(This article is Part III of journalist Ridenour’s political autobiography, Solidarity and Resistance: 50 Years With Che. Click here for Part I and here for Part II)

Grethe Porsgaard and I fell in love, in 1979. She was from Denmark and vacationing in Los Angeles. I traveled to her homeland, in 1980, where we married. At my behest, we made a go of it in her country. A major factor in that decision was that my former wife had taken our children, whose upbringing we had been sharing, from me, and had turned them against me. It would have been a negative way to begin a new love life living close to that madness. Although Grethe and I ended our marriage after several years, we remain friends.

In the first years in Denmark, I worked at odd jobs and wrote freelance, while also participating in Central America solidarity activities. In the course of that work, I met an El Salvadoran guerrilla leader in Copenhagen while he was on tour for the FMLN. We agreed that I would travel clandestinely to El Salvador where I would accompany guerrillas in the countryside, with the goal of writing a book.

This project led to my first visit to Cuba, in the autumn of 1987. My first book, Yankee Sandinistas: interviews with North Americans living & working in the new Nicaragua, had just been published by Curbstone Press in the US. At the recommendation of Cuba’s embassy personnel in Copenhagen, I offered it to Cuba’s foreign book publisher, Editorial José Martí, to publish a Spanish translation.

In a few days, the publishing house director told me that they wished to publish my book and had assigned a translator to it. Delighted, I signed a formal contract. Later, I saw Fidel hold a four-hour speech in the convention center and hung on to every word. It was true what was said about his abilities as a speaker: he was the world’s greatest orator. And what a memory he had! He could start off somewhere and go around the world describing how it was and how it is, and do so without notes or even water, and seemingly all in one long breath.

Just the year before, the government had launched a period of “Rectification of Errors and Negative Tendencies” as a response to economic and political stagnation. The leadership now realized that copying the Soviet Union’s Economic Management and Planning System for 15 years had been a mistake. Rectification was aimed at diversifying domestic production, reducing dependency on the mono-culture export of sugar, stemming market-economy tendencies, and emphasizing volunteer labor.

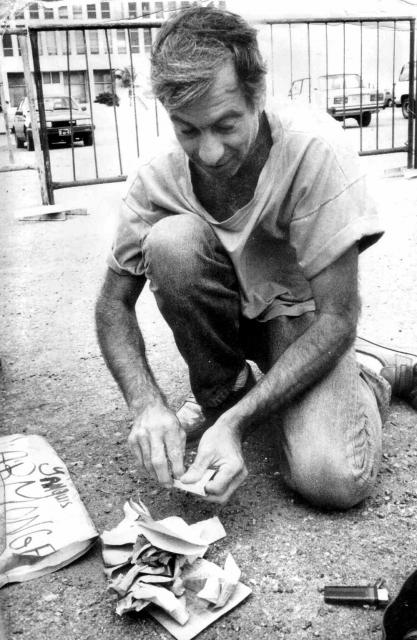

Author Ron Ridenour burns his US Passport in front of US Special Interests Section building in Havana

Author Ron Ridenour burns his US Passport in front of US Special Interests Section building in Havana

On October 8, I traveled with other journalists to Pinar del Rio province, where Fidel inaugurated an electronics factory and held a speech on the 20th anniversary of Che’s capture. We stood for three hours listening to Fidel speak extemporaneously. I was so impressed with this speech, titled “Che’s ideas are absolutely relevant today”, that I quote from it here extensively:

“If we need a paradigm, a model, an example to follow, then men like Che are essential…educating by setting an example… the first to volunteer for the most difficult tasks…the individual who gives his body and soul to others, the person who displays true solidarity…who doesn’t live any contradiction between what he says and what he does…a man of thought and a man of action…”

[“Be Like Che” is the slogan to which Fidel referred during this speech. The slogan was adopted by the Pioneer Exploring Movement, Cuba’s version of the Boy and Girl Scouts. They engage in outdoor activities, explore nature, and do volunteer work.]

“We’re rectifying all the shoddiness and mediocrity that is precisely the negation of Che’s ideas, his revolutionary thought, his style, his spirit and his example…”

“For example, voluntary work, the brainchild of Che and one of the best things he left us during his stay in our country and his part in the revolution, was steadily on the decline. …The bureaucrat’s view, the technocrat’s view that voluntary work was neither basic nor essential, gained more and more ground…We had fallen into a whole host of habits that Che would have been really appalled at. If Che had ever been told that one day, under the Cuban revolution, there would be enterprises prepared to steal to pretend they were profitable, Che would have been appalled.”

“Che would have been appalled if he’d been told that money was becoming man’s concerns, man’s fundamental motivation…the mentality of our worker was being corrupted… he knew that communism could never be attained by wandering down those beaten paths, and to follow along those paths would mean eventually to forget all ideals of solidarity and even internationalism.”

”Che had great faith in man. Che was a realist and did not reject material incentives. He deemed them necessary during the transitional stage, while building socialism. But Che attached more importance—more and more importance—to the conscious factor, to the moral factor…”

“Che was radically opposed to using and developing capitalist economic laws and categories in building socialism…”

“Che’s ideas were incorrectly interpreted and, what’s more, incorrectly applied. Certainly no serious attempt was ever made to put them into practice, and there came a time when ideas diametrically opposed to Che’s economic thought began to take over.”

“The min-brigades, which were destroyed…are now rising again…demonstrating the significance of that mass movement, the significance of that revolutionary path of solving the problems that the theoreticians, technocrats, those who do not believe in man, and who believe in two-bit capitalism, had stopped and dismantled.”

Mini-brigades were composed of workers who volunteered to be relieved of their normal responsibilities for up to two years, in order to build housing, schools and day-care centers. More day-care centers allowed more women to join the work force and volunteer brigades. But soon, with the fall of European socialism, Cuba lost 80% of its international trade and its GDP fell by 35%. Rectification turned into a national campaign for sheer survival—the Special Period in Peacetime—and voluntary work took on even greater steam with volunteer contingents doing farm work. Volunteers worked longer hours than at their normal job. They received the same wage, and the state reimbursed the original workplace for their wages. Although I did not think of it at the time, I came to wonder how Fidel could make such a strong critique of “theoreticians, technocrats, bureaucrats” destroying socialism for “two-bit capitalism” while he was the leader whom everybody knew oversaw all policies. What Fidel criticized then—the thirst for money and consumerism—is even more pronounced today.

Fidel’s praise for the new volunteer workers included medical personnel and teachers traveling to poor countries to cure the sick and enlighten the student. Che, he said, would be proud of these people. Today, Cuba continues exporting this “human capital”, as Fidel calls the volunteers. The United Nations recognizes Cuba as the world’s leading solidarity contributor in these fields. In fact, Cuba sends more medical personnel to countries in need than do the combined countries in the entire UN.

In a December 2008 article commemorating 50 years of the revolution, I wrote, “Today, nearly 100,000 medical personnel, teachers, sports instructors, technicians and advisors are serving in 104 countries. In the medical arena alone, over 10 million people, in 68 countries, have been treated just this decade. Millions of people have been aided in a score of countries hit by natural disasters, such as Pakistan (2006), a US war ally. The new Cuban-created Operation Miracle has cured upwards to half a million blind patients in 25 countries just since 2004. With Venezuela’s oil profits, and Cuba’s doctors and those it is training in Venezuela, the Venezuela-Cuba plan is to cure 10 million Latin Americans within a decade.”

When Fidel ended this speech of criticism of errors, I felt exhilarated. I had a hardbound copy of Yankee Sandinistas with me and wished that Fidel might read it, or, at least, sign his autograph on it. I handed it to a bodyguard to give to Fidel. Four days later, I received notice to collect my book. Fidel had signed it after, apparently, reading through it. I gave another copy to the assistant to give to Fidel for his library.

My contacts in El Salvador got word to me to travel to Mexico and await further instructions. I would slip into El Salvador from there and see what developed. I was thirsty for actually doing something to advance consciousness and to participate in revolutionary action. In Denmark, there was nothing to be done it seemed to me, nothing more than offering a bit of aid to those elsewhere in the world who were struggling. A key difference when it comes to the Danes, who do protest government policies, as opposed to many other nationalities, is a lack of passion to win. In Denmark, people protest perfunctorily, in the main.

I had to wait in Mexico several weeks before I got a message saying to come to El Salvador. Conditions had changed since the time I had made the agreement with the guerilla leader, though. Propaganda about the struggle was no longer a priority. I was asked to do other sorts of solidarity work. Not so enthused about this, I agreed to one short-lived project in Denmark and then returned to Cuba.

Editorial José Marti´s director and chief editor greeted me with broad smiles. They asked me to write a book about 27 double agents (26 Cubans and one Italian resident in Cuba) who had infiltrated the CIA and passed on vital information to Cuban security forces. It would be published in English and Spanish. These men and women had recently been called in “out of the cold”. Very few media in the “first world” were writing anything about it. The agents were all civilians who had other jobs than intelligence work. All had been contacted by the CIA while abroad on their work assignments for Cuban enterprises. They played along with the CIA, agreeing to accept money for information, even to assist efforts to murder Fidel, but then they told their government all they could learn. Apparently a “white man” mentality influenced CIA officials to assume that these “natives” would rather rake in handsome spy fees than be less-well-paid patriots.

The Ministry of Interior’s Department of State Security (DSE) allowed me to interview all the double agents I wished. They also showed me some of their audio-visuals of US spying, and some of the communication apparatuses that the CIA provided their assumed recruits. The two governments did not have official relations, but allowed each other to have interest sections. Many of the US State Department employees in Havana were actually CIA officials, and they tried to control the Cubans in Cuba whom they thought were working for them.

Once I had enough material, I was prepared to return to Denmark and write the book. Then another surprise occurred. The Ministry of Culture, which oversees all publishing houses, offered me a full-time job as a “foreign technician”. I would work at José Martí publishing house as a consultant in the English department, and finish this book and write others. I would be paid a normal Cuban peso wage and live as a Cuban. There were a couple of extras, too. The ministry would find a place for me to live, which would be part of my salary. We foreigner workers had a ration card as did Cubans, but we shopped at special stores with more products on sale, sometimes. Another exception was that we could possess US dollars, which I earned when selling a piece freelance. I used the extra money for traveling abroad.

On July 26, 1993, Fidel told the Cuban people that they, too, could earn and use dollars.

I was overjoyed as I boarded a plane back to Denmark. The publishing house would be sending plane tickets for both of us, but Grethe decided not to move. She preferred to keep her useful job and visit me in Cuba. I wrote most of the book in Copenhagen and then Grethe and I flew to New York City. I wanted US government officials to respond about the infiltration but they stonewalled me. I contacted CBS’ “60 Minutes” TV news program about doing a story on this “worst burn in the CIA history”, as Mauro Casagrandi (the Italian double agent) dubbed it. At first, there was interest but when the US government refused to make any response, CBS dropped the big story.

Back in Cuba, I finished the book, titled Backfire: The CIA’s Biggest Burn, in the fall of 1988. It took two years to come out, which was frustrating for me but Cuban authors assured me that was quick production work for a Cuban publisher. In the meantime, I worked voluntarily at constructing an apartment building and cultivating the earth at a cooperative farm 50 kilometers outside Havana. And I read about Cuba’s economic experiments in the early-mid 1960s.

As Minister of Industry, Che had developed what he called the Budget Finance System (BFS), which competed with the Soviet-oriented Economic Finance System (EFS) being applied in other parts of the economy. The latter was overseen by a former leader of the Moscow-oriented Communist Party, Carlos Rafael Rodriguez. The Soviet economic model was based on monetary pricing, applying the law of value, but as managed by state bureaucracies rather than individual capitalists or private monopolies.

At his most idealistic, Che even made efforts to abolish money, an effort which was too advanced for the times. Furthermore, one state cannot fully create socialism in a world run by capitalism, especially if that state sits on an island just 150 kilometers from the policeman of the globe.

Che was more realistic in much of his endeavor to create an economy that would assure a full stomach and equality for all, eventually ending what Marx and Engels called the “alienation of labor”. This meant implementing equality not only in productive relations—producer/workers as owners with government assistance in coordination and distribution of products—but also equality in overall political and economic decision-making aimed at abolishing capitalist market values and rule.

Capitalist owners allow workers to produce for their use, to varying degrees subject to union power if such exists, but the goal is greater profits for the owners, who set prices and wages. Che’s national budgetary system would set prices as determined on the basis of labor time used and costs of resources and tools necessary to make the product or the service. Che’s idea was that economic planning must reinforce political consciousness. This requires a climate of debate and the organization of schools where workers could improve their skills and study politics, becoming more self-confident and prepared to actually run the economy and eventually the government. The ultimate goal is the “withering away of the state.”

This economic strategy, which incorporated the planned transfer of power to the working class, is a key contribution that Che made to real socialism, one that is not widely recognized. Che’s plan died with his death, just as Fidel said in my citation above. I don’t know what Fidel really thinks about this today, but the 6th CP Congress (April 16-19, 2011) reversed Che’s very concept of a socialist economy/workers power.

Cuba at Sea

In addition to doing volunteer work, I began research on a new book project: sailing with Cuban merchant marines to tell a story of Cuba from the sea. During a two-year period, I worked for six months on three tankers, delivering oil around the island-nation; and then sailed to and from Europe on container ships. These were invaluable experiences and gave me unique insights into Cubans. Unfortunately, a book could not get published in Cuba, as the Special Period curtailed nearly all publishing. Cuba at Sea was eventually published in English by a small house, Socialist Resistance, in England, from which I excerpt a bit here as a teaser:

After I was through with “Backfire,” the editorial director suggested that I experience Cuba as much as I wished and then write a book about Cuba seen from my eyes. I wanted to sail around the island, working and seeing Cuba from seamen’s eyes.

I was on watch with Sigi. He had shown me how to steer helm of the tanker ‘Seaweed’. Sigi was mostly a self-taught man, who had worked many jobs and fought battles during the revolution, although he never managed to join up with the July 26 Movement. He was always frank with me and a kidder too. On one of several voyages together he told me what he thought of life at sea:

“I’ve never liked seamanship, though I’m still a merchant marine after 25 years. I got into it because it was a Communist Party priority. It was necessary to strengthen our shipping capacity, which was next to nil before the revolutionary triumph. Many compañeros took jobs because the country needed them. We were never made to work where we didn’t want to. We were asked and if we agreed then we joined up.”

We were casting off. I responded joyfully and quickly alongside my new colleagues to the boatswain and second mate’s orders, heaving in mooring lines, wrapping the whirling, deadly ropes fast around bitts, cranking in the two 7.5-ton anchors—and we were veering out.

Leon, the boatswain, told me:

“We are one big family aboard ship. We take care of each other. We have a routine, a set time to work, to eat, to relax and to sleep. This helps us stay healthy and organized. This way our ship sails smoothly. It is not just a job but a whole way of life. Here, you lose connection with daily events in the streets, in your home on land. But when you see the news on television or hear it on radio, for instance, that a factory did not make its production goals because its fuel was not delivered when it should have been, you know you are a vital part of society. You know that many plants and people depend upon your work. It gets in your blood. If it doesn’t, you’d better get the hell off the ship.”

I later sailed on the tanker Shark because of its captain. Antonio García Urquiola, who had infiltrated the CIA as a double agent for the Cuban government. The empire’s covert warriors thought it had recruited the Shark’s captain in 1978. The CIA thought they had bought his aid in their efforts to sabotage his country’s maritime economy, even his assistance in assassinating Fidel. Unbeknownst to the pernicious CIA, Urquiola was already ‘Aurelio,’ an agent for Cuba’s state security.

Bright and early on the 4th of July 1990, 214 years after the newly formed United States Congress announced the Declaration of Independence from Great Britain’s colonial power, I swung up a gangway onto the Shark. I was exhilarated, launching into this adventure, the very first citizen of the United States to have been accepted by the Cuban government to board a Cuban vessel. It was a most appropriate day to celebrate, defying the nation of my birth.

I sailed the Cuban container Giorita from Havana to Amsterdam. Midway in the Atlantic I spotted my favorite sea animal…small dolphins were jumping up playfully off the port bow. I snapped photo after photo oblivious to anything else. I swung my left leg over the railing and raised my body up slightly so I could better see the creatures and click the camera.

When I had finished the roll of film, I stepped down onto the deck. I was alone on deck but far away I noticed someone waving to me from the bridge. I walked somewhat unsteadily across the deck as it began to roll more. Up on the bridge, the helmsman spoke to me rather flatly: The captain wishes to see you in his cabin.”

When I arrived at the captain’s cabin his door was shut. I knocked and entered when told to. Captain García spoke immediately.

“What were you doing on deck?”

“I was photographing dolphins.”

“Did you see any seamen on deck?”

“No sir.”

“No, you didn’t, and you won’t for a long time. We’re coming into a storm. Couldn’t you see the swells rising? Are you not clear about the fact that any wave at any time could have knocked you over the railing? You would have drowned with no possibility of rescue. I could have been jailed for your irresponsibility, dammit!”

“I am sorry sir. I’m sorry I upset you. I wasn’t thinking…”

“That’s just great! I can’t risk any mishap aboard ship. You are restricted to the interior for the rest of the voyage. That is all.”

Cuba tolerates no drugs for pleasure

When the biggest scandal in Cuba’s revolutionary history occurred, I called in stories to Pacifica radio, the network of four stations including KPFK. In June 1989, Army General Arnaldo Ochoa, Ministry of Interior General Patricio de la Guardia and his brother, Colonel Antonio de la Guardia Font, and other officers were arrested for misappropriating state funds and operating a drug racket over the prior three years.

The drug scandal was extremely damaging to Cuba. General Ochoa was a genuine hero. He had held the top Cuban military posts in Nicaragua, Angola and Ethiopia. He was close to Fidel personally, and yet Fidel initiated the investigation. This was the first time drug smuggling had occurred since the revolutionary victory, and was especially painful and embarrassing to the president and nearly all Cubans. It is illegal to grow, sell and use any intoxicating drug. And there was almost no drug taking in Cuba, not even marijuana.

The 14 involved in drug smuggling all confessed. After a trial, four were executed within the month; the others were given long prison sentences. The death penalty is rarely used in Cuba, but for this high crime it was employed.

People were shocked and baffled about how such a gruesome crime could be pulled off, given that the executive government exercises as much control as it does, and because of how much the leadership is opposed to drugs.

While I felt discouraged, I also felt that the government had been honest in investigating the crime, in informing the people, and in punishing those in positions of power who had betrayed the nation’s values and laws. I decided to take a long bike trip to Santa Clara, home of Che Guevara’s museum.

Backfire: The CIA’s Biggest Burn

When Backfire came out, December 1990, we held the launch at the Ministry of Interior’s museum, with many of the featured double agents attending. It was a proud moment for me. I quote from the book’s introduction about how the doubles had passed their CIA “lie detector” tests:

I thought of Mauro sitting in front of a polygraph, wired to the cold machine, concentrating on fooling its science. Che’s essay flashed through the picture. He had written:

“At the risk of seeming ridiculous, let me say that the true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love. It is impossible to think of a genuine revolutionary lacking this quality. Perhaps it is one of the great dramas of the leader that he must combine a passionate spirit with a cold intelligence and make painful decisions without contracting a muscle.”

The 27 men and women, who fooled the CIA polygraphs, outwitting Agency elite officers, are the embodiment of Che’s words.

A month after the book launch, I burned my passport in Havana, directly in front of the US Interests Section, in protest against United States’ invasion of Iraq. I acted out of sheer anger and frustration at having protested one US war after another. I could no longer stand being a citizen of the policeman of the world.

My solitary act of protest was covered extensively around the world. I later heard from people who had seen CNN’s report in Europe, Australia, China and other places.

One of my sons sat in his university dorm with his roommate and watched with aggravation and embarrassment as his own father burned the eagle-emblazoned symbol of imperial war. I later heard from my twin sons over the telephone that they did not wish to see me again. Naturally, this response hurt me but it would have happened sometime anyway given that they were being brought up by their mother to worship Zionism and the American Way of Life. I, however, had no moral choice other than to act against these twin evils. I hated being identified with the US-Israel cruelty against other peoples. I didn’t know how I could obtain another passport or how I could obtain another citizenship. In reality, I wanted only to be a citizen of the world, an internationalist. Citizenship to one country is often a nationalist identity, and citizenship in the United States is often associated with warmongering jingoism. For a year, I tried other possibilities to obtain a passport. Cuba was not tactically wise since there would be countries, especially the US, where I could then not travel. And sometimes it might be important for me to do solidarity work inside the monster. I tried Denmark without success, since it would take a year and I had to be living there. Nor would the UN grant me a refugee travel pass. Cuban government officials suggested I try reapplying at the US Interests Section.

I hated going inside the demon’s lair but it was necessary. An embassy official told me that I could apply for a new passport because I was still a citizen, since it turns out one cannot renounce one’s citizenship verbally. One must go to a court in the United States, he said. Months later, I did receive a temporary US passport, which I had to renew on a year-to-year basis, with the stipulation that I not burn it again.

Cutting Cane and Che

Sometimes I would work voluntarily cutting sugar cane–one of the hardest jobs known to woman or man. Add to that the mosquitoes and chiggers who love to suck the cutter’s blood. One of the places I volunteered was one of the oldest plantations, Central Sanguily in Pinar del Rio, the island’s most northern province.

I was fortunate in being assigned to work with a machetero (machete cutter), who had fought with Che in the Congo (Zaire), in 1965. Pepe Arecnio Fuentes came from a part of southern Cuba to which many Africans had been forcibly brought from the Congo during colonial times to work the sugar plantations. When we met, this former guerrilla was 50 years old. He was the quietest Cuban I have ever met. Only after I had won several checker games against him, did he speak to me about his time with El Che.

“I had joined the rebel army just after the revolutionary victory. Sometime in late 1964, some of us were asked if we would volunteer for an `international mission´ that would involve armed struggle,” the muscular machetero confided to me.

“We trained for two months in three different camps. We were curious when we realized that all of us were of the same dark black skin and from the same area. Fidel called us together after training and told us we’d be fighting to liberate Africa and that we’d probably die there. Most of us wanted to liberate the country where our ancestors hailed from. Only two of us stayed behind; 120 went. We had no idea that we’d be led by Che. It was a marvelous surprise when we met him in the Congo,” Karakase (Pepe’s African code name) said softly, spitting on the dirt yet once again.

While the Cuban guerrillas were training, Che was traveling around much of Africa, learning the terrain he knew he would be fighting in. His opinion of many of the various African “freedom fighters” was quite low. Many of them passed their time partying in hotels and brothels.

It was during this period that Che gave his last public speech, on February 24, 1965. He spoke in Algiers at the Second Economic Seminar of Afro-Asian Solidarity, which was attended by representatives from 63 African and Asian governments, as well as 19 national liberation movements. He referred to them all as brothers in a united cause: “the common aspiration to defeat imperialism.” Che made clear his anger at capitalism, at imperialism, and at warped socialism:

“Ever since monopoly capital took over the world, it has kept the greater part of humanity in poverty, dividing all the profits among the group of the most powerful countries. The standard of living in those countries is based on the extreme poverty of our countries. To raise the living standards of the underdeveloped nations, therefore, we must fight against imperialism. And each time a country is torn away from the imperialist tree, it is not only a partial battle won against the main enemy but it also contributes to the real weakening of that enemy, and is one more step toward the final victory.

“There are no borders in this struggle to the death. We cannot be indifferent to what happens anywhere in the world, because a victory by any country over imperialism is our victory, just as any country’s defeat is a defeat for all of us. The practice of proletarian internationalism is not only a duty for the peoples struggling for a better future; it is also an inescapable necessity.

“If the imperialist enemy, the United States or any other, carries out its attack against the underdeveloped peoples and the socialist countries, elementary logic determines the need for an alliance between the underdeveloped peoples and the socialist countries. If there were no other uniting factor, the common enemy should be enough.”

“A conclusion must be drawn from all this: the socialist countries must help pay for the development of countries now starting out on the road to liberation.”

“Socialism cannot exist without a change in consciousness resulting in a new fraternal attitude toward humanity…”

“We believe the responsibility of aiding dependent countries must be approached in such a spirit. There should be no more talk about developing mutually beneficial trade based on prices forced on the backward countries by the law of value and the international relations of unequal exchange that result from the law of value.”

“If we establish that kind of relation between the two groups of nations, we must agree that the socialist countries are, in a certain way, accomplices of imperialist exploitation.”

“The socialist countries have the moral duty to put an end to their tacit complicity with the exploiting countries of the West.”

“For us there is no valid definition of socialism other than the abolition of the exploitation of one human being by another.”

One month after delivering this “tactless” speech, as pro-Moscow Communists saw it, Che was in the Congo. Karakase told me that Che told the Cuban combatants two important things: “We’d have to fight hard and train the Congolese, who knew next to nothing about guerrilla warfare; and we must stay away from the women.”

The most frequent sickness among the African rebels was gonorrhea.

The Cubans were there for seven months. They left on November 18, 1965, feeling they had accomplished nothing. They were distressed at the Congolese for their lack of discipline and frequent drunkenness, their wasting of resources, their laziness and even cowardice. “To win a war with such troops is out of the question,” Che said.

“It was even hard for us to engage in combat, because of their lack of discipline and direction” Karakase explained. “I was only in two combats. In all, we lost eight compañeros. When we left, we sailed over to Tanzania. It was the last time I ever saw Che, and I’ll never forget what he said. He explained that the strategy for independence and justice would continue but that we had to return to our homeland because conditions were not possible for guerilla warfare. Later on, four of those who fought in the Congo went with Che to Bolivia. I stayed in Cuba because I got married. Soon after Che was murdered, I left the army and went into forestry. And for the past 21 years, I have done volunteer sugar cane harvesting.”

Between Che’s disappearance from public sight in the spring of 1965 until his death, he sent a message “from somewhere in the world” to the Organization of Solidarity of the Peoples of Africa, Asia and Latin America. Prensa Latina published it first on April 16, 1967. Here are excerpts:

“How close and bright would the future appear if two, three, many Vietnams flowered on the face of the globe, with their quota of death and their immense tragedies, with their daily heroism, with their repeated blows against imperialism, forcing it to disperse its forces under the lash of the growing hatred of the peoples of the world!

“And if we were all capable of uniting in order to give our blows greater solidity and certainty, so that the aid of all kinds to the peoples in struggle was even more effective–how great the future would be, and how near!”

“Our every action is a battle cry against imperialism and a call for the unity of the peoples against the great enemy of the human race: the United States of North America.

“Wherever death may surprise us, let it be welcome if our battle cry has reached even one receptive ear, if another hand reaches out to take up our arms, and other men come forward to join in our funeral dirge with the rattling of machine guns and with new cries of battle and victory.”

RON RIDENOUR, who was a co-founder and editor with Dave Lindorff in 1976 of the Los Angeles Vanguard, lives in Denmark. A veteran journalist who has reported in the US and from Venezuela, Cuba and Central America, he has written Cuba at the Crossroads, Backfire: The CIA’s Biggest Burn, and Yankee Sandinistas. For more information about Ron and his writing, go to: www.RonRidenour.com