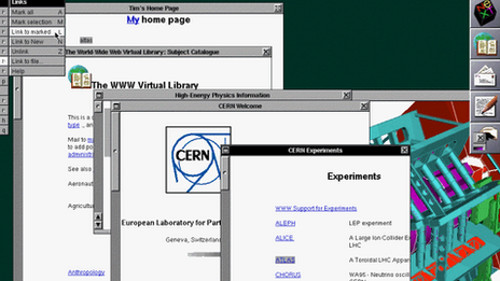

This Summer, a team at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) has undertaken a remarkable project: to recreate the first web site and the computer on which it was first seen.

It’s a kind of birthday celebration. Twenty years ago, software developers at the University of Illinois released a web browser called Mosaic in response to work being done at CERN. There, a group led by Tim Berners-Lee had developed a protocol (a set of rules governing communications between computers) that meshed two basic concepts: the ability to upload and store data files on the Internet and the ability of computers to do “hyper-text” which converts specific words or groups of words into links to other files.

They called this new development the “World Wide Web”.

The Original Web Pages

The Original Web Pages

When you read Berners-Lee’s original proposal you get a feeling for the enthusiasm and optimism that drove this work and, since it’s all very recent, the people who did it are still around to explain why. In interviews, Sir Tim (Berners-Lee is now a Knight) insists he could not foresee how powerful his new project would be but he knew it would make a difference. For the first time in history, people could communicate as much as they want with whomever they want wherever they want. That, as he argued in a recent article, is the reason why it’s so critical to keep the Web neutral, uncontrolled and devoid of corporate or government interference.

In our convoluted world of constantly flowing disinformation, governments tell us the Web is a “privilege” to be paid for and lost if we misbehave, corporations tell us they invented it, and most of us use it without really thinking much about its intent. Very few people view the World Wide Web as the revolutionary creation it actually is.

Whether its “creators” or the vast numbers of techies who continue to develop the Web think about it politically or not, there is an underlying understanding that unifies their efforts: The human race is capable of constructive exchange of information which will bring us knowledge all humans want and benefit from and in collaborating on that knowledge, we can search for the truth. There is nothing more revolutionary than that because the discovered truth is the firing pin of all revolution.

Twenty years later, it’s painfully ironic that, when they hear the word “Internet”, most people probably think of Social Networking programs like Facebook and Twitter. As ubiquitous and popular as Social Networking is, it represents a contradiction to the Internet that created it and to the World Wide Web on which it lives. It is the cyber version of a “laboratory controlled” microbe: it can be and frequently is productive but, if used unchecked and unconsiously, it can unleash enormous destruction, reversing the gains we’ve made with technology and divorcing us from its control.

That’s a harsh picture so some explanation is called for.

You may think the World Wide Web and the Internet are the same thing. They’re not. The Web is to the Internet what a city is to human existence. The first can’t live without the second; the second is extended by the first. But they are not, and never can be, the same.

The Internet is a system of communications comprised of billions of computers that connect to each other through telecommunications lines. It allows people to interact in different ways like email, file upload, chat and, of course, the good old Web.

The Web is a function of the Internet, a kind of subset through which data files stored on a computer (called a server) can be accessed and viewed by people using a special piece of software called a browser. You’re reading this with a browser and your browser is reading this as a file on a server and translating it into what you see. To do that, it uses a protocol called “Hyper Text Transfer Protocol” or “http”. That is what makes the Web special because it produces “hot links” that you can click on to go to any site or page the link creator wants you to. In the links in this article, you go to other web pages and those pages have links of their own. You can keep clicking and deepen your knowledge, broaden your understanding, investigate other connected ideas and get other perspectives on those ideas.

The World Wide Web puts the knowledge and experience of the entire human race at your disposal. With the Web, the human race has finally experienced world-wide collaboration. That, essentially, is the power unleashed by the event that took place 20 years ago.

We can debate the Internet’s contribution to social struggle but there is no question that the era of the Web has seen, among other things: the democratization of the previously dictator-dominated Latin America, the democratic struggles in Northern Africa, the ascendancy of Asian countries as world powers and the resulting democratic struggles those developments feed and, of course, the intense social struggles in the United States that have led to scores of movements, the massive Occupy movement and a black President (probably impossible before the Web).

Compare that to the year 1968 when every continent in the World was awash with resistance and mass movements — fearing a revoutionary over-throw, the government of France actually moved its offices to Germany — and when the culture and social norms of the United States were radically shifted by left-wing activism. Because much going on in the rest of the world was hidden by our corporate-controlled media, most of us in this country didn’t realize it was happening. And so we thought we were all alone and, in that perceived isolation, we were not able to envision the next steps in a struggle to create a just world.

That will never happen again because we now have the Internet. We can envision the next step and we are taking it all the time. The difference is that forty-five years ago, “we” were the people of the United States (or some other individual society). In today’s Web era, “we” are the entire world.

“At the heart of the original web is technology to decentralise control and make access to information freely available to all,” writes the BBC’s superb technology and science writer Pallab Ghosh, “It is this architecture that seems to imbue those that work with the web with a culture of free expression, a belief in universal access and a tendency toward decentralising information. It is the early technology’s innate ability to subvert that makes re-creation of the first website especially interesting.”

How does “Social Networking” jibe with that original intent? To a large extent, it doesn’t.

Social Networking is a marketing term. It isn’t a protocol. It uses nothing new, has added no new technological concepts. It is entirely based on the very same programming the Web has functioned on for two decades. In fact, Social Networking is nothing more than lots of people using some very large websites. But technology’s importance isn’t how it’s built; it’s how people use and perceive it.

People use it…a lot. Last year, over a billion people had Facebook accounts. Twitter routinely logs similar numbers. In short, each of these “services” draw half of all estimated Internet users. There is no question that, in terms of numbers and speed of development, Social Networking is the most successful project in Internet history.

Ironically, the key to Social Networking’s success is a central part of the danger it poses.

Facebook — a group of linked pages on a giant website — is constraining and not very powerful. In order to use it, you have to use it the way they want you to and that’s not a whole lot of “using”. But there is a comfort in having one’s options limited, being able to use something without learning anything about it or making many choices about how you use it. That alluring convenience is a poisoned apple, however. You may not have to learn much about Facebook to use it but the people who own Facebook sure learn a lot about you when you do.

Social Networking is, by its nature, a capture environment. The companies that offer the services, particularly Facebook, host your site and control all the information on it. When you think about what that information says about you, the control is disturbing. CNN writer Julianne Pepitone called Facebook, “one of the most valuable data sets in existence: The social graph. It’s a map of the connections between you and everyone you interact with.”

Not only is your personal data on Facebook but the personal data of all the people you designate as “friends”. In many cases, their photos are displayed (as are yours) showing their faces, the faces of those they come into contact with and the places where the contact took place. There are also long strings of thoughts, comments, reports on what you’re planning to do or what you did and who you did it with. A single web page offers a profile of your life, your activities and your thinking. What’s more, because others “comment” on your facebook pages in an informal gathering of like minds (or social contacts), those connections are condensed.

This amalgamation of information isn’t evil in and of itself. In fact, it could be remarkably empowering. But the problem is that all of it is in the hands of one large company and that company owns it. It will use it in marketing studies and advertising profiles and it will turn that information over to any government agency that asks for it. You have no control over that. It’s in the user agreement. It’s published and it’s no longer yours. It belongs to Facebook and anybody Facebook wants to share it with.

If you want to try to alter what’s presented and how, you can’t. One of the charms and strengths of the Web is your abilility to design and organize your presentations on a website that can easily be unique — showing what you want to show and hiding what you don’t, protecting contact with others through easily created web forms and discussion boards that let people “hide” their real identities, controlling what you share with the world. That can’t happen with Facebook.

Social Networking displays information about you as an individual while restraining your ability to contribute information and thinking about the rest of the world. In fact, its structure often makes that contribution more difficult.

With Twitter, for example, you have 140 characters to make your statement. How much thinking can you communicate in 140 characters? Twitter feels like a room in which a large number of people are shouting single sentences — a lot of noise, even a few ideas but mainly just individualized statements bereft of context, knowledge or the need to exchange perspectives with anyone. Facebook carries so many one-sentence statements that writing anything longer seems strange and even rude.

The incremental “take-over” of the Internet by these programs has one other, even more serious, impact: it’s oppressing people, particularly young people, by repressing their thinking and communication, the very benefits the Web has given us.

The World Wide Web is a classroom without walls, a library in which a library card isn’t needed. Its power of access to so much information is expanded by the Web’s inclusion of you, and every other human being, as a source of information. We not only learn what others think and know from the Web, we are free and even encouraged to add our own viewpoint, knowledge and experiences to that massive mix of information. By adding the hyper-link to this system, its developers have erased national boundaries, combatted cultural exclusivism, battered racism and sexism, smashed into human isolation, gone a long way toward combatting ignorance and expanded our ability to effectively write and communicate.

The seed in the struggle for freedom is the belief that you, as an individual, have value and that your life, as you live it, is of interest and importance to others. That’s a message that is repressed in this oppressive society and keeping that truth hidden is the key to continued oppression. There is nothing more liberating that realizing that your thinking and your experience can be shared with others and that others actually can benefit from it. The Web is the intellectual champion of individual human worth.

But that’s not Facebook and it’s not Twitter. There is simply no way one can share the complexity of one’s thinking or the analysis of one’s life in a one-paragraph Facebook message or a 140 character Tweet. For many young people, the encouraged reliance on these tools of communication, often to the exclusion of the Web’s more abundant capabilities, reverse the impact the Web has had. Used alone, it makes communications shallow, a series of “references” to what the writer hopes others will understand. It is to real discussion what a wink of the eye and poke in the ribs is to honest and revealing communication.

Does Social Networking have a purpose? Absolutely. Some use it to refer to Web pages; it’s an effective means of announcement. Some use it to “stay in touch” or tell others about something happening — as Arab Spring activists used it. It is unquestionably useful.

But those who profit from it push the idea that, rather than a support for the rest of Internet Communications, Social Networking is a substitute for those communications. That is proving very attractive to hundreds of millions of young people and it is increasingly damaging the potential of the World Wide Web for, among other things, real social change.

The debate over its use and impact will continue and my own opinion is certainly not the last word but I know one thing. The people who first developed this marvel we call the World Wide Web didn’t have Social Networking in mind. In fact, what they envisioned (a vision that has come to fruition) is fundamentally different from Social Networking and people who want to change this world need to actively and vigilantly protect and preserve that difference.