Jason Hall, the screenwriter who wrote the script for the Clint Eastwood blockbuster American Sniper, a well-made piece of hagiographic cinema based on a memoir by Chris Kyle, has made what feels like a corrective on the subject. This time, he’s both writer and director of a film that reportedly was initially slated to be directed by Hollywood giant Stephen Spielberg, with Hall as scriptwriter. Whatever inside Hollywood deal-making went down, Hall’s efforts have resulted in a beautiful film. There’s nothing fancy, large or loud about this film. There are no special effects that you notice. It doesn’t traffic in heroics at all. It just feels real.

While it’s a very different kind of movie, in a way it’s The Best Years Of Our Lives, the great 1946 movie about soldiers returning home from World War Two, translated into the language of Post-9/11 Perennial War. This ain’t your dad’s or your grandad’s war; this is warfare of political choice with a professional, volunteer army and the very human complications that come naturally in the wake of such wars.

Adam Schumann (as actor); Miles Teller (as Schumann) and Beulah Koale (as Solo) waiting at the VA

Adam Schumann (as actor); Miles Teller (as Schumann) and Beulah Koale (as Solo) waiting at the VA

Matt Zoller Seitz from Ebert.com, describes the film this way:

The film “has been written, shot, edited and acted in such an intimate and unobtrusive way that the result feels like a throwback to an earlier era of American mainstream filmmaking, when it was still possible to base a handsomely produced feature film around observed behavior, and not feel obligated to safeguard against viewer boredom by shoehorning extra melodrama or contrived genre-movie elements into the mix.”

First off, the title — Thank You For Your Service — is meant ironically. The story began as a non-fiction book by Washington Post reporter David Finkel, who was awarded a MacArthur “genius” grant for his work. As an embedded reporter on the war in Iraq, he wrote an earlier book called The Good Soldiers. He was moved to write the second book when he began to understand how difficult it was for the soldiers he got to know writing the first book when they returned home from the war. Basically, the story is what happens to Sergeant Adam Schumann and two of his unit-mates when they return to the US and leave the Army. Miles Teller plays Staff Sergeant Schumann and Samoan actor Beulah Koale plays the real-life Samoan character SP4 Tausolo Aieti. Both are excellent in the roles. The real Adam Schumann has a small role in the film.

Since it’s a story of the aftermath of war, Hall doesn’t waste time in basic training and the usual preliminaries. The opening scene is like being hit in the face with a shovel. Thus, it sticks with you, which, metaphorically, is the point of the film. Trauma is caused by horrific things that come out of nowhere. As human beings, people don’t perform as perfectly as they would, in retrospect, hope. In a life-and-death context where things unfold in milliseconds, there’s a lot there to haunt the thinking/feeling process, sometimes for the rest of one’s life. And here’s the kicker, no one can really understand. Wives, girl-friends, relatives, friends; they may mean well, but they often just don’t get it. Brothers-in-arms can understand because they’ve gone through their own versions of the same kind of trauma. As young, mostly male soldiers, there’s the constant fear of showing weakness. The result can be explosive; it can turn inward as self-destructive behavior and suicide or outward as aggression and violence.

In a theme that interests me, this film very much comes down on the Eros side of the opposing instincts of Eros (the Life Instinct) versus Thanatos (the Death Instinct). These were designated by Sigmund Freud between the world wars when he became concerned about the rise of violence and fascism in Europe. In his thinking, culture can become besotted and addicted to Thanatos, to the point it becomes self-destructive. The reason I like the Eros/Thanatos continuum, is that it’s useful as a means to discuss violence and culture. To me, Hall and Eastwood’s film American Sniper leaned toward Thanatos and the Death Instinct. The real Chris Kyle, a master sniper, kills lots of Iraqis and, in the end (in life and in the film), is murdered by a man immersed in weaponry and, specifically, the gun-range business Kyle ran in Texas. By contrast, in this film — Thank You For Your Service — the Life Instinct, Eros, wins hands down.

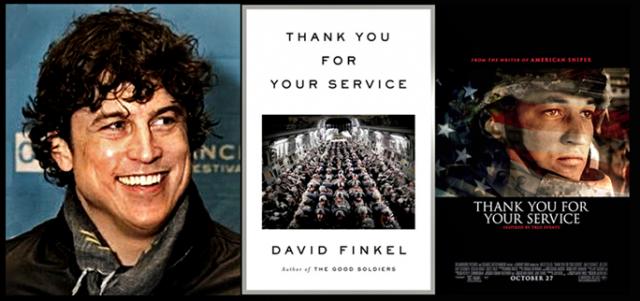

Writer/Director Jason Hall, Finkel's non-fiction book and the movie poster

Writer/Director Jason Hall, Finkel's non-fiction book and the movie poster

The Veterans Administration and the top brass don’t come off well in Hall’s film. In one scene back home, a full-bird colonel is the sort of military blowhard Jonathon Winters, a veteran, loved to skewer as Colonel Robert Winglow. “All right, men, don’t worry, I’m 5000 yards behind you on this hill. I have you in the long lenses. Forward, men!” As for the VA, the image is mixed. The film emphasizes the fact that US tax-payer-funded, war-making priorities are heavily front-loaded. There’s plenty of resources devoted to killing and blowing things up, but not so much — certainly not what’s needed these days of multiple deployments — to address the silent, hidden, long-term wounds of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI). The incredible fact that an average of 22 veterans a day commit suicide hovers over this film.

The cultural question that interests me is whether the American movie-going audience has been corrupted by — and become addicted to — the post-9/11, mythic demand for military heroes in conjunction with seeing special effects as normal. Without these kinds of life-enhancing narrative effects, are movie audiences bored? As Seitz put it, above, do filmmakers need to “shoehorn extra melodrama or contrived genre-movie elements into the mix”? Then you have to ask, does the average American want to know what it’s actually like to come home after being thrown into intimately violent situations like the ones Adam Schumann lived through? Or do they want to wave the flag and have couch-potato thrills? Can a good-hearted film that tells a simple, poignant story like this without resorting to hero-worship or melodramatics make it in the free market, money-obsessed world of Hollywood culture. That culture is now expelling the producer Harvey Weinstein as a pariah. Is this a sign of reform and change? It will be interesting to see if this movie (without loudness and special effects) can make money. My wife and I went to a suburban multiplex on Halloween night and watched it with two other people kn the theater. Money as the final arbiter of value has become a sickness in American politics and culture. As our most vocal cultural patriots love to assure us, men like Adam Schumann fought in Iraq for our freedom to thrive in such a market economy. In this sense, freedom is not free. You have to buy it or you fight for it. It’s interesting that the film ends with a dirge by Bruce Springstein and the enigmatic (ironic?) lyric, “Freedom comes from the barrel of a gun.”

This film is powerful because it’s honest and it’s simply told. It’s about ordinary, good people in very difficult but real situations. If a culture chooses militarism as an answer to so many of its problems — that is, to get Freudian about it — if a culture by choice or default pursues the Death Instinct at the expense of the Life Instinct, self-destruction is a very real unanticipated consequence. I think what Freud was saying, like the Adam Schumanns of the world, that Cultures and Societies can suffer Post Traumatic Stress too. Just like individual human beings, they can explode inwardly and outwardly too.