Sean Hannity grinned and seemed to bounce up and down like he was plugged into an electric socket as he ripped into Hugo Chavez, the Venezuelan president who had just succumbed to cancer. Hannity was joined in his death gloat by Michelle Malkin, one of the more delightfully odious voices on the far right.

They had no interest at all to understand who this dead guy had actually been in life. Their escalating duet was so full of hate-fueled fantasy it was laughable. The Venezuela under Chavez that Malkin described through her trademark snarling lips was a vision of North Korea, not a place in South America with Carter-approved free elections.

Three faces of Hugo Chavez, with an image of the beloved South American liberator Simon Bolivar

Three faces of Hugo Chavez, with an image of the beloved South American liberator Simon Bolivar

The mainstream US media was not much better. A Time magazine obit was headlined: “Death of a Demagogue.” NBC’s Brian Williams, the picture of perfect middle-brow authority, put it this way: “The words ‘Venezuelan strongman’ so often preceded his name, and for good reason.” Williams ended his obit by saying, “All this matters a lot to the US, since Venezuela sits on top of a lot of oil and that’s how this now gets interesting for the United States.”

Williams’ assumptions were rooted in the much-reinforced, traditional North American view of las Americas that reduces poor nations south of the border — except of course those with lots of oil — to Henry Kissinger’s status as easily-ignored because they aren’t part of something called “the arc of history,” which strangely seemed to coincide with Europe and the United States.

A March 7th New York Times editorial presented a schoolbook example of North American hypocrisy as it listed all the various imperfections that existed in Venezuela’s governing reality under Chavez. “His legacy is strained by the undermining of democratic institutions.” No mention, of course, of Florida-2000 and the “undermining of democracy” in the US that arguably led to two disastrous wars and an economy run into a ditch by Wall Street Ponzi thieves. The Times also noted that in Venezuela there were “shocking levels of corruption” and “billions have been squandered through inept and careless management.” I guess, in North America, corruption is just too big to report when you’re evaluating a South American leftist who has just kicked the bucket.

But there was hope for the Times. Across from its editorial, there was an op-ed by former Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva — a former union leader popularly known as Lula. Unlike the average gringo caught in the imperial behemoth to the North, Lula was able to look at Chavez, the man and the legacy, with a longer, more balanced view.

“History will affirm, justifiably, the role Hugo Chavez played in the integration of Latin America, and the significance of his 14-year presidency to the poor people of Venezuela.”

Lula did not preclude that there is room for fair-minded criticism of Hugo Chavez, given the man was imperfect and had feet of clay. The point was to look at him through the eyes of North, Central and South American hemispheric history versus the short-term and often infantile ideological visions of North American critics.

In North America these days, assumptions about the free-market and profit-motive-as-god rule our corporate airways so thoroughly it’s hard for the average North American to imagine what it’s like for a politico to actually identify with the poor and the powerless. Here, for a mainstream media personality to utter a kind word about the dead Hugo Chavez’s legacy could mean career suicide.

The idea that poor people in union with each other had just as much right to claim the benefits of the oil in the ground below them as those people with access to executive jets who were rich and powerful … well, it was just a bit too Marxist. And as we all know, anyone who has ever found any intelligence in Marxian analysis must eat their young.

In the same vein, when it came to Hugo Chavez it was off limits to even consider the Hegelian idea of history moving in a dialectical fashion. I think this is what Lula meant when he wrote “History will affirm” Hugo Chavez. The Hegelian thesis would be the world of Venezuela and South America before Chavez, and the Chavez years would be the anti-thesis. The future will be the synthesis, an unfolding reality that cannot avoid the powerful influence of Hugo Chavez.

I can see Michelle Malkin’s lips pulling back into a snarl at the mention of these things. But the real arc of history is greater than knuckleheads like Malkin and Hannity — even his eminence Henry Kissinger. In the end, thanks in large part to Hugo Chavez, there can be no turning back the clock in Venezuela and South America.

At the Birth of Empire

I recently watched the three-hour cinema epic Rough Riders, written and directed by the right-wing John Milius who is notorious for the original Red Dawn and for co-writing Dirty Harry and Apocalypse Now. Tom Berenger plays Theodore Roosevelt as he wills himself from a bureaucratic assistant secretary of the Navy into a blood and guts commander of men he compares with the rough, bloody hordes of Ghengis Khan. The film is as much a paean to the warrior myth as it is a loving evocation of the birth of 20th century American imperialism.

Director John Milius and Tom Berenger as Teddy Roosevelt after taking the San Juan Heights

Director John Milius and Tom Berenger as Teddy Roosevelt after taking the San Juan Heights

Personally, I wish the film had been directed by Sam Peckinpah, who made the ultimate film masterpiece of violent, bloody male bonding. But, then, The Wild Bunch is actually subversive; its four protagonists are bank robbers in 1913 being made obsolete by the encroaching modern world. They, of course, choose to go out in a blaze of martial glory.

Rough Riders also ends in a blaze of glory, but its protagonists, led by Roosevelt and a carefully arranged cast of all classes and races, aren’t running from the encroaching modern world — they represent it.

For Roosevelt, 1898 is far from a dying world. In a strange and interesting way, Peckinpah’s Wild Bunch protagonists — honor-driven, independent, Mexican-peasant-loving US bandits — are the antagonists of Milius’ Rough Riders, who represent the birth-pangs of the Military Industrial Complex Dwight Eisenhower warned American citizens of in 1961.

Milius’ Roosevelt saga is the story of a nation so full of itself it seeks and even provokes war as an outlet for its expansive manhood. After the battle for the San Juan Heights in Cuba, the triumphant Roosevelt is shown exhausted and saddened by all the death. An older black man — used earlier by Milius as a Greek chorus — says to him, “It’s all right, Colonel.” Roosevelt looks at him and replies: “It will never be the same.”

Milius then whacks us up side the head with a hammer. Behind Roosevelt, a large US flag waves in the wind. Behind the waving Old Glory, shown intermittently and accumulating in our minds as the scene unfolds, is an advertisement for cigars painted on the side of a water tank that spells out EMPIRE.

Get it? We’re at the birth of Pax Americana, the bringing of order to the benighted parts of the world by the barrel of a gun if necessary. In The War Lovers, Evan Thomas makes it clear how much Roosevelt and friends like Henry Cabot Lodge sought war as a means to save American manhood from neurasthenic torpor. War itself was the goal; it didn’t really matter to Roosevelt against whom it was fought. Cuba became the war object because the Spanish Empire was weak and vulnerable. William Randolph Hearst and The New York Journal did the rest. And as we know in the Philippines, once the Spanish were dispatched, we turned against the very insurgents we had nominally come to liberate. We first used waterboarding against these insurgents.

Twelve years after Cuba in 1910, ex-President Roosevelt published a small book of essays entitled American Problems. One of the essays was called “The Management of Small States Which Are Unable to Manage Themselves.” In it he writes, when managing a backward state (like the Philippines), “It is probably better for the State concerned to be under the control of a single Power, even though this Power has not high ideals, rather than under the control of three or four Powers which may possess high ideals.”

Why? Because three or four Powers might fight amongst themselves over the spoils. Better to keep one’s boastful martial focus on the poor little brown people.

Hugo Chavez and the Endgame of Empire

No one understood all this better than Hugo Chavez. As a young army officer with peasant roots, he had been sent out to round up or kill indigenous guerrillas. He soon began to question the assumptions and the context behind those orders. He shared his doubts with other officers. The rest is history: A failed but not forgotten 1992 coup, a couple years in prison, then election to the presidency of Venezuela. Not bad for a poor kid of mixed Native American, African and European roots.

In the US imperialism business, Marine General Smedley Butler played a major role in the Philippines, Central America and Haiti. Like Chavez, he underwent a complete reevaluation of his role, to the point he saw his former self as “a gangster for the Brown Brothers Bank in New York.” “I could have taught Al Capone a thing or two,” he wrote in his famous book called War Is a Racket.

This imperial “racket” often focused on putting down democratic reform movements. There was the 1954 coup in Guatemala that brought in General Castillo Armas and decades of horrific repression; a 1971 coup in Bolivia sponsored the brute General Hugo Banzer; and a Kissinger-planned coup in Chile in 1973 murdered elected President Salvador Allende and gave Chileans General Augusto Pinochet and years of bloody repression. And let’s not forget the 1980s Contra War in Nicaragua or, briefly, the failed Venezuela coup of 2002, which lasted two days and ended with an even more wised-up Chavez returning to office with a vengeance. It was clear to everyone the Bush Administration was up to its neck in that one.

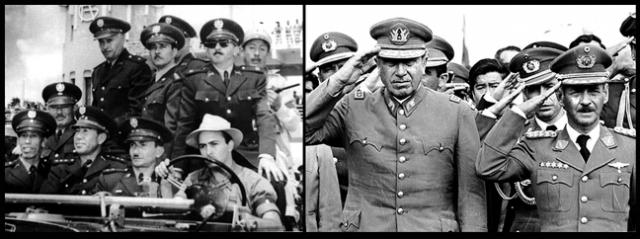

Carlos Castillo Armas next to CIA driver, Guatemala ’54; Chilean Augusto Pinochet, left, and Bolivian Hugo Banzer

Carlos Castillo Armas next to CIA driver, Guatemala ’54; Chilean Augusto Pinochet, left, and Bolivian Hugo Banzer

To bring things up to date, there was the 2009 coup in Honduras, noted for the especially weasel-like posture taken by the Obama administration. During the Contra War, Honduras had been jokingly known as the “aircraft carrier Honduras” due to how the US exploited it vis-à-vis Sandinista Nicaragua. The 2009 coup resulted in two things: one, a wave of murderous repression that still rules, and two, a steady growth of US military bases in the name of the Drug War — now fully linked with the War On Terror.

Daniel Ortega, the president of Nicaragua and a top Sandinista in the 1980s, was once asked why the Sandinistas were so determined to arm themselves. His answer was profound. Referring to the 1954 coup in Guatemala, the 1973 coup in Chile and all the rest, Ortega said, “We’re not interested in post-mortem solidarity.” Both those CIA-supported coups were widely criticized as un-democratic after the fact.

More than anything, this savvy, defensive frame of mind characterizes the defiant, macho anti-Americanism of a Hugo Chavez. It’s ironic that Chavez’s masculine spirit — so devoted to action over reflection — is not unlike what Teddy Roosevelt preached. It’s just on the defensive side of the imperial equation, versus being the aggressor. It took about 100 years for it to come to maturity — as in, what goes around, comes around.

Norman Mailer called George W. Bush a “flag conservative.” Like Teddy Roosevelt, he was a blueblood male in his own way obsessed with the idea of aggressive expansive Empire as a way to save his vision of a troubled, floundering America.

“Flag conservatives truly believe America is not only fit to run the world but it must,” Mailer wrote in 2003. “Without a commitment to Empire, the country will go down the drain.”

Back in 1896, Roosevelt and Cabot Lodge lobbied their neurasthenia-obsessed Republican hearts out for the saving power of manly war. The question now in such circles is can the US still cut the imperial mustard? Better yet, should it still try? Or should it give the lure of Empire up for the sake of the Republic’s soul and survival?

Mailer again: “Patriotism in a country that’s failing has a logical tendency to turn fascist.”

The knuckleheads on the right fantasize a return to the days of John Milius’ Teddy Roosevelt charging up the San Juan Heights to save American manhood from the mugwumps of indecision. But we now live on the backside of Roosevelt’s Empire. Thanks to powerful historical figures like the South American Hugo Chavez, the glory days of bully imperial adventures are waning. As Mailer suggested, for the United States, in the future it’s either humility or it’s fascism. And we know what the knuckleheads want.

So in the annals of imperialism and South American history, all there is to say is: Hugo Chavez — Presente! History will show he was a great American.