A Pennsylvania State historic marker dedicated to heroes of 9/11 stands near a bend in a road that cuts through rural farm fields sixty miles west of Philadelphia, the city famous for Independence Hall and other fabled sites associated with the birth of the United States.

This marker does not honor the persons killed in the crash of Flight 93 on September 11, 2001 near Shanksville, Pa, a small community about 180-miles west of the small community where this marker stands.

However, this marker does recognize heroes who battled terrorism, albeit the persistently denied yet deadly domestic terrorism that predates America’s “War on Terror” launched in the wake of the September 2001 attacks.

This marker commemorates the Christiana Riot – a deadly clash at a farmhouse where a Maryland slave owner died during an armed skirmish with African-Americans who lived in the small Lancaster County village of Christiana.

Christiana Riot historic marker. LBW Photo

Christiana Riot historic marker. LBW Photo

The slave owner came to Christiana to reclaim his ‘property’ – three of the four black men who escaped from that slave owner two years before the clash. African-Americans blocked this attempted re-enslavement effort.

Despite the fact that freedom and the rule-of-law were central in that September 11, 1851 event recognized by that Pennsylvania State historic marker, some Americans today reject recognition of those black freedom fighters as heroes…sharing sentiment with many Americans of 1851.

Those escaped slaves sought the same freedom that white Americans – then and now – consider an unquestioned birthright.

That trio took refuge on the farm owned by William Parker, an African-American who also fled slavery in the adjacent state of Maryland. Following that deadly clash, Parker, his family and the trio of escapees fled into Canada.

Forgotten in the ruckus around notions of who should receive the full measure of America’s birthright freedom and the propriety of resistance to gross violations of the rule-of-law is this reality. The actions of William Parker and his neighbors were about both solidarity with the enslaved and self-preservation for themselves against terrorism from white racism.

In 1851 when federal law sanctioned return of escaped slaves, the federal government routinely ignored its law enforcement duty to protect free blacks from kidnap into slavery. (In fact, federal marshals accompanied the slave-owner posse that launched this attack.) The Academy Award-winning 2013 movie “12 Years a Slave” depicted the brutal ordeal endured by one of the thousands of free blacks illegally kidnapped into bondage.

William Parker had headed a self-defense group to protect his black neighbors from kidnapping by slave catchers who regularly raided Pennsylvania and other Northern states.

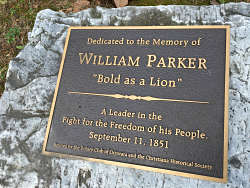

Welcomed recognition of William Parker. LBW Photo

Welcomed recognition of William Parker. LBW Photo

In December 1799 black leaders in Philadelphia sent a petition to the U.S. Congress that asked America’s national legislature for protection from Fugitive Slave Law “abuses” – the kidnap of free blacks into slavery.

Congress indignantly rejected that 1799 plea for rule-of-law protection of freedom, a stance disturbingly similar to contemporary congressional inaction on police brutality that abuses more law-abiding blacks daily than suspected law-breakers of any color.

That 1851 Christiana Riot is another link in the chain of freedom-robbing institutional racism that connects America’s colonial past with contemporary times.

Surprisingly, consideringr the racial injustices rampant in 1851, the blacks and one white arrested after the Christiana Riot who blocked the terrorist actions of predatory a southern slaver-owner and his accomplices won acquittals. That failure to convict enflamed white Southerners and Northerners alike who railed about rule-of-law failure to protect their property and/or privilege.

In 2016, as in 1851 and 1951, the persistence of race-based inequities embedded in American society gives ‘freedom’ a hollow ring for citizens of color across the United States.