“The Face of Evil,” flashed the eye catching headline in Brazil’s major daily on a morning late this March, and the accompanying photo of Army lieutenant-colonel Paulo Malhaes, retired, could not have portrayed a more convincing ogre had it been photoshopped by central casting. Malhaes, a self-described torturer and murderer operated in the early 1970′s, the most repressive period in Brazil’s harsh era of prolonged military rule.

Retired Army Lieutenant Colonel Paulo Malhaes testifying to torture in the early 1970s

Retired Army Lieutenant Colonel Paulo Malhaes testifying to torture in the early 1970s

In depositions covering many hours, first recorded by the journalists of O Globo who got the scoop, and then before the Rio de Janeiro State — and the Brazilian Federal Truth Commission — Malhaes described in dispassionate but grisly detail how bodies of dissidents who died under torture were disposed of. “There was no DNA at the time; you’ll grant me that, right? So when one was tasked with dismantling a corpse, you had to ask which are the body-parts that will help identify who the person was. Teeth and the fingers alone. We pulled the teeth and cut off the fingers. The hands, no. And that’s how we made the bodies unidentifiable.” After which, the mutilated dead were dumped at sea, having first been eviscerated to prevent them from floating to the surface.

In marking the recently passed 50th anniversary of Brazil’s April 1, 1964 military coup that deposed popularly elected President Joao Goulart, Brazilians have been offered a kaleidoscope of opportunities to revisit and discuss that troubling past, and, for some, to overlay the impact of the dictatorship years on a society restored to democracy for over a generation, but in which the deepest structural problems remain unchanged. Many axes were being ground on these topics in the rich offering of articles and opinion pieces in the daily press as the coup’s anniversary day approached. Very few, of course, sought to defend the dictatorship, which, nonetheless, appears to have been the sole motivation behind Paulo Malhaes’ sudden impulse to seek repeat performances for his macabre confessions on the public stage, an agenda cruelly underscored by his brazen refusal to express remorse or reveal the names of his commanders.

In one bizarre aside, Malhaes confided a disassociated feeling of “solidarity” for the family of Rubens Paiva, a federal deputy allied with Goulart’s party whose murder and disappearance in 1971 Malhaes himself apparently had a hand in. It was “sad,” the colonel said, that Paiva’s family had to wait 38 years to learn the specifics of his fate, already made public from other sources. Malhaes quickly insisted that his comment not be interpreted as “sentimentality.” He hadn’t questioned his mission back then, and he still didn’t. “There was no other solution. They [my superiors] provided me with a solution,” written broadly enough for Malhaes to justify his butchery.

Most Brazilians, according to a recent poll, overwhelmingly favor Brazil’s current form of representative democracy as being far superior to any other way the country was governed in its predominantly authoritarian past. Constitutionally the Brazilian military is under civilian control in an arrangement, formally at least, similar to what prevails in the U.S. And, according to published comments by the current Minister of Defense in the Workers Party government of President Dilma Rousseff, the Brazilian Armed Forces are no longer fertile ground for anti-democratic elements. It should not be viewed automatically as a provocation to wonder if the minister, a highly regarded career diplomat, Celso Amorim, may not be whistling past the graveyard.

A cartoon from Brazil on the history of the military dictatorship

A cartoon from Brazil on the history of the military dictatorship

I guess the question would be, under what circumstances could it happen again? Not that the Brazilian brass are presently chaffing to impose another lock-down if, say, the country’s increasingly vexing social and economic problem were to suddenly escalate out of control? In fact, while a strong majority of Brazilians, according to the same poll, wearily agree that their political system is broken, they are equally committed to using democratic means to fix it. The military option barely registers today in the opinion polls. And yet the Brazilian military, from an American vantage point, still appears to operate with a great deal of autonomy and maintains a rather intimidating social presence through its policia militar — the Robo Cop-outfitted riot police known for their brutality, which the Brazilian Left condemns as a relic of a militarized police state.

Some evidence of the continued existence of an organized military party surfaced in minor news stories in the run-up to the anniversary in a reminder that currents of paternalistic conservatism remain deeply etched in Brazil. How else to explain the repeated election to public office of a man like Jair Bolsonaro, a federal deputy from Rio de Janeiro State (presumably the sticks) and a member of the military reserve. Bolsonaro expressed his nostalgia for the dictatorship during a session of Brazil’s Chamber of Deputies called to officially “remember” the day of the coup by having associates unfurl a seventy-foot long banner that read, “Kudos to the military, thanks to you Brazil is not Cuba.” The center left deputies in the Chamber turned their backs and refused to recognize that the offending recidivist had been conceded the floor. Pushing and shoving ensued, and the chair of the session, decrying a regrettable breach of parliamentary etiquette, reluctantly brought the session to a close.

Now, granted, Jair Bolsonaro is a piece of work, as a quick scan of the man’s reported opinions on social and cultural issues makes obvious, not least his chronic expressions of homophobia. But he clearly has an electoral base. Moreover, his current affiliation with the Brazilian Progressive Party puts him in the company of some of the major collaborators during the dictatorship who helped sustain and direct the regime from high posts in civil society, economists like the late Roberto Campos, and the still very active Antonio Delfim Netto, who at 85 poses in the Chamber of Deputies as a Democrat. What plays with the mind of an outsider trying to navigate the chutes and ladders of Brazilian politics is the seemingly ill-placed fact that Bolsonaro’s party today also supports the government of former leftist guerrilla Dilma Rousseff.

Bolsonaro’s stunt failed to distract from the twin narratives of torture and victimhood that dominated public attention during these days of remembrance. Malhaes had grabbed the headlines temporarily, but muted accounts from testimonies of other torturers heard before the state and federal truth commissions also circulated in a slowly drawn-out process of putting faces to those still kicking who did the dirty work of the generals and the other high placed elites not in uniform. A band of youngsters engaged in what Brazilians call the social action movements have been conducting escraches – where they track down the whereabouts of a surviving torturer and subject him to public humiliation.

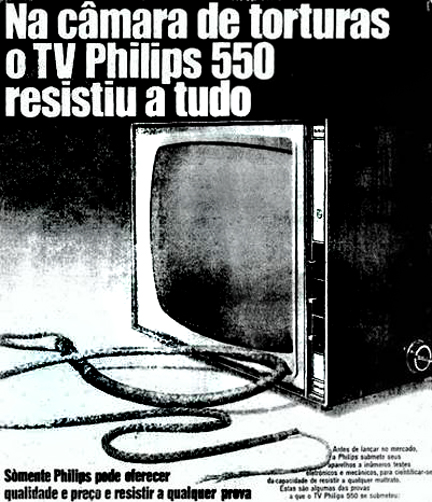

A1969 Philips TV ad: “In the torture chamber, the Phillips 550 can’t be broken.”

A1969 Philips TV ad: “In the torture chamber, the Phillips 550 can’t be broken.”

On March 31, or “revolution day” as styled by the golpistas, 150 activists of Youth Rise Up papered the residence in Brasilia of Carlos Alberto Brilhante Ustra, a known and unrepentant retired colonel who commanded an infamous torture center in Sao Paulo, with denunciations and posters of the faces of the tortured and disappeared. But it was a pamphlet produced from one corner of the Left featuring a reprinted ad placed by the Phillips Electronics Company in a Brazilian newspaper in 1969 that infuses the theme of torture with a prior psychological predisposition within the Brazilian historical memory, a predisposition linked to the country’s prolonged legacy of slavery. This state of mind is still familiar in the all but quotidian reports of contemporary police and prison practices. The print ad shows a photo of a curled bull whip next to the company’s latest model TV. The copy reads, “In the torture chamber, the Phillips 550 can’t be broken.” That, of course, did not apply to people.

“To oppose the authorities, to advocate social change or even political reform was to place yourself beyond the law.” These words used by Tony Judt to describe life in Nazi- dominated Europe during World War II echo over the world Brazilians sufferedthrough in the worst days of their dictatorship. Nothing in modern history, of course, matches what the Nazis inflicted. And in fact the Brazilian generals did not turn the screws tightly in the first few years they governed. Moreover, as it often annoyingly pointed out to Brazilians, the dead and disappeared who numbered in the tens of thousands at the hands of military regimes in Argentina and Chile, both inaugurated a decade after 1964, far outnumbered the body count in Brazil, where the total of the disappeared is given as fewer than five hundred. It’s a fact that brings solace to few Brazilians.

By 1968, the rule of law was totally suspended in Brazil, habeas corpus a receding memory, and brutality doled out in increasingly harsh doses at any sign of dissent. The heavy weight of repression and censorship in Brazil entirely suppressed the public sphere of open discussion, much less independent political action, and in this atmosphere a clandestine resistance arose which for a time made the rulers sleep less easily, especially after such dramatic actions as the kidnapping of the U.S. ambassador Charles Elbrick in September 1969. But the resistance in Brazil, albeit widespread, was never a match for the regime’s security forces, all the less so since conditions for educating and mobilizing an activist popular base to challenge the regime from below were utterly eliminated.

In the interim between the departure of the generals and full restitution of representative constitutional government, and today, much has changed in Brazil. Most dramatically there is the emergence of a genuine middle class, not so distinct one supposes from the consumers of an enlarged internal market that Joao Goulart and his allies had sought to lay the groundwork for in 1964 before the coup. And yet the stark existence of two separate societies at Brazil’s economic extremes – the obscenely rich on one end, the equally obscenely impoverished on the other – remains scandalously frozen in time.

Today the union rank-and-file and the social action movements are filled with the sons and daughters of this new middle social stratum, who, whatever other levels of education they have benefited from, are fully wired to the Internet and the social media. Given that this demographic barely existed in the time of the dictatorship, it is not surprising that the majority of the militants who fought the regime rose among the decent-minded youth of the privileged classes–young people who found Brazil’s intransigent backwardness was historically, ideologically and morally repugnant. It was to this class that most of those tortured and disappeared for political reasons during the dictatorship belonged.

Overall the militants were highly educated. When individuals from this milieu were moved to action, many banded around tightly knit cells brought into existence by the tactical limitations of the struggle, while others joined larger clandestine Marxist oriented parties that had embraced the necessity for armed resistance. Because Brazil’s social order was so skewed, no institutional space existed that would have brought the Brazilian masses into the arena of resistance. The urban elites in modern Brazil from whom the militants were drawn have known the poor most intimately in their own homes as domestics and nannies, or as porters in their apartment and office buildings, the serving class being primarily Afro-Brazilian. Otherwise, in 1964 Jim Crow Brazilian-style was the order of the day.

Did the poor feel resentment? Most assuredly they did, I am told by Patrick Hughes, an Irish missionary working in the slums of Sao Paulo from 1963 till 1972, when the generals finally expelled him from Brazil. In Hughes’ experience “the peasants (most had migrated from the countryside) totally supported the military action. Who were these rich kids that thought they could destroy the beautiful buildings they lived in for free. A bunch of Communists they were told, though few of them knew want a Communist might be.”

The militants, in that sense, were sitting ducks. They were rounded up and viciously tortured by agents bent on extracting the names and whereabouts of their comrades. Most survived the torture sessions, and were subsequently imprisoned. Cultural icons too visible to rack, like Chico Buarque or Caetano Veloso, were often, figuratively speaking, shown the instruments of torture and the cell door, then given a option of going into exile. In the case of the kidnapped American ambassador, a handful of militants were freed from prison and allowed to leave the country in exchange for his release.

It is interesting to learn in what manner those subjected to torture by the military became re-integrated into Brazilian economic and political life after 1979, when an amnesty was declared that covered the so-called terrorism of the militants as well as the crimes of the military, and allowed those in exile to return home. One of the best-known participants of an armed struggle group, Dilma Rousseff, now occupies the country’s presidency. Many others have had distinguished careers, and most have jettisoned the Marxist-oriented politics of their youth, some to follow the more convenient paths of neoliberal advancement.

And yet, however the lives and politics of the former militants may have diverged during the past thirty-five years, those who were tortured, along with the families of the disappeared, have found a bully pulpit since the establishment of the truth commissions, and in apparent unison, are instructing their fellow citizens on the various meanings they associate with their tales of individual loss and suffering. There is not a whiner among them that I could detect. Their shared agenda is strictly about justice, not vengeance, with only a tinge of moral finger-shaking. The latter finds expression in the appeals to fellow Brazilians to enshrine these ignominious deeds as a prophylactic in the national memory. This is the Nunca Mais (Never Again) moment to shame the national conscience. The political agenda is more directed.

The victims are arguing that the systematic torture of political prisoners during the dictatorship was a policy of state, and not simply the elected perversions of autonomous units operating independently or unbeknownst to the chain of command. They insist that this fact must be officially acknowledged by the government, and by the high command of the Brazilian armed forces. On a less symbolic level, a campaign to pressure Brazil’s federal legislature and sectors of its judiciary to revisit the amnesty of 1979 appears to be gaining ground among the organized sectors of pubic opinion. The demand is to remove the exemptions of impunity to criminal acts like torture, murder and the disappearance of bodies. The counter-argument that the “terrorists” also committed acts of violence, including assassinations, is typically dissolved by the legalistic rejoinder that the militants already received punishment enough. And in the court of public opinion, the majority of Brazilians seem to cast the military, not the militants, as the bad guys in this exchange.

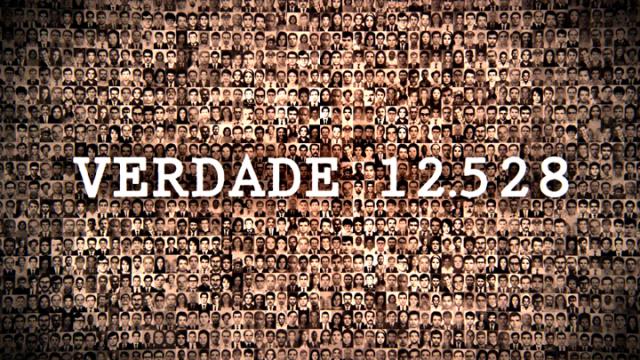

"Verdade 12:528", a documentary film critical of the Brazilian Truth Commission

"Verdade 12:528", a documentary film critical of the Brazilian Truth Commission

During my recent stay in Rio from mid-March into early April I was able to view a soon to be released documentary film called Verdade 12:528, the numbers referencing the law that brought the Brazilian Truth Commission into existence in 2013. The film is a polemic aimed primarily at that very Truth Commission, which is criticized for its timidity in confronting the crimes of the military. This is an important internal discussion today in Brazil between the activist Left and the establishment Left who currently govern the country, and is a theme I shall return to in a subsequent report.

The film is beautifully constructed, and its immediate value for me was to see and hear the accounts of the aging militants, the children of Rubens Paiva, and the widow of the equally legendary journalist Wladimir Herzog, found hanged in his cell, but not believed to have been a suicide. Added to these are the unadorned voices of several country people who once aided a base of guerrillas deep in Brazil’s interior that was totally wiped out not unlike what befell Che and his comrades in Bolivia. The film will certainly find its most important audience in Brazil, and lend impetus to the campaign to thoroughly investigate the state policies during the dictatorship, assign the correct historical judgments, reverse the amnesty law, and bring the more notorious surviving criminals, whether military or civilian, to justice.

It is unlikely, however, that such trials will ever take place. The political climate in Brazil today does not favor such an outcome. Despite the torrent of attention given to the approaching 50th anniversary of the coup by the print media, and also within the many public forums conducted by the truth commissions and in a spate of academic seminars and meetings, several of which I attended while in Rio, the president and former guerrilla Dilma Rousseff held her tongue. Only on April 1st, did Dilma finally speak. And while she was uncompromisingly clear in recognizing the historical significance of the resistance in which she had played a role, and paid homage to those who had suffered torture – as she had – or death, she insisted that her government would make no attempt to reverse the conditions of the 1979 amnesty.

This was not a task for the executive, Dilma argued, but for the legislature. There was in this pragmatic decision a recognition that the military ghost had still not been entirely laid to rest in Brazil, and that in the close re-election campaign Dilma faces this fall, it would be unwise to stir up an unsettled past. Informed public opinion is one thing. But most of the voting public is not deeply invested in this discussion, and who knows what polemic from the right to rehabilitate the military image might stir the sympathy of the electorate?

What is true for now, however, is that the public image of the Brazilian Armed Forces has never been lower since democracy was restored. Still, the brass have been permitted by their putative civilian superiors to maintain a stubborn silence, refusing for over a year to respond to the Truth Commission’s repeated requests for exact information about how the torture centers were set up and administered. In what can only be interpreted as a further gesture of defiance despite intense public pressure, the brass waited until April 2 to finally submit. Defense Minister Amorim communicated to the Truth Commission that an inquiry would be conducted internally by the armed forces focused on the seven most infamous torture chambers housed within military installations during the dictatorship. Can one doubt that their final report will reek with the language of exoneration?

Chico Caruso, editorial cartoonist for O Globo, imagined a more devilish contingency. Chico’s front page drawing on April 1st is a line up in caricature of the five generals who ruled in the dictatorship, their backs turned to the viewer. They are raising their glasses in a toast. A calendar shows the date is March 31st. “Cheers!” they exclaim. “In a little while we’ll be back.”

Michael Uhl is a Vietnam veteran who worked in intelligence; he is author of the memoir Vietnam Awakening: My Journey from Combat to the Citizens’ Commission of Inquiry on U.S. War Crimes in Vietnam. He’s currently working on a second memoir. He speaks fluent Portuguese and has written travel guides on Brazil. He lives in Maine.