In the most recent issue of Neurology, Dr. Altaf Saadi and colleagues reveal the disheartening news that African Americans and Hispanic Americans receive lower quality neurologic care than their white counterparts.

Analyzing data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey from 2006-2013, they found that Black patients were 30% less likely to see an outpatient neurologist even after adjusting for social factors such as insurance coverage. Hispanic patients were 40% less likely.

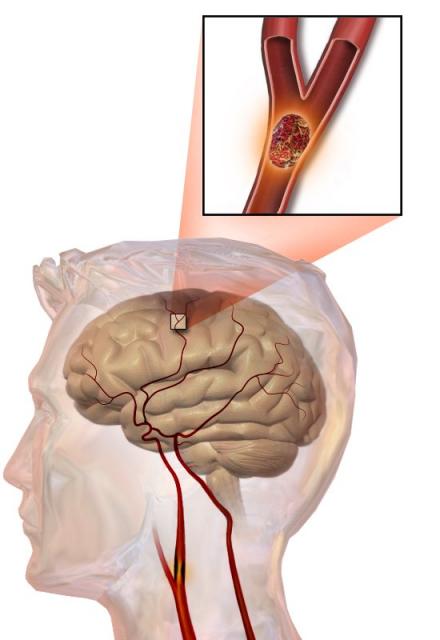

They looked at neurologic diseases such as stroke, headache, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and epilepsy. According to the CDC, strokes kill over 130,000 Americans each year, about 5% of deaths. Strokes are also the leading cause of long-term disability. Furthermore, the risk of stroke is nearly twice as high for Black Americans as opposed to whites. Yet, despite higher rates of stroke, Black Americans are seeing neurologists, the experts on strokes, less.

The authors postulate that there are likely simultaneous factors. The first factor they cite is low health literacy. Not only are patients unaware of all the possible follow up care that can prevent another stroke or minimize the impact of a recent one, folks might not even recognize the symptoms of stroke, multiple sclerosis, or Parkinson’s disease to begin with.

Folks of color are more likely to have their care across more than one healthcare system making it difficult for the primary care doctor, the emergency room doctor, the neurologist, and the hospital doctor to coordinate their care. If you live in the Southeastern United States, the number of neurologic specialists is far lower than anywhere else in the country.

And finally, the impact of implicit bias and stereotyping cannot be underestimated. Though most doctors are well intentioned and would like to be “color-blind” study after study has shown that we have also absorbed the subtle messages that society sends us that folks of color are inferior or less deserving of care. As this study points out, even at high volume specialty sites, Black and Hispanic patients get delayed care compared to whites.

But perhaps the most distressing part of this article is that time and resources were put towards it at all. We already know that Black Americans, Hispanic Americans, Asian Americans, get lower quality care and that they die younger because of it. David Hatcher, former Surgeon General reports that from 1991-2000, 880,000 excess deaths could have been averted had the health of Black Americans matched that of whites.

In fact, we’ve known this for almost 15 years. In 2003 the Institute of Medicine published a 764-page report that reviewed hundreds of studies. In the report, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, they found that even when controlling for factors outside of the hospital system (insurance coverage, location, severity of disease, socioeconomic status etc), disparities remain. The bottom-line? Not only does racism on a societal level cause people of color to have worse health outcomes, so do the unconscious biases of those working in the healthcare system.

In fact, Unequal Treatment already looked at stroke outcomes.

We don’t need more studies showing that there are racial health inequities. We already know they exist. The authors of this study assert that this study is groundbreaking because it’s the first “nationwide stud[y] examin[ing] disparities in the use of neurologic care for people with a broad range of neurologic conditions.”

Why would there be any reason to think that this data would be any different than the hundreds of similar studies about race and medicine that have been done before? Furthermore, when it comes to naysayers, why would one more study help them understand if the hundreds of studies before didn’t in the first place?

Instead of spending precious resources on re-proving what we already know, we should be spending it on trying to address the problem. In fact, implementing projects to close these racial inequities are quite difficult. While many attempts frequently improve outcomes overall, they do not impact the gap at all. Some even act to increase the disparity.

For example, we know that colonoscopy rates are lower amongst people of color. One intervention to try to address this is to send electronic messages or letters to patients reminding them when they are due for colon cancer screening. The problem with this is that it doesn’t help my patients who don’t speak English and don’t have access to the internet. At the same time, my white patients will find this useful at a much higher rate. While the intervention might improve colonoscopy rates across both groups, it will improve it more in the white group, thus actually making the disparity larger.

Addressing health inequity is not an easy task. Research is supposed to help us solve problems that we don’t know how to fix not tell us stuff we already know. We would be better off spending research time and money on finding solutions as opposed to “rediscovering” the same problem over and over again.