The great leaders of the United States Navy finally made their decision about the fate of the skipper of the aircraft carrier Theodore Roosevelt. This was apparently a hard one for these men — too much humanity and courage openly at play. They shuffled around and sputtered very uncomfortably for a while, went back on themselves and said Captain Brett Crozier was going to be reinstated to his command. Then — wait a minute! Never mind. They needed to go into consultation in a Maxwell Smart cone of silence deep in the Pentagon.

Figuring enough time has elapsed that most people have forgotten the embarrassing episode, our stalwart Navy leadership has now made a final decision:

To the tune of Anchors Aweigh, they tossed Captain Crozier overboard.

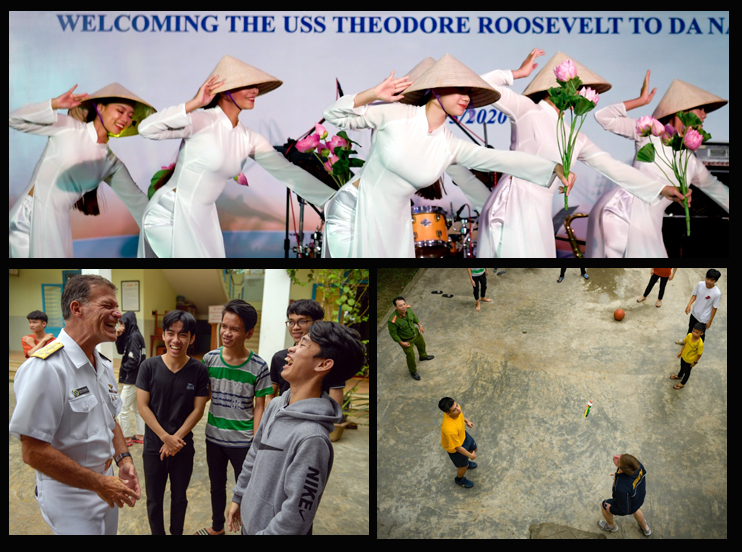

[The Theodore Roosevelt arriving in Da Nang harbor in early March.]

The Theodore Roosevelt’s early March five-day, port-of-call visit to the Vietnam city of Da Nang was where its sailors picked up the virus that, then, swept through the huge ship’s close quarters. It was not the Vietnamese’s fault; shit happens. The leadership’s final decision makes it clear the huge warship’s 21st century gunboat-diplomacy mission in the Pacific Ocean and South China Sea trumped all concern for the lives and safety of the sailors on board. In the spirit of the ship’s namesake — Big Stick Teddy Roosevelt, the nation’s beloved original imperialist — the leadership’s top priority is to show the flag to scare the Chinese, the health and welfare of our sons and daughters in uniform be damned. Maybe Captain Crozier should have slipped his dead crew members off the fantail wrapped in Old Glory — like in the WWII war movies.

[Carrier crew members at work; Captain Crozier, and crew members vocally sending him off with love and respect. At bottom, Chief Petty Officer Charles Thacker, Jr., who died of COVID19 April 13th.]

We all know the sorry tale of how the “interim” secretary of the Navy, a career hack named Thomas Modly, fearful of Boss Trump’s wrath, fired Captain Crozier for an email he sent to fellow officers expressing his exasperation dealing with Navy command as COVID19 broke out on his ship. The skipper sent the email fully aware it could nix his expected promotion to admiral and end his Navy career. The welfare of his crew foremost in his mind, he did it anyway.

Upset at all the press coverage, an irate Secretary Modly got on a plane and flew halfway around the world to Guam to bloviate on a microphone through the ship’s loudspeaker system calling Captain Crozier “stupid” and other abusive things to the man’s crew. Earlier, as their relieved skipper walked down the gangplank of his ship, hundreds of crew members gave him what can only be called a robust, loving farewell. One can easily imagine the one-finger salutes and the choice words expressing where the secretary could stick his rant that must have spread through the ship as his irritated voice sounded off like those absurd loudspeaker announcements in M.A.S.H.

You can’t make this stuff up; it was so dramatic the story went viral. Soon, Modly was forced to resign, his career relegated to a shameful footnote in the dustbin of history.

THE NAVY GOES TO THE MOVIES

The Navy was big in my childhood. I was raised by a PT boat captain who had served in the south Pacific and indoctrinated his three sons during the 1950s by taking them to watch Navy movies. A thorough cinephile, the Theodore Roosevelt incident reminded me of those movies. Two of my favorites are about good and bad shipboard leadership. A third is about the ruthless intelligence of command during wartime.

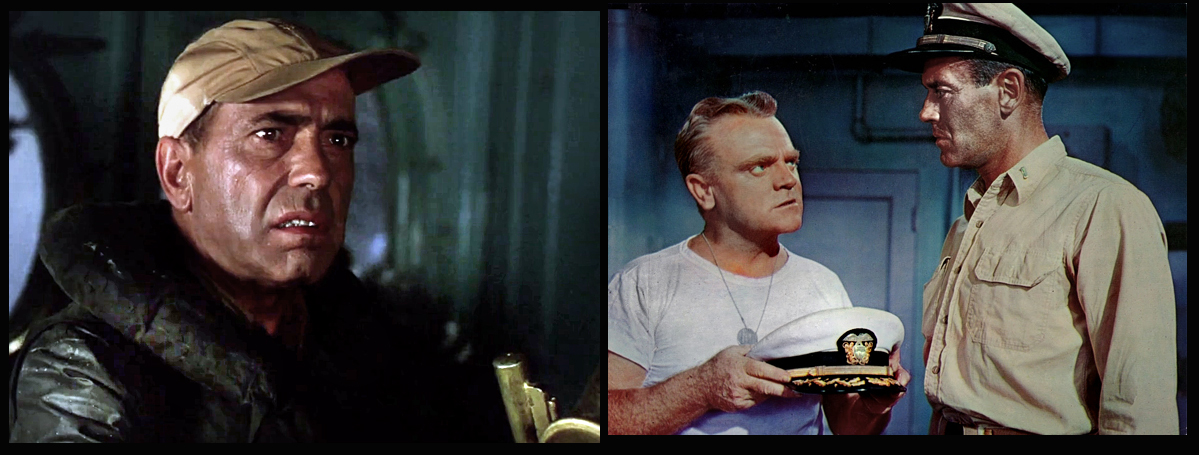

My father loved Mister Roberts, a 1955 tragicomedy smash hit novel, play and film about a supply ship — known as “the bucket” — on the periphery of the war in 1945. The captain is played by James Cagney as a man whose lack of competence and low self-esteem add up to terrible, resentful leadership in search of a promotion to commander. Henry Fonda is Mister Roberts, the ship‘s cargo officer, the good leader who cares for, and sees his mission as looking after, his crew, men who have spent a year on the ship with no shore liberty — men who are “going Asiatic.” The crew respects Roberts, but he’s unhappy and longs to be in the war. “The war is passing me by,” he tells Doc, a wise and witty, older ship doctor who’s also loyal to the crew of enlisted misfits. It’s a comedy, so what stands in for a “mutiny” is played for laughs in the form of a fed-up Mister Roberts throwing the captain’s potted palm tree over the side. The ship won the palm tree for, as Roberts puts it, “delivering more toilet paper and toothpaste in the safe areas of the Pacific.” Tossing the captain’s palm tree over the side makes the crew love Roberts even more.

Each month, the captain denies Roberts’ request for transfer to a combat destroyer. Roberts agrees to a deal with the captain to obey him like a dog on a leash and stop sending in requests — if the captain agrees to give the crew a liberty. This sets up the second mutinous event. When the crew finds out about the deal, since Roberts can’t send in any more requests, the crew sends one in themselves, forging the captain’s signature at the bottom. Spoiler alert, the film ends tragically when the crew learns Mister Roberts has been killed on his destroyer by a kamikaze as he was absurdly drinking coffee in the officers’ mess. As a quite anti-military sort of person, I’ve seen the movie maybe four times; each time I watch it, these last scenes always tear me up.

[Captain Quegg freezing up in the typhoon; the captain with the field grade officer’s hat he covets and Mister Roberts having it out. “How did you ever get into the Navy?” Roberts asks.]

The Caine Mutiny is another classic I’ve watched several times; it’s from a popular fifties novel by Herman Wouk. This time it’s Humphrey Bogart playing the incompetent leader of a minesweeper, Captain Quegg, a man who’s self-doubt and mental instability under pressure almost dooms the USNS Caine in a typhoon. The captain freezes in the storm, and the second in command takes over the ship to save it and its crew. There’s a court martial in which the captain’s mental state is questioned; also questioned are the mutineers, who are accused, because they disliked the eccentric Quegg, of failing to support him in a crisis. In the end, Quegg, who’s always rolling steel ball bearings around in his hand, damns himself before the court martial by making it clear he’s lost his marbles. To get the Navy support needed to make the film, the movie opens with a statement that there has never been a mutiny on a US Navy ship. In the case of Mister Roberts, the Navy was reluctant to support the film because it showed rotten leadership; but its director, John Ford, had worked with the Navy and the Office of Strategic Services (the predecessor of the CIA) as a filmmaker and eventually became a reserve admiral. So he had the necessary pull, and the film got Navy support.

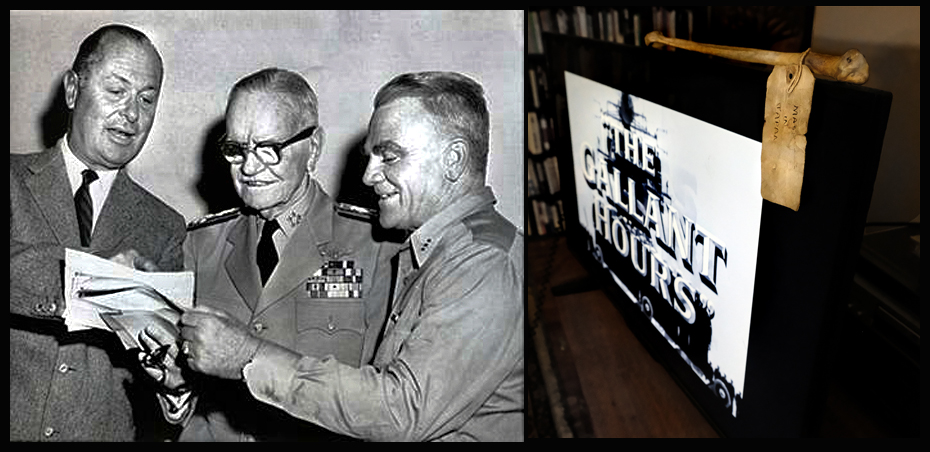

Finally, there’s another Cagney movie about Navy leadership that I can never forget from my childhood. The Gallant Hours is a 1960 docudrama focused on Navy Admiral William Halsey, better known as “Bull” Halsey. (He reportedly got his nickname due to amorous exploits while a cadet at Annapolis.) The film follows the admiral during the battle for Guadalcanal and was directed by the actor Robert Montgomery, who himself was a PT boat skipper and later commanded a destroyer during D-Day. As for the leadership theme, the Halsey movie is unabashed worship of a leader men like my father revered. Alas, it’s not a film with any lasting dramatic power.

[Director Robert Montgomery, the real “Bull” Halsey and Jimmy Cagney; and Dad’s “Jap bone” on my TV as I recently watched The Gallant Hours.]

I recall Mom and Dad and the three Grant boys sitting down to watch the Halsey movie, the beautiful wood and brass wheel from my dad’s PT boat on the wall to the right of the black and white TV set in our concrete-block, flat-roofed house in south Dade County, Florida. Like many soldiers and sailors in WWII, my dad sent home a trophy, in his case, a fibula leg bone cut from a rotting Japanese corpse on the island of Peleliu. He hung it on a rope below his boat so the fish could clean it; then, he sent it home to his mom addressed to Ink, her black cocker spaniel. He kept it in his desk drawer with a yellow manila tag, on which he’d written Made In Japan. As the credits began for The Gallant Hours, in his ragged shorts and rotten sneakers, ex-Navy Lieutenant Wilson Grant mischievously tip-toed into his desk and came back with the bone, which he carefully set atop the TV, the end of the manila tag slipping over the edge of the TV. He, no doubt, reminded us during the movie how when he’d drive his PT boat out of Guadalcanal harbor he’d always pass by a huge billboard with bold letters that read:

KILL JAPS!

Admiral Halsey

There’s no leadership conflict in this film; the enemy isn’t boredom, military “chicken shit” or even fear: It’s Japs. This was no-holds-barred war against a demonized race of people who had invaded the United States in a sneak attack. The war had established a state of mind in my father. He was scheduled to drive his PT boat into Tokyo harbor on the final assault on Japan, something he did not want to do. To anyone who questioned Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he would reply, “What did they expect?” The problem with my father, may he rest in peace, was this response tended to carry over to other things. For instance, I recall him saying it concerning the students shot at Kent State: “What did they expect?” We’d go ‘round and ‘round about that. “Maybe not to be shot down like dogs?” One point he liked to make in discussions I had with him about moral questions concerning World War Two was a powerful rejoinder I could never dispute:

“You kids know how it ended. We didn’t.”

BACK TO THE 21ST CENTURY

Let’s consider the 2020 leadership issue on board the aircraft carrier Theodore Roosevelt in the light of these WWII Navy movies. The story of the Theodore Roosevelt represents no less a human drama with lessons on leadership than the two classic WWII dramas mentioned above. In fact, it’s not hard to imagine Captain Brett Crozier as the protagonist of a future Navy film full of conflict, courage, cowardice and moral ambiguity — even comedy and tragedy. My choice to write and direct such a film would be Adam McCay, director of the caustically funny and entertaining Dick Cheney tragicomedy, Vice. Obtaining Navy support for such a film from today’s Navy leadership– the use of one of their aircraft carriers! — would be a bit of a challenge. But can we now CGI aircraft carriers?

It was Theodore Roosevelt who famously encouraged Americans to not be afraid to enter “the arena” of their time. When his crew’s well being was at stake, Captain Crozier was not afraid to enter the arena. He did not cower in fear of ambitious, heartless leaders. He acted at the time in what he felt was the best way he could for his crew. As the good skipper humbly pointed out the United States is not at war; it’s not necessary to keep steaming full speed ahead as you slide your dead off the fantail. He had the courage to decide he wasn’t going to sacrifice any more of his crew to belligerently show the flag in the South China Sea.

The Vietnamese presence in the drama of the Theodore Roosevelt naturally recalls the cruel and devastating 30-year war the United States unleashed on the peasant nation of Vietnam with, among other first-world tools of mechanized death, aircraft carriers anchored off the coast of Vietnam loaded with bombs and supersonic delivery systems driven by men like our national hero John McCain.

[Dancers welcome the carrier crew to Da Nang; Admiral John Aquilino laughs with kids at a charity center, and sailors play games with kids and Vietnamese military personnel. The Chinese are, no doubt, watching.]

The Vietnam War, of course, was rooted in a terrible leadership decision made by President Harry Truman in 1945. He sided with the French who, after defeat in Europe at the hands of the Germans and after being humiliated and de-fanged by the Japanese in Vietnam, wanted to return to Vietnam. We can never know, but some argue Roosevelt would have given the Vietnamese their liberty. Ho Chi Minh’s guerrillas were our friend and ally during WWII, but the French threatened they’d withhold support for the US Cold War with the Soviets if they weren’t allowed to re-colonize Vietnam. In retrospect, Truman’s was a terrible decision that ended up killing millions of Vietnamese and 58,000 Americans, as it sullied the US in the eyes of the world and threatened US stability at home.

The Vietnamese showed the world they’re resilient, very smart and don’t care to hold grudges with the United States. As they were in WWII — before Truman — they’re now our friends. Our aircraft carriers are invited to dock in Da Nang, and our sailors, like those rowdy sailors on “the bucket” in Mister Roberts, are allowed to go ashore to mingle with the amazing and beautiful Vietnamese people.

It seems Captain Crozier — who is certainly too diplomatic to say something like this — violated the ultimate US Military/Pentagon rule: Power trumps Humanity. This rule is why the issue of de-humanization is such an instrumental part of the struggle many of us who wore a US military uniform in places like Vietnam have chosen to undertake. The Theodore Roosevelt story is like ripe fruit crying out to be eaten. I see Captain Brett Crozier as a modern Mister Roberts in a story about leadership that actually gives a damn about those being led.

Navy leadership should be ashamed of itself.