa (with mic) and Abu-Jamal supporters protest outside office of Philadelpia's DA. -LBWPhoto

Pam Africa (with mic) and Abu-Jamal supporters protest outside office of Philadelpia's DA. -LBWPhoto

In July 1987 Philadelphia’s then District Attorney lashed out at local judges in an unusual verbal assault where that DA castigated what he said was the “historic” practice of judges in Pennsylvania’s largest city to acquit police officers in cases where evidence clearly showed officers engaged in “egregious” brutality.

That DA, Ronald Castille, told a reporter that, “I know the judges will bend over backwards to use whatever reasons they can to throw a case out against a police officer.”

Eleven years after Castille’s outburst against pro-police bias by some Philadelphia judges, Castille engaged in pro-police bias as a member of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania.

Castille’s 1998 bias act occurred when he participated in the Pa Supreme Court’s rejection of a critical appeal in the case of Mumia Abu-Jamal – the Philadelphia journalist convicted in 1982 and sentenced to death for killing a Philly cop during a trial tainted by a pro-police judge.

Abu-Jamal’s conviction is condemned internationally as a gross miscarriage of justice engineered by police, prosecutors and the trial judge.

Condemnation is also leveled at the appellate process that has consistently rejected extraordinary evidence of Abu-Jamal’s innocence and documentation of multiple misconduct by authorities. An Amnesty International report on the Abu-Jamal case, released in February 2000, criticized the “appearance of judicial bias during appellate review…”

Ronald Castille, who rose to the rank of Chief Justice of Pa’s Supreme Court, is currently at the center of Abu-Jamal’s latest appeal for a new trial that claims Castille violated judicial ethics by his Pa Supreme Court participation in Abu-Jamal’s appeal.

That appeal also contends Castille’s actions in the Abu-Jamal case violates the dictates of a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that blasted Castille for ruling on a case as a supreme court justice that he handled while DA.

Pennsylvania’s judicial conduct code states judges must recuse themselves from cases where their impartiality is reasonable questioned and recuse from cases where the judge knows facts about that case due to former employment with a government agency like District Attorney. Castille, as DA, opposed appeals by Abu-Jamal, signing the DA documents submitted in court.

Castille and the current Philadelphia District Attorney, deny any improprieties against Abu-Jamal. Castille, who campaigned for DA and the Supreme Court as a hands-on manager, contends he signed anti-Abu-Jamal appeals as DA simply as a hands-off administrator.

Castille, for example, claimed he signed DA documents that opposed Abu-Jamal appeals without reading those DA documents thus he knew nothing about specifics of Abu-Jamal’s case when he rejected Abu-Jamal’s appeals to the Pa Supreme Court.

The posture that Castille as District Attorney knew absolutely nothing about the Abu-Jamal case – the most controversial police murder case in Philadelphia’s history – defies law, logic and common sense.

Four years before Castille participated in the Pa Supreme Court’s 1998 rejection of an Abu-Jamal appeal, a former top aide to DA Castille told a Philadelphia reporter that his old boss “was involved in death penalty cases” and Castille was also involved in “high-profile cases.”

While that aide to Castille did not specifically mention the Abu-Jamal case during that 1994 interview, the Abu-Jamal case was definitely high profile and it was then a death penalty case. (Many years later Abu-Jamal’s sentence was shifted from death to life in prison without parole.)

Back in 1987, one of the three courtroom acquittals of brutal police that sparked Castille’s ire involved a policeman fired for choking a handcuffed suspect inside a hospital emergency room that forced hospital personnel to restrain that officer.

Before that emergency room incident, fired policeman Gary Wakshul viciously pummeled that suspect outside a department store and then beat him again inside a police station. But a Philadelphia judge ruled Wakshul’s multiple acts of brutality were “not a crime.”

Following that acquittal, Philadelphia’s police union, the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP), tried unsuccessfully to have Wakshul reinstated to his police job. Wakshul eventually landed a position with Philadelphia’s court system – the entity with the judges Castille had criticized for pro-police bias.

Wakshul, a few years before that emergency room beating incident, played a pivotal role in the conviction of Abu-Jamal. Wakshul was one of two policemen who claimed they heard Abu-Jamal confess to killing Officer Daniel Faulkner.

But Wakshul’s claim of an Abu-Jamal confession contained big problems…problems that courts (state and federal) cavalierly dismissed.

Wakshul didn’t recall hearing that alleged confession until weeks after Faukner’s murder. Wakshul suddenly remembered the alleged confession during an investigation into an abuse complaint filed by Abu-Jamal that charged police brutally beat him at the site of his arrest and inside a hospital emergency room.

Wakshul told investigators that he dismissed the confession when he heard it shortly after Faulkner’s death because when he heard it he didn’t think such a confession was important. Yet, less than ninety minutes after the 12/9/1981 fatal shooting of Faulkner, Wakshul filed an official police report where he declared Abu-Jamal “made no comments.”

During Abu-Jamal’s 1995 appeal the Pa Supreme Court, inclusive of Castille, permitted the biased judge who presided over Abu-Jamal’s 1982 trial (the infamous Albert Sabo) to preside. That high court sanctioned Sabo’s appeal involvement even though one major appeal item was the bias of Sabo, who was a former member of Philadelphia’s police union, the FOP.

One of Abu-Jamal's sons – Jamal – (right) at street naming ceremony in a suburb of Paris. -LBWPhoto

One of Abu-Jamal's sons – Jamal – (right) at street naming ceremony in a suburb of Paris. -LBWPhoto

Sabo’s bias during that 1995 appeal hearing was so outrageous numerous journalists detailed that bias. Sabo’s conduct even outraged Philadelphia mainstream journalists who traditionally rejected claims that authorities violated Abu-Jamal’s fair trial rights. Philadelphia journalists, for example, wrote sharp editorials and scathing commentary condemning Sabo’s bias.

However, Castille and his state Supreme Court confederates dismissed the journalists’ confirmed evidence of Sabo’s bias with the haughty contention that the “opinions of a handful of journalists do not persuade us” that Sabo showed “an inability to preside impartially.”

Judges are supposed to use precise language in their rulings. The word ‘handful’ means a ‘small’ number of people. There were nearly two-dozen journalists on just the editorial boards of both Philadelphia daily newspapers that castigated Sabo’s bias in 1995. Two dozen is clearly more than a ‘small’ number of people.

When the Pa Supreme Court in 1998 upheld Sabo’s rejection of Abu-Jamal’s 1995 appeal, Castille issued a document denying Abu-Jamal’s request that he recuse himself. Castille declared no need for recusal on the specious contention that he knew no facts of that appeal/case as DA.

Amazingly Castille also employed another defense – one that cast a long shadow of impropriety that federal judges have ignored.

Castille asserted absurdly that it was unfair to cite his receipt of financial and political support from police groups across Pennsylvania, particularly his many endorsements from Philadelphia’s FOP, when four other members of the Pa Supreme Court had received electoral support from “the very same FOP which endorsed me.”

The fact that five members of a seven member Supreme Court received financial and political support from the FOP organization that was an aggressive advocate for Abu-Jamal’s execution undermined both the ethical mandate appearance of impartiality by judges and the reality of fairness allegedly underlying America’s vaulted concept of justice.

Earlier this year Castille, now retired from the Pa Supreme Court, told a reporter that he didn’t recuse himself from contentious cases arising from his DA tenure because he was never asked to recuse – a clearly false statement regarding the Abu-Jamal case. Philadelphia’s current DA admits that Castille’s statement is wrong.

Current Philadelphia DA Larry Krasner’s fight against this latest appeal by Abu-Jamal, is criticized by many as soiling Krasner claim to fame as a reformer and defender of justice.