London and Philadelphia — Over three thousands miles and more than forty years in age separate anti-violence activists Bilal Qayyum and Noel Williams, yet each advocates a similar solution to ‘the problem’ they seek to solve in their respective cities located on separate sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

Qayyum, 69, of Philadelphia, Pa and Williams, 25, of London, UK each see employment as the critical tool needed to counter violence among youth and young adults living in low-income communities.

“In all my years of working to reduce violence, it’s very clear to me that jobs are a major solution to reducing violence in low-income communities,” Qayyum said, speaking about his roots in violence-reduction efforts dating back to the 1970s when he was an anti-gang worker.

“Jobs, well-paying ones, give people a strong feeling of worth. Poverty breeds violence.”

Sadly, Williams and Qayyum each see the same roadblock on violence reduction: the persistent failure of public sector authorities on both sides of the Atlantic to fully engage community-based persons with the front-line experiences required to effectively resolve the “violence problem” that authorities proclaim they want to solve.

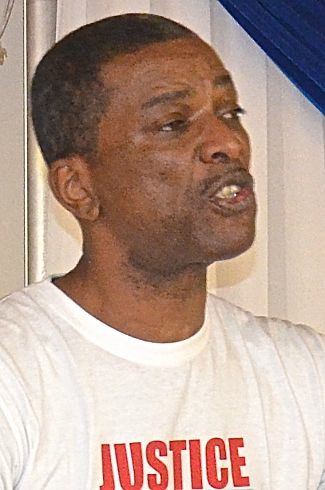

Noel Williams (all photos by Linn Washington, jr.)

Noel Williams (all photos by Linn Washington, jr.)

Williams, an ex-gang leader in southwest London turned university student, said, “Who comes to me and asks for advice? I know gangs. I know how it feels to be shot and how it feels to walk down the road feeling oppression from police.”

Williams bristles at the fact that authorities continually employ persons with no life-connection to violence as paid staff to lead violence-reduction initiatives.

“If you want to help people who’ve been to prison, why is it that people who’ve been in prison are never hired?” ex-inmate Williams asked.

“Yes, you need academics and people with college degrees, but you also need people who understand,” he explained.

Williams, who works with youth while attending a university outside of London, said, “Authorities are polite at meetings but they just don’t listen to us when it comes to the policies and programs they do.”

Both Williams and Qayyum said greater private-sector involvement is essential to reverse the crisis in unemployment among youth and young adults.

“Corporations have to buy into solving the jobs problem,” Qayyum said.

Connections between London and Philadelphia extend beyond William Penn, the London native who founded the American city in 1682.

Philadelphia has the highest level of poverty among America’s ten largest cities. The city’s poverty rate of 26.9 percent is statistically the same as in London, where 27 percent of the residents of that rapidly gentrifying city live in poverty.

In London, unemployment among 16-24 year olds is 2.5 times higher than among persons aged 25-64, according to the “London Poverty Profile” released in October 2015. In Philadelphia unemployment among 16-24 years olds is slightly less than twice that of persons aged 25-64.

Investigators often cite youth unemployment as a major factor underlying the August 2011 riots that rocked London and nearly a dozen other cities around England. That outburst followed the fatal police shooting of a young black man in the impoverished Tottenham section of North London.

The 2012 report from North London Citizens, an alliance of 40 civic institutions in the Tottenham area, found that 53.1 percent of the 700 people interviewed listed unemployment as the “key cause” of rioting in Tottenham. Another “major cause” of the rioting was poverty, according to 32.9 percent of those respondents.

Government building torched during 2011 riot -Many viewed 2011 as a rebellion against oppressive government policies

Government building torched during 2011 riot -Many viewed 2011 as a rebellion against oppressive government policies

An investigation into the 2011 riots by London’s Guardian newspaper in collaboration with the Social Policy Department of the London School of Economics found that 79 percent of the riot participants listed unemployment as a riot cause and 86 percent listed poverty as a cause.

While top officials of Britain’s national government and much of British media cited greed as the main motivation of rioters (many of whom engaged in looting) riot participants interviewed during the Guardian/LSE investigation listed greed below seven other factors that included policing, government policy and the fatal shooting of Mark Duggan, along with poverty and unemployment.

An inquiry into the 2011 riots commissioned by the British government also listed unemployment and poverty as underlying issues. But the government’s written response to its own inquiry declared: “It is not acceptable that poverty, race and the challenging economy were used as excuses for the appalling behavior we saw on our streets in August 2011.”

Dr. Jacob Whittingham, who operates a youth program in London that emphasizes education and entrepreneurship, said Britain’s national government, after the 2011 riots, seemingly focused on stiff imprisonment for rioters and budget cuts, including funding reductions for youth programs.

“Basically people give lip service. There was no attempt by the central government to understand why the riots happened,” Whittingham said. “There was no urgency to do something because people don’t listen.”

In 1985, an earlier riot seared Tottenham after the death of a woman during a police raid. The governmental inquiry into that earlier riot criticized unemployment and poverty in Tottenham along with abusive policing -– the same elements that drove the 2011 outburst that spread across England.

According to the 1986 report of the “Broadwater Farm Inquiry,” unemployment for “young Black men was a terrible 83%.” Over 90% of Tottenham adults interviewed during that inquiry saw “unemployment as a big problem.”

Veteran Tottenham rights activist Stafford Scott said the recalcitrance in Britain to earnestly addressing unemployment and poverty among non-whites is rooted in racism. That Broadwater report from three decades ago cites testimony Scott gave to the inquiry.

Stafford Scott

Stafford Scott

“White Britain does not accept racism in real time,” Scott said during a recent interview, “now there is an admission that racism existed in the 1980s. But back then when we raised the issue of racism, they told us to F – – k off.”

While Noel Williams and Bilal Qayyum have never met one another, they have had experiences with the hometown of the other.

Williams visited Philadelphia in 2012, when he spent time in North Philadelphia, an impoverished area riddled with crime that is similar in some ways to his London community of Wandsworth.

“One big similarity I saw was we are all broke. We have no money,” Williams said. “In North Philadelphia there were no places for youth to socialize…there were few [recreation centers]. They are shutting down the [recreation centers] here due to government austerity and that puts young people out on the streets where they don’t need to be.”

Qayyum has never traveled to London but he vividly remembers a meeting with a group of young people from London years ago. Some in that interracial group that Qayyum met with had participated in gang activities.

“They all talked about the lack of opportunities and getting work,” Qayyum said. “They talked about dropping out of school and living in neighborhoods with high numbers of folks using drugs. Sounded like Philly.”

London activist Temi Mwale, 20, became engaged in anti-violence activities after the murder of a close friend five years ago.

“There is no chance to solve violence without ending the ‘state violence’ of poverty, hopelessness and police brutality,” Mwale said, criticizing government officials at local and national levels for failing to see the sources that create violence.

Temi Mwale

Temi Mwale

Government officials, Mwale said, “don’t want to hear the deep story on youth violence. All they see is gangs as the problem, not the poverty that contributes to gang activity. One of my frustrations in dealing with government officials is they ask the same questions over and over. That shows they are not listening.”

A report released in January 2016 by the Centre For Crime and Justice Studies of Manchester Metropolitan University documented the inaccuracy of claims by British police, who declare that since young blacks dominate gang membership they are demonstrably the most violent thus deserve enhanced enforcement like Britain’s version of America’s infamous “Stop-&-Frisk.”

Police and court data cited in the Centre’s report document that black youth were not those responsible for the most serious youth violence.

In London for example, police list blacks as 72 percent of that city’s gang members. But official justice system data collected for that report found that non-blacks committed 73 percent of the serious youth violence in London.

British Prime Minister David Cameron, leader of Britain’s Conservative Party, has made public pronouncements during recent months about his intent to address persistent race-based inequities.

While Cameron’s words may represent a step forward, Simon Woolley, Director of Britain’s Operation Black Vote, said the issue is holding the Prime Minister accountable when his government is meanwhile “undermining civil society,” particularly with austerity budget cuts that disproportionately impact non-whites.

Woolley remains critical of the national government’s lack of investments after the 2011 riots, for example in festering areas like unemployment among youth and young adults –- including young adults who have college degrees. That lack of investment arose from a consensus among the elite that the cause of the 2011 riots was “anti-social behavior with no connection to social and economic inequalities,” Woolley said.

Woolley warns, “There is a young underclass out there that can explode at anytime.”