A book review of:

MY LAI: VIETNAM, 1968, AND THE DESCENT INTO DARKNESS

By Howard Jones

Oxford: 2017

(This review first appeared in The Mekong Review, published in Leichhardt, Australia)

[Click here to go to Part Two]

Monsters exist, but they are too few in number to be truly dangerous. More dangerous are the common men, the functionaries ready to believe and to act without asking questions.

– Primo Levi

On 17 March 1968, the New York Times ran a brief front-page lead titled “G.I.’s, in Pincer Move, Kill 128 in a Daylong Battle”; the action took place the previous day, roughly thirteen kilometres from Quang Ngai City, a provincial capital in the northern coastal quadrant of South Vietnam. Heavy artillery and helicopter gunships had been “called in to pound the North Vietnamese soldiers”. By three in the afternoon, the battle had ceased, and “the remaining North Vietnamese had slipped out and fled”. The US side lost only two killed and several wounded. The article, datelined Saigon, had no byline. Its source was an American military command’s communiqué, a virtual press release hurried into print and unfiltered by additional digging.

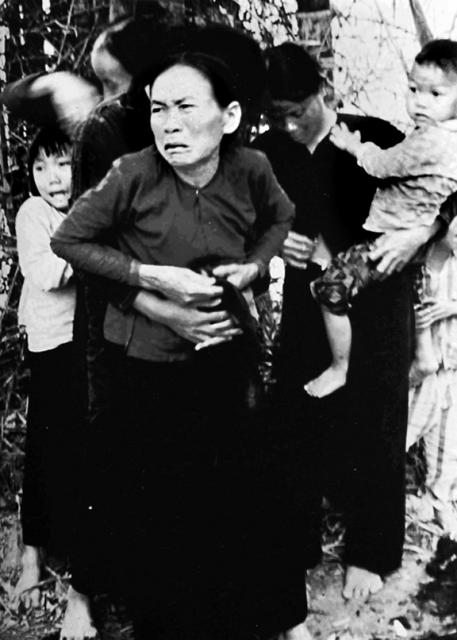

My Lai residents moments before being shot (Ron Haberle/WikiCommons)

My Lai residents moments before being shot (Ron Haberle/WikiCommons)

Several days later, a more superficially factual telling of this seemingly crushing blow to the enemy was featured in Southern Cross, the weekly newsletter of the 23rd Infantry (or Americal) Division, in whose “area of operation” the “daylong battle” had been fought. It was described by Army reporter Jay Roberts, who had been there, as “an attack on a Vietcong stronghold”, not an encounter with North Vietnamese regulars, as the Times had misconstrued it. However, Roberts’s article tallied the same high number of enemy dead. When leaned on by Lieutenant Colonel Frank Barker, who commanded the operation, to downplay the lopsided outcome, Roberts complied, noting blandly that “the assault went off like clockwork”. But certain after-action particulars could not be fudged. Roberts was obliged to report that the GIs recovered only “three [enemy] weapons”, a paradox that warranted clarification. None was given. It was to be assumed either that the enemy was poorly armed or that he had removed the weapons of his fallen comrades — leaving their bodies to be counted — when he retired from the field. Neither of the news outlets cited here, nor Stars and Stripes, the semi-official newspaper of the US armed forces, which ran with Roberts’s account, makes reference to any civilian casualties.

It would be nearly eighteen months later when, on 6 September 1969, a front-page article in the Ledger-Enquirer in Columbus, Georgia, reported that the military prosecutor at nearby Fort Benning — home of the US Army Infantry — was investigating charges against a junior officer, Lieutenant William L. Calley, of “multiple murders” of civilians during “an operation at a place called Pinkville”, GI patois for the colour denoting human-made features on their topographical maps of a string of coastal hamlets near Quang Ngai.

With the story now leaked, if only in the regional papers — it would migrate as well to a daily in Montgomery, Alabama — the Fort Benning public information officer moved to “keep the Calley story low-profile” and “released a brief statement that the New York Times ran deep inside its September 7, 1969 issue”, limited to three terse paragraphs on a page cluttered with retail advertising. The press announcement from the Army flack had referred only to “the deaths of more than one civilian”. In the nation’s newspaper of record, which also mentioned Calley by name, this delicate ambiguity was multiplied to “an unspecified number of civilians”. Yet, once again, the Times had been enlisted to serve the agenda of a military publicist and failed to approach the story independently.

.jpg)