If our wars were to make killers of all combat soldiers, rather than men who have killed, civilian life would be endangered for generations or, in fact, made impossible.

– J. Glenn Gray, from The Warriors: Reflections on Men in Battle (1959)

I lost myself when we busted down that door.

I lost myself. Please don’t make me tell any more.

– Tom Mullian, from “Private Charlie Mac”

Why can’t we all just get along?

– Rodney King

According to a New York Times report on Memorial Day, psychologists are re-thinking Post Traumatic Stress and other combat-related issues applied to multi-tour combat soldiers. According to Times writer Benedict Carey, the challenge these days is less emotional healing than how to unlearn the hyper-vigilance and shoot-first, ask-questions-later violence necessary for survival in a combat zone. That is, using the current vogue term, can experienced warriors be adjusted from a wild, adrenaline-fueled state of barbarism to one emphasizing community and civilization?

An aging Stephen Seagal in a new movie, Sniper: Special Ops, and a classic home and family image

An aging Stephen Seagal in a new movie, Sniper: Special Ops, and a classic home and family image

This is a politically tricky matter, since this sort of question inevitably leads to areas critical of US war policy. It’s notable that the research cited by the May 30 Times story is being done in civilian universities (Harvard, the University of Texas, the University of New Haven, the University of North Carolina) and other civilian research sites — not by the military or the Veterans Administration, federal government agencies naturally reluctant to wade into anything that might be critical of US war policy. The veteran at the center of the Times story is an ex-Ranger whose unit specialized in what the Times reported is sometimes known as “vampire work,” quick raids, often late at night, on high-profile insurgent targets for capture or killing. Just the term “vampire work” suggests the experience being considered is morally ambivalent.

A New York Times Magazine article on June 12th titled “Aftershock” took a different tack. Writer Robert F. Worth reported on new studies by military-connected researchers that suggested to him what we think of as PTSD might be less “emotional” and more “organic.” The story’s promo line asks: “Could PTSD turn out to be more physical than psychological?” The story treats new research on traumatic brain injury as some kind of watershed discovery questioning the psychological focus of PTSD on issues like bad memories that don’t sit right in a veteran’s mind and what is known as the “moral wound.” On one hand, the article says the matter is complex, while the writing and headlines heavily emphasize the focus on physical damage as a major cause of PTSD.

Worth is an experienced Middle East correspondent with a new book on that region called A Rage For Order that has received glowing reviews. Two of these reviewers said the book described a “Hobbesian” world descended into ethnic and religious factionalism, a world that the US military has been inserted into for decades, often in a very destructive and even contradictory manner that exacerbates these Hobbesian conditions. Add to this the often hysterical follow-up to the Orlando massacre and the mix becomes extremely volatile. A well-armed, mentally-unbalanced Afghan-American kills 49 bar-goers and tells a 911 operator he’s working for ISIS; he also says he’s loyal to al-Qaeda and Hezbollah — Sunni and Shia organizations at odds with each other. The militarist right see this as evidence of a war climate. They beat the drums for more military action and bombing against ISIS in Iraq’s Anbar Province and Syria. President Obama is blamed for ISIS, and the right argues the occupation of Iraq should be permanent. The fact ISIS was created as a direct, vengeful reaction to the US invasion and occupation of Iraq in Sunni Anbar Province is lost in the Hobbesian madness.

Thomas Hobbes was a 17th century English political philosopher who believed in a brute basis for life and the need for a social contract necessarily enforced by violence. Here’s a famous passage from The Leviathan:

“In such condition, there is no place for industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving, and removing, such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

The conservative African American philosopher Thomas Sowell in A Conflict of Visions very neatly breaks down the political struggles in America. He sees it as a struggle between two basic visions: the constrained and un-constrained. The constrained visionaries include those like Hobbes who see life as brutish and those like Adam Smith who see moral values as a trade-off from the rule of self-interest and a free market. The un-constrained vision is rooted in the likes of Jean Jacques Rousseau and William Godwin; they see humanity as perfectible — or in the spirit of the current term, “progressive.” Progress is possible. In other words, a moral, decent society is not a matter of “trade-offs” from self-interest, but a matter of determined decisions and actions. Sowell sees the struggle between these two political visions as a continuum: “[I]n the real world there are often elements of each inconsistently grafted on the other, and innumerable combinations and permutations.”

We see this left-right political struggle played out every night between MSNBC and Fox News — where there is no middle-ground. The two Times stories on PTSD suggest a struggle based on these vision is being opened with PTSD in this election season. As is said of the writing of history — that it’s written by the winners — applies to PTSD. What war-trauma means is necessarily wrapped up with politics and whose stories will prevail. If endless Hobbesian wars of factionalist violence is seen as our current (and future) reality, the military’s motivation for avoiding discussion of moral consequences from war is clear. The military’s policy of resilience as a counter to trauma makes sense in this view. Get the trooper back on the line. In a brutish, Hobbesian world, survival and military success revolve around power and violence, and the idea of a moral wound becomes a frivolous indulgence — a weakness. It’s not surprising military researchers might emphasize the physical, while civilian researchers might focus on a more optimistic, cooperative basis for humanity. On one side, the consequences of brute violence to morally-fragile human beings is a matter of effectiveness, while on the other, the same consequences are a hurdle to encouraging productive, civilized communities.

Veteran Runs Amok 2400 Years Ago

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and the difficulties of war-fighters re-adjusting to community life back home is not a problem unique to an American culture faced with returning combat veterans from places like Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan. In fact, it’s an ancient issue. Wars deemed necessary by political leaders have always had repercussions on the individuals sent to fight them.

The Greek playwright Euripides was a military veteran of the Peloponnesian Wars between Athens and Sparta when he wrote a play titled Herakles around 421 BCE. Robert Emmet Meagher has translated the play and written commentary on it in a book titled Herakles Gone Mad: Rethinking Heroism In an Age of Endless War. Meagher has a polemic purpose and suggests the city-state culture in Athens was suffering a form of societal trauma our modern culture would benefit from thinking about.

When plays like this were performed in public, Meagher says, most of the men in the audience had, like Euripides, fought in terribly bloody battles against the rival city-state of Sparta. Meagher cites Judith Herman’s book Trauma and Recovery and her “three stages of recovery.” He says the mythic nature of the Athenian theater provided veterans and their families a public context of 1) safety, 2) remembrance and mourning and, 3) re-connection in which to consider larger questions of barbarism and civilization. Freud might have framed this as a struggle between Eros and Thanatos, the social forces of life and death he wrote about in the years after WWI.

Meagher’s effort is a response to writers like Victor Davis Hanson, an authority on the Greek war culture of the time. In 2002, Hanson published Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise of Western Power and, in 2004, Between War and Peace: Lessons From Afghanistan and Iraq. “What I find particularly alarming,” Meagher writes, referring to Hanson’s work, “are the violent mantras that he claims to have derived from his studies and his involving of them over the past several years to help plunge America into two wars.” Hanson is instrumental in the establishment of a historic and mythic framework for the post-911 warrior ethos that now pervades our culture from special ops to local militarized police departments.

Herakles is not an easy drama to stomach today; it was likely so even in 421 BCE. Meagher says it’s often overlooked as “a wreck . . . rarely if ever produced and seldom studied.” Meagher sees it as “the voice of a weary and wise warrior, who may have fought his last battle but whose labors have only begun.” Meagher points out that Euripides received fewer civic prizes than other Greek playwrights. “He hated war, but loved the warrior. … He loved Athens, but hated her politics. … He reconciled his patriotism with fierce and loyal dissent and paid the price.” He died in exile.

Herakles, of course, is a mythic hero, the son of Alkmene from a rape by Zeus. The play is fiction. Herakles is returning from war and the underworld where he rescued his warrior friend Theseus. His homecoming is complicated by a bloody intrigue from Lykos, a usurper who has killed Kreon, the ruler of Thebes, and his family. Lykos plans to kill the rest of the royal family, including Kreon’s daughter, Megara, who is Herakles’ wife. With so many men off to war, Herakles finds “a curious dearth of able-bodied men” in the city. He, thus, assumes the labor of killing Lykos, an action he undertakes soon enough. Here’s how Meagher describes what happens:

“Then something goes wrong. In fact everything goes wrong. Herakles suddenly turns on his own family and savagely slaughters them; and the only explanation given is that Lyssa, insanity personified, has descended on the house and loosened Herakles from his wits, driven him clear out of his mind.”

Critics of the play say, at this point, “it snaps in two with the appearance of Madness (Lyssa). From that moment, we are arguably left with two unrelated dramas: one a triumphant homecoming, and the other a domestic disaster.” Meagher says, on the contrary, the two parts work incredibly together, and Euripides is in fact up to something quite serious — maybe something considered a bit subversive.

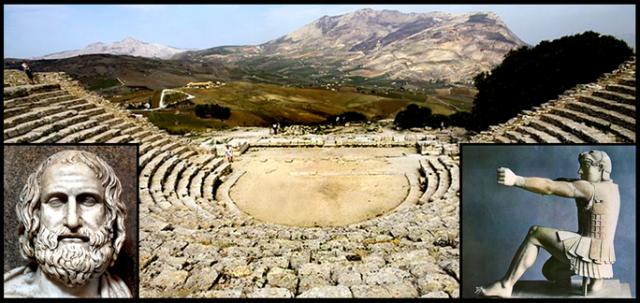

Ruins of an ancient Greek theater, a bust of Euripides and the hero Herakles

Ruins of an ancient Greek theater, a bust of Euripides and the hero Herakles

“All the principle risk factors for post-traumatic stress, indicated by today’s psychiatric specialists,” Meagher writes, “were present, even rampant, in the war between the coalitions led by Athens and Sparta: morally suspect mandate, unclear mission, civilian slaughter, torture and murder of prisoners, rape and atrocity, massacres driven by rage and revenge.”

At Herakles’ homecoming, Euripides has a chorus of old veterans sing Herakles’ praises: “Your life-exhausting labors, ridding the world of our most feral fears and demons, have given to the rest of us a less troubled life.” This, of course, is the core idea behind our current warrior ethos.

Iris, a messenger from a jealous Hera, wife of Zeus, enters the stage with Lyssa, the embodiment of madness. Iris orders Lyssa to “Madly churn [Herakles’] soul until it swirls in confusion and seethes with child-slaughtering fantasies.” Lyssa reluctantly does the deed, and Herakles, in a berserk rage focused on the usurper Lykos, then proceeds to kill his wife and children. An observer/messenger tells the tale: “He was no longer himself.” “Herakles stalked the halls of his own house.” “[H]e wrestled furiously with an unseen opponent.” “[H]e mounted a chariot that wasn’t there.”

The messenger’s account ends with, “If there is a more miserable man anywhere I don’t know who he could be.” Herakles goes into a suicidal depression. “How short of death can I outrun the shame and infamy that awaits me?” he cries.

At this point, brother-in-arms Theseus shows up and tells Herakles, “Men of your blood and stature stand and hold their ground in whatever winds the gods send against them. They don’t quit.” In other words, though your dark, delusional actions have caused ruin to that which you love, your life is not over: You still have much to contribute to your society.

The play ends with the two men retreating to Theseus’ home, where we are led to believe Herakles will over time be healed. It’s an ancient Greek play, so there’s no media blame culture or criminal justice system to deal with. Jealous Hera conveniently gets the rap for causing Herakles’ madness. Again, this is a safe, public space of myth and ideas where very difficult issues can be dealt with. Meagher opens his commentary by quoting the ancient Greek philosopher Heraklitos: “ ‘The unfolding nature of things is wont to conceal itself.’ Truth likes to hide. And, alas, we like to hide from it.” Euripides’ play is, thus, a device to ferret out the hidden “nature of things” inside the minds of the audience.

This type of theme plays out in modern drama, as well. The other night, I watched the 1971 film The French Connection, a gritty portrait of an obsessed New York narcotics cop in the early days of The Drug War. Gene Hackman as Popeye Doyle is not a military man, but he’s a classic warrior character; his intense focus on mission would transfer nicely to a post-911, anti-terrorism police and military mindset focused on al Qaeda and ISIS lone wolves. Unlike Herakles, Popeye has no literal family; he has a professional family. The adrenaline excitement of hunting “dirty” guys is what his life is about, no matter the cost in destroyed cars “borrowed” from passers-by, near-misses on mothers-with-baby-carriages or, in the end, the fatal shooting of a police partner — albeit a cop who disliked him and taunted him about his intense, reckless nature that resulted in an earlier death of another detective.

An ancient Norse warrior fighting in a frenzy was known as a berserker. Both Herakles and Popeye Doyle kill unintended people close to them in a berserker frenzy. Friendly fire and collateral damage are the euphemisms we use these days for these kinds of unintended victims of violence. Sometimes it can strike very close to home. Due to a friend’s understanding and intervention, Herakles will be healed and become part of the community. Though his French drug-supplier target gets away scot-free — he fails in his mission — due to the institutional understanding of the NYPD, Popeye is taken off the narcotics squad and moved to another assignment. Neither Herakles nor Popeye faces formal consequences for their actions; any and all consequences are internal and psychological.

From the Wild Zone to Community

Besides any potential critique of US war policy, the Times story on multi-tour combat soldiers adjusting to life back home gets close to touching the third-rail of anti-war-movement political etiquette — the rule that says it’s OK to criticize the war but not the warrior. Much of this etiquette question depends on who’s talking about the problem: Are they friendly to US war policy or are they critical of it? In his play, was Euripides critical of Herakles or was he critical of the wars that had contributed to making Herakles run amok? Or was he just representing reality as he saw it in a courageous artistic fashion?

“The military is very good at identifying and amplifying the psychological factors that make a high-performance fighter,” Benedict Carey writes. “The Pentagon has spent hundreds of millions of dollars on testing and analyzing these elements, but its researchers publish very few of their findings and refuse to speak in specifics on the record.” The rigid regime of secrecy that controls information on military and intelligence agency activities also means these institutions are tight-lipped about their research into the act of killing; clearly, the military has a real incentive to make killing more efficient and effective.

Reported in 2003 in On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society by Lt. Col. Dave Grossman, all sorts of research has been undertaken on how to better get a man or woman to kill another human being. Grossman examined the record and history and found that the average person is reluctant to kill. The Pentagon is in the leading edge of this research. How to overcome that natural human reluctance to kill and what kind of person is best suited for the task has become a field of knowledge, which Grossman has awkwardly dubbed killology.

This encouragement of an effective killer mentality works both ways in our “Hobbesian” wars. The much less sophisticated but, nevertheless, equally hyper-vigilant and hyper-masculine mindsets of trained fighters in organizations like al Qaeda and ISIS no doubt, like our military, work at improving their capacity for killing, since grotesque ruthlessness has become one of their strong suits. In light of Martin Luther King’s idea of a widening gyre of vengeance and violence, this becomes a formula for self-generating, endless war. If you consider the misogynous elements of our Middle Eastern enemies and add the notion that in intense mortal combat one necessarily must assume some of one’s adversaries’ ruthless qualities in order to prevail over them — you’ve got the recipe for serious problems when experienced veterans of this kind of combat try to adjust to the social contracts of domestic, community life back home.

Another tricky political implication of the Times story is how it relates to members of local, state and federal law enforcement agencies. Many multi-tour combat veterans end up in these jobs. Arguably, this revolving-door reality contributes to the further militarization of our police forces and the tight relationships connecting federal military and police institutions with their local counterparts through things like the many regional and urban fusion centers sprouting up across the nation. Language matters. What, for example, are the implications of the fact the police unit covering the African American community in Cleveland where 12-year-old Tamir Rice was shot and killed was called a Forward Operations Base (a FOB), the term of art for bases in Iraq and Afghanistan?

Fictional cop Popeye Doyle going berserk hunting a badguy and a billboard in Chattanooga

Fictional cop Popeye Doyle going berserk hunting a badguy and a billboard in Chattanooga

Mass incarceration and police killings of African Americans like young Rice led to the Black Lives Matter movement, which has become a left/right political flashpoint that has spawned a reaction among police known as the Blue Lives Matter movement. Huge blue billboards outside areas like Philadelphia and Chattanooga ,Tennessee, feature a gold badge and the words BLUE LIVES MATTER. Cops are encouraged by the political right to feel cornered and to close ranks. Last month, Louisiana’s governor signed a “Blue Lives Matter” bill that made police officers a protected class under hate-crime law. The irony is that hate crime laws were designed to help powerless, abused minorities, not one of the most powerful lobbies in America whose members consistently seem untouchable by the law. Add to this beleaguered sense among cops the cancerous problem of secrecy among the federal-to-local institutions of military and police and it’s easy to see how the concept of “community” policing itself is considered by many to be on the ropes.

Dr. Charles A. Morgan III, a psychiatrist at the University of New Haven who has worked with special operations veterans, told the Times that the well-adjusted, civilized person “takes in information and then retreats into their head and wants to think about it, then maybe checks the environment again and thinks some more.” Not so with a well-trained, multi-tour combat soldier in today’s military, he says. He or she is trained to “make a quick decision — then act and adjust as they go.” It’s not very flattering, but that smacks a lot of “Shoot first, ask questions later.” One of the veterans the Times writes about is frank about this. He’s described as a tough man, always driven to be out in front ready to make things right. He rages at bad drivers and litterers, people who upset him by doing, or not doing, something. He wants to confront them and straighten them out. “You react — and next thing you know, the police are there,” he says. This veteran is lucky; he has a supportive family and friends who have helped him “see the humanity of the people I was confronting.” Others are not so lucky; and some of them are wearing police uniforms.

The question is an ancient one: What’s “normal” and who decides? Is the dangerous, Hobbesian context of war requiring hyper-vigilance, quick thinking and very violent reactions normal? Or is normal a more civilized state of being, about family and job and cooperation with a diversity of people in pursuit of community and a cooperative social contract? The struggle will go on.

In The Hurt Locker, the protagonist is a de-fuser of bombs in Iraq; he’s incredibly brave, very good at the job and highly respected. When he goes home, he’s lost like a fish out of water. At the end, following a scene of alienation in a grocery store, he’s back in a cumbersome bomb suit in a dusty street in Iraq — “at home” again. How does society get a character like this to want to be with family members and non-veteran friends? To want to work at a job that doesn’t trigger adrenaline but satisfies something less violent but equally as rewarding. And, finally, how do we get our hypothetical multi-tour veteran to better accept others unlike himself as the secret to living in a community with others — not because he’s ordered to, but because diversity, difference and complexity are good, healthy things.

In The Women of Trachis, the Greek playwright Sophocles has Herakles returning to a wife named Deianeira. In his commentary, Meagher says, “Warriors . . . live on the edge of the human circle. . . . And when the warrior returns, he all too often brings the wild back with him.” Deianeira is torn: “Which is worse, having a husband at war or having a warrior at home?”

In the Euripides play, Theseus stops Herakles from killing himself and opens a healing path. Meagher puts it this way: “[T]he full narrative of Herakles’ trauma must and will be reconstructed . . . . [It] is an essential therapeutic element in the healing of trauma.” The horrific facts can’t be changed, but what they mean for the future can be “reconstructed.” Theseus tells his comrade-in-arms acceptance and courage are what’s required. “Compassion is the oxygen of any community worthy of the name,” Meagher writes. “War is undoubtedly hell, but the peace that follows can be an even greater hell for the warrior.”

There is only one place to end this story and that’s in the arena of politics, where the real sorting out of these narrative struggles is undertaken. Meagher subtitles his book Rethinking Heroism in an Age of Endless War. The new, re-thought hero that would help open a path to healing for this torn nation is the hero who stops trying to argue that our debacles of war were patriotic necessities rather than tragic stepping-stones for further cycles of vengeance and violence. It’s true, we need to better respect and honor our wounded veterans; but we also need to understand that “the wild” brought back by multi-tour combat vets from the “edge of the human circle” is not constructive for community or for civilization itself.