Any religion that professes to be concerned about the souls of men and is not concerned about … the economic conditions that strangle them and the social conditions that cripple them is a spiritually moribund religion awaiting burial.

– Martin Luther King

In their [evangelical Christians’] view, Christ did not live a perfect life so that we could follow in his footsteps, but precisely so we wouldn’t have to.

– Adam Kotsko

Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth.

– Matthew 5:5

While the left continues its favorite habit of eating itself over identity politics rivalries, Cold War journalists like Chris Matthews are losing their marbles over Bernie Sanders as a socialist. First, Matthews was going off about being shot in Central Park following a Castro take-over of America, then he lost it and compared Sander’s win in Iowa and New Hampshire to Hitler taking over in Germany. Matthews’ owners at MSNBC yanked his leash and made him apologize live for the Hitler analogy.

Then, in the South Carolina debate when Sanders had the temerity to say something good about the literacy and health programs in Castro’s Cuba (things reported on 60 Minutes), the moderates all jumped him and began beating him as if they were an LAPD cop-pack working over Rodney King. When Bernie tried to mention Saudi Arabia and other American gangster/thug allies, the beating just got more intense and more self-righteous. At this point, I think I began to holler at my TV to help Bernie out.

Cold War reaction is surfacing with a vengeance over Sander’s success, which has been explained very reasonably by Robert Reich, secretary of labor under Bill Clinton. “Today’s main divide isn’t left versus right. It’s establishment versus anti-establishment.” What does this mean for the election? “[T]he socialist label doesn’t come with the stigma it once did.”

Matthews’ reaction is mired in the past. Instead of the frantic hyperbole, there are a host of more apt comparisons in American reform history that contained elements of socialism, such as FDR’s New Deal or even the Eisenhower 1950s when strains of American socialism (of course, it wasn’t called that) seemed appropriate to educate its returning veterans, to provide them housing and to do things like create a cross-country interstate highway system — all supported by healthy public-oriented taxes.

None of the moderate Democrats — let alone Trump Republicans — seem able to even conceive of a nation with a “mixed economy” that balances all sorts of -isms for the good of the entire population, not just millionaires and billionaires. When it’s mentioned that Bernie Sanders is a democratic socialist, these moderates go ballistic and compare him to popular historic demons; what’s wrong with very mainstream American politicians like FDR for comparison? If you’re looking for edge, there’s also more radical, home-grown versions like Eugene Debs; there’s even the great American poets of bottom-up sympathy for the poor and working people like Walt Whitman or Woody Guthrie.

No, they bring up Stalin or Trump’s beloved Kim Jong-un or their favorite, Fidel Castro.

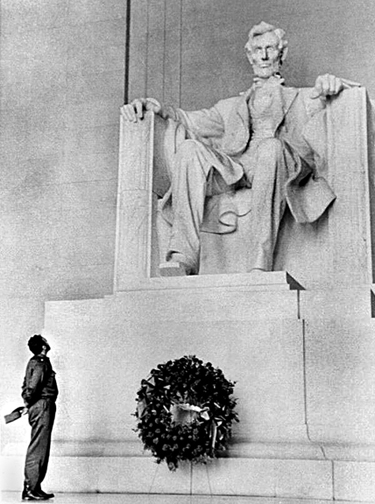

[ Fidel Castro at the Lincoln Memorial ]

As I watched them in South Carolina beat up on Sanders, all I could think of was my experiences with Latin American “socialism” in the 1980s after being raised in the south Florida of the 1950s and 1960s 90 miles from Cuba. During the missile crisis, I remember a truck-borne missile unit parked in a tomato field near my house, and sometimes we could hear the B52s warming up at Homestead Air Force Base. Some 60 years later, at the movies I recall Movietone News film that showed a portly man in a rumpled tropical white suit against a wall, then a fusillade of gunfire — and the man totally collapsing. The image was seared into my 11-year-old brain.

History is serious, but the garbage being thrown around in the debate seemed hysterical, so yesterday, that I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry or get my firearms in order.

It seems the only accurate way to look at the United States of America is as a huge, complex amalgam of interests and -isms to the point it’s impossible to see it as absolutely anything. Of course, with a narcissist as president, the -ism we most have to deal with these days is the reductionism of complexity to whatever President Sparky wants at any particular moment. This is why the teaching of Critical Thinking from first grade to twelfth grade is so vital for the nation’s future.

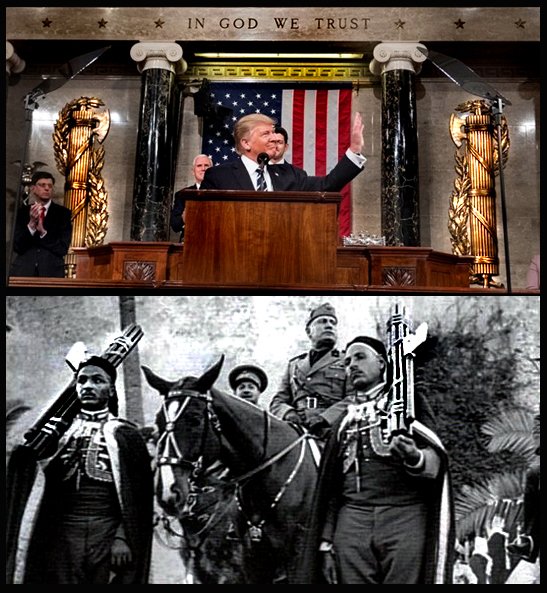

My suggestion to the Sanders campaign is if people insist on assaulting Bernie for being a democratic socialist, then fairness and decency requires that the current resident of the White House be labeled a democratic fascist and that Hitler and Mussolini analogies be released from the informal embargo that have been put on them. Personally, I’m of the school Hitler is a unique case and Hitler analogies should be avoided. But Mussolini is another story. Look at photos of Benito and his jut-jawed narcissistic arrogance and, then, look at photos of Donald Trump.

It’s my considered opinion that the reason fascist analogies are understood as out of bounds is that they contain a certain element of truth when one considers US history and especially Cold War foreign policy — and that the truth they involve may hit close to home.

[ Donald Trump and the fasces in the US House and Mussolini with two versions employed as a Roman magistrate would employ them ]

Take for example the two well-wrought bronze fasces that straddle the flag of the United States behind the speaker’s podium of the US House of Representatives. I marvel at two impressive fasces every time I watch a State of the Union speech. Can you imagine two hammers-and-sickles in that honored place? The fasces — a battle-axe surrounded by sticks used by Roman magistrates as a symbol of their power — was the symbol Benito Mussolini chose to symbolize the movement he created in the 1920s; he named that movement the fascist movement after the fasces.

I’m not saying the US has a fascist government. That would be too simple, and my point is this stuff is complicated. Those fasces don’t seem out of line to official America because, in the great complex stew of -isms, top-down America leans more toward fascism than it does toward socialism, more towards capitalism than it does toward socialism. It would be preposterous to imagine two hammers-and-sickles straddling the Stars and Stripes in the House of Representatives because hammers and sickles are tools of labor and workers. Every nationalistic and imperialistic American instinct mitigates against symbolism sympathetic to the idea of workers and socialism. We don’t call the Post Office, our Military system, the Space Program, Medicare for the aged and other social/bureaucratic features socialistic because, with all the historic propagandizing against socialism, that would freak people out. But all those institutions have socialistic qualities. We accept those beautiful fasces in the House chambers because they symbolize — the reason Mussolini liked them — brute strength and powerful leadership, the thing that often trumps democracy and makes the trains run on time.

So might there be a cultural bridge of some sort that can help ordinary, good-hearted Americans past this crazy, obsessive panic over socialism as something that’s gonna corral us all into boxcars and ship us to the gulags? In a recent New York Times op-ed, the eloquent American historian Jon Meachem has, in my mind, hit on a most interesting analogous figure for this struggle.

Jesus.

I’m an atheist, so Jesus may seem an odd idea for me to resonate with as a bridge to sanity. As an atheist, I don’t believe in a white-haired supreme being somewhere who knows everything I’m thinking, or even cares. I was raised on this by a father who taught physiology in a medical school and by a mother who was the daughter of a chemist who invented the killing ingredient in Raid insecticide. (The family joke was that Mom was studying for a PhD in biology and Dad offered her a Mrs.)

What I believe in is The Great Mystery. I don’t think anyone knows what it’s really ultimately about, even those with “faith.” Meacham writes, “I’m a Christian (a very poor one, but there we are), but I’m also a historian, and contemplating the beginnings of the story of my ancestral faith has led me to think about the uses of Jesus down the eons.” He quotes Homer: “All men have need of the gods.” Homer’s deities were many versus our culture’s single supreme being with a capital “G”. The Homer quote means to me that even an atheist — maybe especially an atheist — longs for an answer to the ultimate questions. And that human longing that’s shared by all humans, rich and poor, can be a serious social glue.

If someone has faith in their mind and heart of the existence of a Supreme Being, how different is that from someone who longs for the same idea? Faith is not certainty. Where do signs and visions come from? Outside or inside? It seems to me, whether these things are generated inside or come from outside the thinking mind and the poetic heart, the spiritual longing is no less or more real.

In the end, what churches and institutions do with the accumulated spiritual power of their congregants can be employed for good earthly ends — or not so good ends, something Meacham recognizes when he says, “Christianity has been an instrument of repression, but in the living memory of Americans it has also been deployed as a means of liberation and progress — which feeds the hope that it can become a force for good once more.” Of course, all this applies to all religions all over the world.

I first met Jesus as a kid in an affluent suburb outside New York City. My father worked for a pharmaceutical company as a researcher and, from my understanding, he wanted to move into the corporate offices. He wanted to be respected in the community. I was sent to a Sunday School in the basement of a Presbyterian church, where I met Jesus in stories and pictures; I remember him in simple terms as a poor man in a robe and sandals who was kind and helped people in need. But then something went wrong and the family moved to a small concrete-block house in rural, redneck south Dade County, Florida, which was effectively Mars to me. We were surrounded by forests of pine and palmetto, tomato fields, lime and avocado groves. At 18, I joined the army and was sent to Vietnam. I came home and went to college. Years later, as an adult, during the Reagan Wars I traveled to Central America as a photographer in El Salvador and Nicaragua. These were hot, cruel wars driven by Cold War politics.

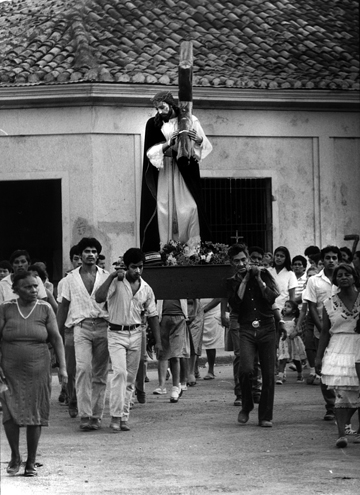

Was Jesus a socialist? (John Grant photo, El Salvador)

In El Salvador, I encountered the very same Jesus I’d encountered as a kid briefly in Sunday School. This was a time in El Salvador when the conservative Catholic church chose a bookish priest named Oscar Romero to be archbishop, thinking he was “safe” and would look the other way like all the others did. But underneath all that boring bookishness, Romero was a brave man. He was able to hear the suffering of his flock; he began to sympathize with the poor and to subscribed to the liberation theology doctrine known as “the preferential option for the poor” — instead of the usual preference for the rich and powerful. For this, he was shot in the heart one afternoon in a small chapel while giving a service. It was a time when bodies appeared in the streets every morning and people searched for missing relatives in body dumps. I’ll never forget a tearful woman telling of finding her daughter’s body — partially skinned.

The woman who found her daughter’s body in a dump partially skinned and Jesuit Priest Ignacio Ellacuria, one of six priests murdered along with two women who worked for them in their quarters at the University of Central America in San Salvador in November 1989 by Salvadoran soldiers trained and armed by the United States. Professor Ellacuria was a liberation theologist and a sociologist. (John Grant photos)

All during these years, the Reagan administration pumped money into the war and certified — wink! wink! — every six months that progress in human rights was being made by the Salvadoran government. In that very bleak time, it was the liberation theology Jesus (and the FMLN guerillas) who gave the brutally oppressed poor hope and courage; ordinary peasants studied Christ’s liberating message and became delegates of the word, traveling around preaching hope. This is the Jesus Meacham writes about as “deployed as a means of liberation and progress.” The long, bloody war was brought to an end when Salvadorans of all classes became weary of the killing. The FMLN became a political party and elected two presidents. Archbishop Romero became a Roman Catholic saint.

Meacham brings in Martin Luther King and John Lewis and the Civil Rights movement. He tells of Congressman Lewis, who was beaten near to death at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, growing up poor and how he “overcame a childhood stutter by preaching to the chickens on his parent’s tenant farm.” The boy heard King preach on the radio and was motivated toward action. He quotes Lewis: “This was love in action, what we came to call our workshop’s soul force.” In many places, Jesus has been a very real and active political force in the lives of oppressed people. The New Testament could become a guide to political action: “Blessed are they who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.”

Some argue that Jesus was a revolutionary, maybe even a socialist in the sense of working from the bottom up — all rooted in a theology of liberation meant to empower ordinary people struggling against powerful oppression.

But the theology is as polarized as America itself. And in many people’s minds, Jesus works on the side of the oppressors. These people condemn liberation theologists and call them communists. Many people were killed for this reason in El Salvador and elsewhere.

In the Fall 2019 issue of the literary journal N+1, Adam Kotsko wrote an essay titled “The Evangelical Mind.” Kotsko was raised in a rigid evangelical family and, following a personal crisis of belief and a PhD, has been writing books on religious and political topics with titles like The Politics of Redemption: The Social Logic of Salvation and Why We Love Sociopaths: A Guide to Late Capitalist Television. He was recently the subject of right-wing trolling and attacks that he has responded to with sly humor. The on-line harassment is due to a joking response he made to a question from a right-wing provocateur on white guilt that suggested maybe all white people should commit mass suicide. He seems to take this stuff in stride with a smile.

He says when it comes to evangelicalism, he’s not a scholar but a primary source. “I am not just an observer of the evangelical mind, but an example of it.” In my reading, his N+1 essay exposes what one might call the moral escape hatch at the core of evangelical Christianity. “Evangelicalism is, in many ways, the most successful social movement of our generation, but its achievement has been to shut down the possibility of the political changes we most need.” What he describes seems the antithesis of the liberating qualities of Christianity that Meacham speaks of — as in Evangelicalism vs. Liberation Theology.

“Our profoundly unjust and self-destructive society won’t be changed by using the playbook of those who believe Jesus died on the cross so they could be good suburban consumers,” he writes. “We can only seek to defeat them.”

How Christian evangelicalism really works, in Kotsko’s view, is quite interesting to think about, and it helped me understand how a cruel, amoral gangster like Donald Trump can be so revered as a leader among Christian evangelicals. The current cycle of right-wing evangelicalism began, he says, as a reaction to the counterculture of the 1960s.

“The sole political task of the evangelical community is to reproduce itself. They have no quarrel with economic inequality, with racial and gender hierarchy, with nationalism and torture and war, with environmental destruction.” For evangelicals, Christ is not a model for moral living or, as in El Salvador, a revolutionary spiritual figure inspiring liberation from oppression; no, he’s just there to forgive you for your sins. Make you feel better and part of the evangelical team. To “accept Christ” is to be freed from guilt. “To this day,” Kotsko tell us, “the attitude I associate most with evangelicals is a sneering contempt for moral striving.”

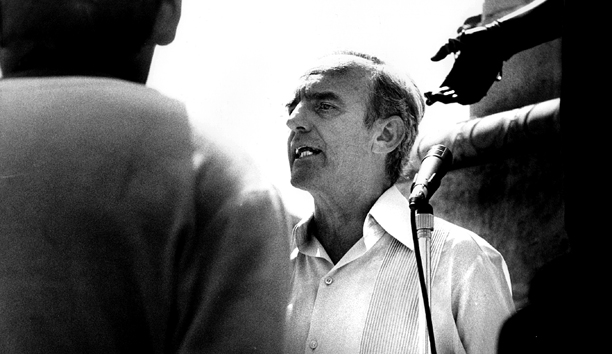

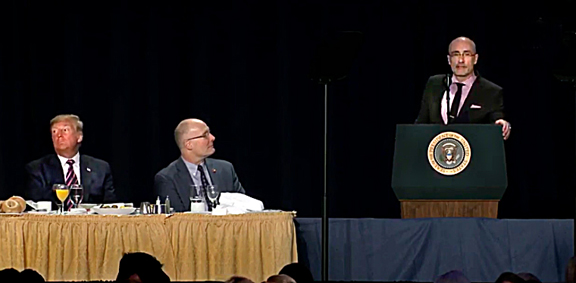

[ Arthur Brooks talks of Christian love as Donald Trump looks into space, avoiding the gaze of Nancy Pelosi a few seats away ]

Thus we have a US president revered by Christian evangelical leaders who can speak at a National Prayer Breakfast immediately following his acquittal by the Senate and, according to Meacham, “mock the New Testament injunction to love one’s enemies.” Trump did this by following Arthur Brooks, president of the American Enterprise Institute and professor of public leadership at the Harvard Kennedy School, who spoke pointedly about love for one’s enemies.

“Jesus didn’t say, ‘tolerate your enemies.’ He said, ‘love your enemies.’ Answer hatred with love. . . . This is your opportunity to show people what leadership is all about. Run toward the darkness, bring your light.”

Trump began by saying to Brooks with a smirk: “Arthur, I don’t know if I agree with you.” Then to the audience: “But I don’t know if Arthur’s going to like what I’m going to say.” Back to Brooks: “But I loved listening to you. It was really great.” Then he went on for 25 minutes about how great he is and how he was wronged by his terrible, rotten enemies, like Rep. Nancy Pelosi who sat a few seats to his right.

Meacham sums up today’s right-wing evangelical leadership this way: “It’s clear that leading conservative Christian voices are putting the Supreme Court ahead of the Sermon on the Mount.” We can clearly see how the Supreme Court has been re-shaped by Mitch McConnell and Donald Trump with the enthusiastic encouragement of Christian evangelicals.

These Christians believe the nation’s president can be morally repugnant, even evil, as long as he puts far-right judges on the Supreme Court and supports right-wing policies. These religious leaders would accept their own Devil if he could facilitate what they wanted. Jesus Christ is for them a cover for bigotry, cruelty and high-powered greed. You have to wonder: What did they do with that loving guy in a robe and sandals who got all worked up and flipped over the tables of the money-changers violating the temple?

What I learned in El Salvador and what Martin Luther King preached is that the Jesus that stands for decent, struggling, working-people isn’t afraid of these evangelicals. The liberating Jesus would encourage Chris Matthews not to be so afraid, and to look to the future instead of the past. This Jesus is all about the inheritance of the meek in Matthew 5:5.

As the bumper sticker says: THE MEEK ARE GETTING READY.