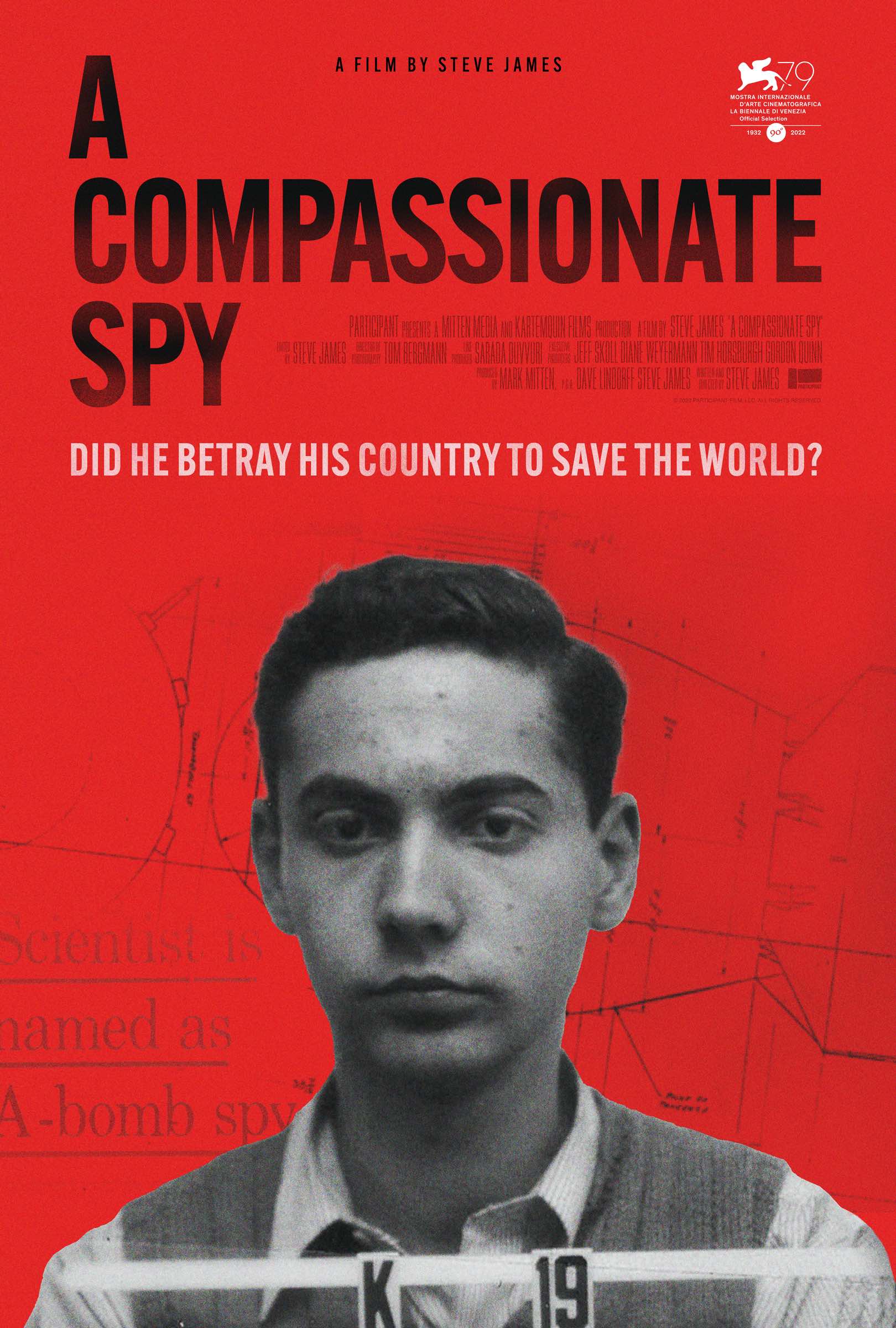

New Documentary Reveals How A Teenage Army Physicist Named Ted Hall Saved The Russian People From A Treacherous U.S. Sneak Attack In 1950-51—And May Well Have Prevented A Global Nuclear Holocaust

The provocative documentary “A Compassionate Spy” tells the amazing but almost unknown story of a “near-genius” Harvard physics major, who at age 17, was selected to help develop an atom bomb before the Nazis did.

At 18, after graduating from Harvard, Ted was the youngest physicist to work on the atomic bombs at Los Alamos, New Mexico. He worked with uranium and the implosion system for the plutonium bomb used in the Trinity test on July 16, 1945, one month before that bomb type killed tens of thousands of civilians at Nagasaki.

Between the bombings at Hiroshima, August 6, and Nagasaki, August 9, somewhere around 200,000 civilians were killed, and a similar number died within some months afterwards from radiation sickness and injuries.

The film also illustrates why and how Ted shared his knowledge with the Soviets: to prevent a post-war U.S. perhaps heading toward fascism and/or world domination intoxicated by having a nuclear monopoly. He foresaw correctly because, by 1946, Wall Street bankers and weapons industrialists had convinced President Harry Truman, as the film shows, to produce 400 more atomic bombs to attack the Soviet Union in 1950-51, kill millions of its people, and take over its huge land and natural resources.

Nine months after beginning work on the bomb, in October 1944, Ted received leave to celebrate his 19th birthday in New York City. It was there that he made his first contact with a Russian, Sergei Kurnakov, who was a writer and an undercover intelligence officer. Ted gave detailed plans for the plutonium bomb to the Russians, sometimes using his enthusiastic friend Saville Sax, whom he roomed with at Harvard, as courier.

In transmitting communications, the two novice spies used Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Ted’s Soviet spy code name was MLAD (youth).

Ted’s information corroborated what the Russians were receiving independently from scientist Klaus Fuchs. So critical was this to Soviet scientists’ ability to develop an atom bomb of their own that they made a virtual copy of the Nagasaki bomb, which was Ted’s specialty.

They exploded a test bomb on August 29, 1949, between two and five years earlier than otherwise expected by U.S. experts. According to the film, Truman was then forced to cancel his plans to pre-emptively invade Russia because retaliation by the Soviets would be likely.

(A similar dilemma was faced by President John F. Kennedy during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis when Wall Street capitalists, the Pentagon and the CIA, which was created under Truman in 1947, saw a chance to annihilate Soviet peoples in several areas. The U.S. had sought to destroy the Soviet Union ever since the Wilson administration invaded Russia following the 1918 Bolsehvik revolution. When Kennedy chose another path, a naval blockade of Cuba, it worked. The missiles were withdrawn. Yet Kennedy had also signed his death warrant).

This documentary, however, is not a political film per se. Central is the passionate, durable love story of Ted and his wife Joan, intermeshed with the history of the atomic bomb-making, its use and near-use.

Journalist and producer Dave Lindorff initiated the film idea in 2018. He, together with director Steve James and fellow producer Mark Mitten, started with three days of interviews with Joan, now 93. Joan also gave the team a video cassette which Ted, at his attorney’s suggestion, made for the “historical record.” Ted explains his reasoning for volunteering as a Soviet asset at Los Alamos.

Lindorff received the I.F. Stone “Izzy Award” for “Outstanding Independent Journalism” over his five-decade career and specifically for his exposé: “Exclusive: The Pentagon’s Massive Accounting Fraud Exposed,” The Nation, December 2018.

Steve James, two-time Academy Award nominee, was called “Chicago’s documentary poet laureate,” by The Hollywood Reporter in its September 2 review of the first film showing, which took place at the Venice Film Festival. One thousand viewers filling the Lido Hall rose to applaud for five minutes at its conclusion. A day later, the U.S. premiere was held in four full theaters at Colorado’s Telluride Film Festival.

So far, the film has been presented at six U.S. and European film festivals with at least two more to come. The funding comes from Participant Media, which is receiving bids for general distribution.

This reviewer, and my companion-photographer Jette Salling, saw the film in Cambridge where Joan and Ted lived from 1962 until his death in 1999. She still lives in the same house.

Although I am not a professional film reviewer, my six decades of peace and racial equality activism, and five decades of professional journalism lead me to the conclusion that A Compassionate Spy is both a horrendous and great film.

Horrendous because the United States of America, claiming to be the greatest democracy in the world, killed hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians in the Pacific War gratuitously.

Horrendous, all the more, because the U.S. elite and their politicians callously targeted millions more to die in the Soviet Union just as World War II was won, primarily by the USSR.

Greatest because of what two men, Ted, and Klaus Fuchs (see below) did to prevent the genocidal action. Ted Hall, and a handful of other scientists and couriers, deserve world-wide recognition by all humans who have any sense of brotherhood, sisterhood, solidarity and world peace.

One of the last public statements Ted Hall made just before he died was to encourage the next generations to demand government policies that do not put the world at such risk again.

[Go to Covert Action Magazine link for rest of article:] Can An American Scientist Who Smuggled Critical Nuclear Secrets to the Russians After World War II Be Considered a “Good Guy”? New Film Says Yes. | CovertAction Magazine