Depending on how you look at it, lawyers for Mumia Abu-Jamal, the Philadelphia journalist and political prisoner serving a life sentence in a Pennsylvania prison after a controverial 1982 conviction for killing a white Philadelphia police officer, won a huge victory, lost big or maybe won and will win again soon.

His victory, a finding issued on Sept. 1 in Scranton, PA by Federal District Judge Robert Mariani that the state’s Department of Corrections “protocol” for treatment — actually for non-treatment — of inmates with deadly Hepatitis C cases, violates the US Constitution’s Eighth Amendment against cruel and unusual punishment, if upheld on appeal at the Appellate Court level, could open the door for thousands of the state’s inmates with Hep-C to receive the latest highly effective but extremely costly medicines that could eradicate the virus from their bodies. It could also serve as a powerful precedent to win such treatment for the tens of thousands of infected inmates in the sprawling web of other local, state and federal prisons across the entire US who are currently being denied care for what has been called a prison epidemic of Hepatitis C.

Abu-Jamal’s loss, on a minor and correctable technicality, means that his own raging Hep-C infection, first discovered over a year ago, will continue to go untreated with those medications, meaning his liver will continue to suffer further irreversible damage from the disease — damage that could, if allowed to continue untreated, amount to an extrajudicial execution despite his having already had his original death sentence overturned as unconstitutional.

Bret Grote, legal director of the Abolitionist Law Center, an anti-death penalty organization, filed the lawsuit on Abu-Jamal’s behalf in August 2015 seeking a preliminary injunction to force the DOC to provide life-saving new anti-viral drugs to him to treat and cure the Hep-C wracking his body. He says that the reason the judge gave for denying that request was that the suit had not properly named the individuals in the Department of Corrections responsible for determining whether a prisoner would or would not receive treatment.

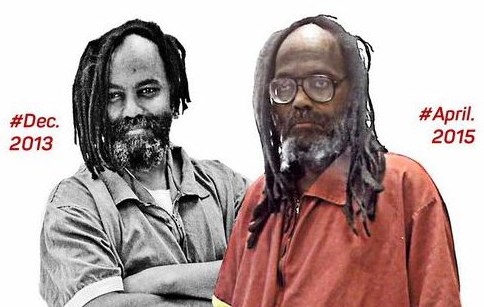

Mumia in 2013 and in 2015, showing the ravages of the Hep-C infection he contracted in the interim

Mumia in 2013 and in 2015, showing the ravages of the Hep-C infection he contracted in the interim

Grote said that the judge did say who the parties are that would have to be included in an amended filing of the suit, and that if those names are added, he could rule on the request for an injunction requiring treatment. “We had the health care director for the DIC and the former head too,” says Grote. “Our position was that they were and are responsible for implementing any treatment guidelines. But the Judge said that we should have included the members of the prison system’s Hepatitis C Treatment Committee.” He adds, “We will be getting the new papers filed as expeditiously as possible.” Grote says one motion was already filed weeks ago adding one member of the treatment committee, Dr. Paul Noel, the DOC’s chief of clinical services. A decision on that amendment to the injunction filing is pending.

Grote expressed optimism that once the treatment committee members’ names are added as defendants in the case, the judge will rule favorably on Abu-Jamal’s injunction petition.

The concern is time. The wheels of justice in the federal court system can grind painfully slowly, and if the state is able to win a new hearing on the issue, it could be months before any decision by the court. Abu-Jamal’s attorneys are resisting any new hearing, since the facts of the case were already established at a hearing last winter, when DOC witnesses admitted in court that their existing “protocol for treatment” was so strict that in reality no state inmates had been approved to receive newly invented Hep-C drugs that have demonstrated a 90-95% cure rate.

The state, like jurisdictions all over the country — and also like most state Medicare agencies — has been trying mightily to avoid providing the new drugs like Harvoni and Sovaldi, because of the costs. These drugs can run to $80,000 or more per patient for a 12-week course of treatment. Instead Pennsylvania has been, at best, providing older medicines that have terrible side effects and that are only effective less than half the time.

But after learning of the DOC’s protocol, which states that in order to get the new medications, inmates must first show signs of advanced fibrosis scarring of the liver or of even worse evidence of cirrhosis of the liver, or what are called esophageal varises — basically enlarged veins in the wall of the esophagus which can burst and cause death from sudden internal bleeding and which are caused by hepatitis liver infections — Judge Mariani was unequivocal. Noting first that the October 2015 guidelines issued by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America, entitled “When and in Whom to Initiate HCV Therapy,” recommend treatment using the new anti-viral drugs “for all patients with chronic Hepatitis C virus infection, except those with short life expectancies that cannot be remediated by treating HCV, by transplantation, or by other directed therapy,” and that the national Centers for Disease Control “states that the standard of care in hepatitis C treatment in the United States is treatment with direct-acting antiviral agents such as Harvoni and Viekira Pak,” Judge Mariani writes:

“The Court believes there is a sufficient basis in the record to find that DOC’s current protocol may well constitute deliberate indifference in that, by its own terms, it delays treatment until an inmate’s liver is sufficiently cirrhotic that a gastroenterologist determines, at the end of a lengthy, multi-step evaluation procedure taking place over a long period of time, that that inmate has esophageal varices. In the words of Dr. Noel, DOC’s Chief of Clinical Services, the presence of these esophageal varices signifies that inmates have ‘pass[ed] … into advanced disease, and … are at risk for the varices rupturing and having a severe and critical bleed, because their platelet counts are low, so they don’t clot very well, and you could have a catastrophe.” (Findings of Fact, supra, 11 52; Noel Test., Dec. 23, 2015, at 112:10-23). In the Court’s view, the effect of the protocol is to delay administration of DAA medications until the inmate faces the imminent prospect of ‘catastrophic’ rupture and bleeding out of the esophageal vessels. Additionally, by denying treatment until inmates have ‘advanced disease’ … the interim protocol prolongs the suffering of those who have been diagnosed with chronic Hepatitis C and allows the progression of the disease to accelerate so that it presents a greater threat of cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and death of the inmate with such disease. The protocol put forth by the Hepatitis C Treatment Review Committee exposes inmates in the care of DOC to these risks, despite knowing that the standard of care is to treat patients with chronic Hepatitis C with OM medications such as Harvoni or Sovaldi, regardless of the stage of disease.”

“Delilberate indifference” to the health of prison inmates would be an example of the “cruel and unusual punishment” prohibited by the 8th Amendment of the US Constitution.

Unfortunately, Judge Mariani also ruled that the named plaintiffs in Abu-Jamal’s lawsuit — including John Kerestes, superintendent of SCI-Mahanoy, the prison where Abu-Jamal is incarcerated, and two senior prison officials, Christopher Oppman and John Steinert — were for various reasons not the individuals who were responsible for deciding on granting or withholding Hep-C treatment. But he did make it clear that if the case added the members of the Hepatitis C Treatment panel, he would be ready to issue a ruling based on his findings concerning the current policy on non-treatment of the disease.

The irony is that the only reason Judge Mariani or anyone else knows today that there exists in the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections a formal protocol for non-treatment of inmates with Hepatitis-C is that it was mentioned tangentially by an attorney for the Department of Corrections during a motion at last December’s hearing. When Abu-Jamal’s attorneys, on learning of its existence, immediately moved to have the document produced, the DOC attorney attempted to have the judge examine it in private and not to release it to Abu-Jamal or the public. The judge rejected that effort and demanded that the protocol document be immediately entered into the record.

There is a long history, in the course of the 35-year Abu-Jamal court case, of judges at all levels applying special measures and rulings that have hurt Abu-Jamal, from trial judge Albert Sabo refusing to delay his trial so that a critical police officer witness said to be “on vacation” could be brought back to answer questions about his spurious claim to have heard a “shouted out” confession, to an appeal of his conviction being considered by a state Supreme Court panel on which one judge, who had previously been the Philadelphia district attorney overseeing the opposition to Abu-Jamal’s appeals refused to recuse himself. This latest decision recognizing a constitutional violation but delaying taking any action on a remedy, at least temporarily, based upon a technicality, will be viewed by some as yet another obstacle to justice being thrown at Abu-Jamal. Hopefully, however, in this case Judge Mariani is only trying to make sure that Abu-Jamal’s case is solid enough so as not to be rejected or, should he ultimately rule in Abu-Jamal’s favor and order the provision of life-saving Hep-C medication, or overturned by a higher court.

DAVE LINDORFF is the author of Killing Time: An Investigation into the Death Penalty Case of Mumia Abu-Jamal (Common Courage Press, 2003)