A book review of:

MY LAI: VIETNAM, 1968, AND THE DESCENT INTO DARKNESS

By Howard Jones

Oxford: 2017

(This review first appeared in The Mekong Review, published in Leichhardt, Australia)

[Click here to go to Part Two]

Monsters exist, but they are too few in number to be truly dangerous. More dangerous are the common men, the functionaries ready to believe and to act without asking questions.

– Primo Levi

On 17 March 1968, the New York Times ran a brief front-page lead titled “G.I.’s, in Pincer Move, Kill 128 in a Daylong Battle”; the action took place the previous day, roughly thirteen kilometres from Quang Ngai City, a provincial capital in the northern coastal quadrant of South Vietnam. Heavy artillery and helicopter gunships had been “called in to pound the North Vietnamese soldiers”. By three in the afternoon, the battle had ceased, and “the remaining North Vietnamese had slipped out and fled”. The US side lost only two killed and several wounded. The article, datelined Saigon, had no byline. Its source was an American military command’s communiqué, a virtual press release hurried into print and unfiltered by additional digging.

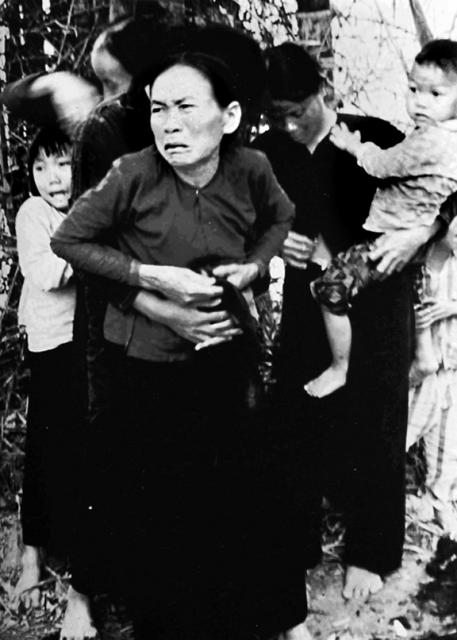

My Lai residents moments before being shot (Ron Haberle/WikiCommons)

My Lai residents moments before being shot (Ron Haberle/WikiCommons)

Several days later, a more superficially factual telling of this seemingly crushing blow to the enemy was featured in Southern Cross, the weekly newsletter of the 23rd Infantry (or Americal) Division, in whose “area of operation” the “daylong battle” had been fought. It was described by Army reporter Jay Roberts, who had been there, as “an attack on a Vietcong stronghold”, not an encounter with North Vietnamese regulars, as the Times had misconstrued it. However, Roberts’s article tallied the same high number of enemy dead. When leaned on by Lieutenant Colonel Frank Barker, who commanded the operation, to downplay the lopsided outcome, Roberts complied, noting blandly that “the assault went off like clockwork”. But certain after-action particulars could not be fudged. Roberts was obliged to report that the GIs recovered only “three [enemy] weapons”, a paradox that warranted clarification. None was given. It was to be assumed either that the enemy was poorly armed or that he had removed the weapons of his fallen comrades — leaving their bodies to be counted — when he retired from the field. Neither of the news outlets cited here, nor Stars and Stripes, the semi-official newspaper of the US armed forces, which ran with Roberts’s account, makes reference to any civilian casualties.

It would be nearly eighteen months later when, on 6 September 1969, a front-page article in the Ledger-Enquirer in Columbus, Georgia, reported that the military prosecutor at nearby Fort Benning — home of the US Army Infantry — was investigating charges against a junior officer, Lieutenant William L. Calley, of “multiple murders” of civilians during “an operation at a place called Pinkville”, GI patois for the colour denoting human-made features on their topographical maps of a string of coastal hamlets near Quang Ngai.

With the story now leaked, if only in the regional papers — it would migrate as well to a daily in Montgomery, Alabama — the Fort Benning public information officer moved to “keep the Calley story low-profile” and “released a brief statement that the New York Times ran deep inside its September 7, 1969 issue”, limited to three terse paragraphs on a page cluttered with retail advertising. The press announcement from the Army flack had referred only to “the deaths of more than one civilian”. In the nation’s newspaper of record, which also mentioned Calley by name, this delicate ambiguity was multiplied to “an unspecified number of civilians”. Yet, once again, the Times had been enlisted to serve the agenda of a military publicist and failed to approach the story independently.

An Army recon commando named Ron Ridenhour had taken it upon himself to investigate. While still serving with the Americal Division’s 11th Light Infantry Brigade, from which Task Force Barker — named for its commander — was assembled for the attack on Pinkville, Ridenhour documented accounts of those who had witnessed or participated in the mass killing. A year later, in March 1969, now stateside and a civilian, Ridenhour sent “a five page registered letter” summarising his findings to President Richard Nixon, the Joint Chiefs of Staff and select members of the US Congress, urging “a widespread and public investigation”. General William Westmoreland, who had commanded US forces in Vietnam until June 1968, reacted to Ridenhour’s allegations with “disbelief”. The accusations were, he told a congressional committee, “so out of character for American forces in Vietnam that I was quite skeptical”. Nonetheless, an inquiry was launched.

The Times, although forewarned, had once again squandered a chance to scoop for its readers what was arguably the most sensational news story of the entire Vietnam War. The two regional reporters had done their legwork, then, bereft of big-city resources, had nowhere else to go. But in late October, a seasoned freelance journalist in Washington named Seymour Hersh, acting on a colleague’s anonymous tip from inside the military, immediately “stopped all other work and began to chase down the story”, which by mid-November 1969 would be revealed to the American public and the world at large as the My Lai massacre.

This outline of the massacre’s initial falsification and suppression, followed by its eventual disclosure, is cobbled from My Lai: Vietnam, 1968, and the Descent into Darkness, a thorough retreatment of the atrocity by Howard Jones, a professor of history at the University of Alabama. The question is, to what end? Has the voluminous, careful study in the literature devoted to the My Lai massacre left something out? It’s not a matter of omissions, the historian argues, but that the record is replete with conflicting interpretations. To tell the “full story” required Jones to reorder events in their “proper sequence”, he says. His other reasons for taking us back to Pinkville are equally vague and casually embedded among several floating asides in the author’s acknowledgments. Jones’s debts are many, but foremost among them is the one to his Vietnamese-American graduate assistant, who “emphasized the importance of incorporating the Vietnamese side into the narrative and remaining objective in telling the story”.

I took this profession of objectivity as a signal to watch for its potential subjective or editorial opposite. Jones insists that “everyone who has written … about My Lai has had an agenda”. The suspicion that a subtle revisionist agenda, nurtured perhaps by the resentments of a partisan of the losing side (his assistant), might underlie Jones’s intentions for revisiting this much examined massacre was heightened by his anecdote about his wife’s emotionally fraught response to his grim descriptions of the slaughter. However revolting, the atrocities must be detailed, she insists. To do otherwise, the author agrees, “would leave the mistaken impression that nothing extraordinary took place at My Lai”.

That My Lai was extraordinary I hold beyond dispute. But the privileged attention given to the massacre by historians and other commentators — not to mention its impact on the general public, which by far prefers vivid superlatives to cloudy comparisons — hangs like a curtain across the broader and far grizzlier picture of the US-driven horrors of the Vietnam War that were commonplace. Would the historian tell that story, too, I wondered, as I plunged into his text? Or was the only purpose of taking up this subject again five decades on to ensure that the censorious curtain remained firmly in place?

Quang Ngai was a hotbed of resistance under the Viet Minh independence movement during French colonial rule. With the transition to the American War, resistance fighters — now reconstituted as the National Liberation Front, called the Viet Cong by its opponents — remained capable of striking at will throughout the province, which, until 1967, was under the jurisdiction of the South Vietnamese Army. But the US command found its native allies unreliable, without ever asking if perhaps their reluctance to challenge the local resistance rested not on fear or cowardice but on familiarity or even kinship. US soldiers possessed no such scruples.

After “intelligence sources” targeted the area around My Lai as “an enemy bastion for mounting attacks” on Quang Ngai City and its surroundings, US forces were concentrated under Task Force Barker, “a contingent of five hundred soldiers” set to bring the troublesome province under control of the government of South Vietnam.1

On the evening before the assault, Captain Ernest Medina — like Calley a principal target of the Army’s subsequent investigation — briefed the hundred men of Charlie Company under his command. “We are going to Pinkville tomorrow … after the 48th Battalion,” he told them. “The landing zone will be hot. And they outnumber us two to one … expect heavy casualties.” Charlie Company had already taken “heavy casualties” in the two months they’d been humping the boonies of Quang Ngai. The local guerrilla unit, the lethal, elusive 48th, was all the more feared because the GIs had never seen the face of a single combatant behind the sniper bullets or booby traps that bloodied and killed their comrades. “By the last week of February,” Howard Jones reckons, “resentment and hostility had spread among the GIs, aimed primarily at the villagers.”

Pinkville had been declared a free-fire zone. The mission for the assault was to search and destroy. If the soldiers encountered non-combatant villagers, the textbook regulations dictated that they be detained and interrogated as to the whereabouts of the enemy and then moved to safety in the rear. But the various strands of intelligence-gathering that guided Task Force Barker were interpreted to suggest there would be no non-combatants, because the villagers had been warned to evacuate, or, given that the assault was on a Saturday, residents who had defied evacuation would be off to the market in Quang Ngai City. This was all intel double-talk. The true military objective was to ensure the residents had no village to return to, because the GIs were primed to slay all livestock, lay waste to every dwelling and defensive bunker, destroy the crops and foul the wells — that is, to make My Lai and its contiguous hamlets uninhabitable and thus untenable as bases to support the guerrillas.

Beginning just before 8 a.m. on 16 March, the three platoons of Charlie Company were airlifted to the fringes of the Vietnamese hamlets where they expected to encounter fierce enemy resistance. The hail of bullets from helicopter gunships that churned up the earth around them, aimed at suppressing potential enemy fire, created for many of these soldiers who had never experienced combat the impression that they’d been dropped in the midst of the “hot landing zone” Captain Medina had promised them. But as Army photographer Ron Haeberle, assigned to document the assault, would later testify, there was “no hostile fire”. The headquarters of the 48th, and what remained of its fighters, had moved west in the mountains after being decimated during the Tet Offensive a month before. And the few Viet Cong who had been visiting their families around My Lai, hardly ignorant of US movements, had got out by dawn on the 16th.

Confused as to exactly what they were facing, Charlie Company’s platoons stepped off from opposing positions to sweep through the village, which was already partially damaged by artillery, intending to squeeze the enemy between them. Instead they soon confronted not the guerrilla fighters they were sent to dislodge but scores of inhabitants who weren’t supposed to be there. GIs immediately shot several villagers who had panicked and attempted to flee. In this war such trigger-happy killings were not far from the norm. But Lieutenant Calley “had interpreted Medina’s briefing to mean that they were to kill everyone in the village … Since it was impossible to distinguish between friend and foe, the only conclusion was to presume all Vietnamese were Viet Cong and to kill them all”. Calley, moreover, was being relentlessly spurred by Medina over the radio to quicken the pace of the First Platoon’s forward sweep, and therefore would later claim that he could neither evacuate the non-combatants nor, for reasons of security, leave them to his rear.

Jones offers from the record a facsimile of the field-radio transmission between Calley and his commander:

“What are you doing now?” Medina asked.

“I’m getting ready to go.”

‘“Now damn it! I told you: Get your men in position now! …”

“And these people, they aren’t moving too swiftly.”

“I don’t want that crap. Now damn it, waste all those goddamn people! And get in the damn position!”

“Roger!”

The idea of questioning orders, comments Jones dryly, never crossed Calley’s mind, particularly during combat.

One brief panel of the horror show will suffice to direct the imagination towards grasping what Jones styles a “descent into darkness”, which, given the scale of the ensuing carnage that morning, has elevated the My Lai massacre to the extraordinary status in the Vietnam War that history has bestowed upon it.

Calley, in the grip of all his embedded demons — his mental and moral mediocrity; his cracker-barrel, knee-jerk racism; his incompetence as a leader; his slavish kowtowing to authority (which clearly disgusted his commander and his troops); everything that conspired to create the monster he was — returned from his latest whipping by Medina to where a group of villagers sat on the ground, and demanded of two members of his platoon, “How come you ain’t killed them yet?” The men explained they understood only that they were to guard them. “No,” Calley said, “I want them dead … When I say fire … fire at them.” Calley and Paul Meadlo — whose name would became almost as closely associated with the massacre as Calley’s — “a bare ten feet from their terrified targets … [set] their M-16s on automatic … and sprayed clip after clip of deadly fire into their screaming and defenseless victims … At this point, a few children who had somehow escaped the torrent of gunfire struggled to their feet … Calley methodically picked off the children one by one”. “He looks like he’s enjoying it,” remarked one soldier, who, moments before, had been prevented by Calley from forcing a young woman’s face into his crotch but who now refused to shoot.

The mass killing, which Howard Jones parades scene by scene with exhaustive precision, continued throughout the morning until the bodies of hundreds of villagers lay scattered across the landscape: not just those killed by Calley’s platoon but those killed by others throughout the rest of Charlie Company — and not only at My Lai 4 but also at My Khe 4, several kilometres distant, by members of Bravo Company. “In not a few cases, women and girls were raped before they were killed.” Jones dutifully chronicles the accounts of the few who resolutely refused to shoot, and of one man who blasted his own foot with a .45 to escape the depravity. “Everyone except a few of us was shooting,” Private First Class Dennis Bunning of the Second Platoon would later testify.

But there was another man that morning who didn’t just seek to avoid the killing; he attempted to stop it.

Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson piloted his observation helicopter, a three-seater with a machine-gunner on each flank, several hundred feet above My Lai. Thompson’s mission was to fly low and mark with smoke grenades any source of enemy fire, which would prompt the helicopter gunships tiered above him — known as Sharks — to swoop down and dispense their massive firepower on the target. Spotting a large number of civilian bodies in a ditch, Thompson at first suspected they’d been killed by the incoming artillery. Hovering near the ground for a closer look, Thompson and his crew (Gary Andreotta and Larry Colburn) were stunned to witness Captain Medina shoot a wounded woman who was lying at his feet. Banking closer to the ditch, Thompson “estimated he saw 150 dead and dying Vietnamese babies, women and children and old men … and watched in disbelief as soldiers shot survivors trying to crawl out”.

Against regulations, Thompson landed and confronted Lieutenant Calley, asking him to help the wounded and radio for their evacuation. Calley made it clear he resented the pilot’s interference and would do no such thing. Thompson stormed away furiously, warning Calley “he hadn’t heard the last of this”. With Medina again at his heels, Calley ordered his sergeant “to finish off the wounded”, and just as Thompson was taking off, the killing resumed.

Aloft again, Thompson saw “a small group … of women and children scurrying toward a bunker just outside My Lai 4 … and about ten soldiers in pursuit” and felt “compelled … to take immediate action”. He again put his craft down, jumping out between the civilians and the oncoming members of the Second Platoon led by Lieutenant Stephen Brooks. When Thompson asked Brooks to help evacuate the Vietnamese from the bunker, Brooks told him he would do so with a grenade. The two men screamed at each other. Like Calley, Brooks was unyielding, and Thompson warned his two gunners, now standing outside the chopper, to prepare for a confrontation: “I’m going to go over to the bunker myself and get these people out. If [the soldiers] fire on these people or fire on me while I’m doing that, shoot ’em.”

That moment has been cast in the My Lai literature as a classic armed standoff. But Thompson’s two gunners had not aimed their weapons at Brooks and his men, who stood fifty metres away — it was a bit of manufactured drama several chroniclers of that confrontation, among them Hersh, have chiseled into the record. Jones in this instance went beyond the dogged task of compilation. While researching his book, he had spent many hours with Larry Colburn and befriended him. It was Colburn who told Jones that he and Andreotta did not aim their weapons directly at the soldiers who faced them. They tried to stare them down, “while carefully pointing their weapons to the ground in case one of them accidentally went off”. This verisimilitude restores a dimension of realism to a scene imagined by those who had never been soldiers.

Checking Brooks, but failing to get his cooperation, Thompson took another extraordinary step. He radioed Warrant Officer Danny Millians, one of the pilots of the gunships, and convinced him also to defy the protocols against landing in a free-fire zone. Then, in two trips, Millians used the Shark to transport the nine rescued Vietnamese, including five children, to safety. Making one final pass over the ditch where he’d locked horns with Calley, Thompson “hovered low … searching for signs of life while flinching at the sight of headless children”. Thompson landed a third time, remaining at the controls. He watched as Colburn, from the side of the ditch, grabbed hold of a boy whom Andreotta, blood spilling from his boots, had pulled from among a pile of corpses. Do Hoa, eight years old, had survived.

Livid and in great distress at what he had witnessed, Thompson, on returning to base, and in the company of the two gunship pilots, made his superior, Major Frederic Watke, immediately aware of “the mass murder going on out there”. From that moment, every step taken to probe and verify “the substance of Thompson’s charges almost instantly came into dispute”. Although Watke would later tell investigators he believed Thompson was “over-portraying” the killings owing to his “limited combat experience”, the major had realised that the mere charge of war crimes obliged him “to seek an impartial inquiry at the highest level”. The Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) required that field commanders investigate “all known, suspected or alleged war crimes or atrocities … Failure to [do so] was a punishable offense”. Having reported Thompson’s allegations to taskforce commander Barker, Watke had fulfilled this duty. But there was a Catch-22 permitting command authority to ignore the MACV directive if they “thought” a war crime had not been committed.

The trick here was for Barker and several other ranking officers in the division and brigade chain of command to assess whether civilians had been killed during the assault, and if so, how many. Captain Medina — in addition to contributing to the fictional enemy body count — would supply a figure of “30 civilians killed by artillery”. The division chaplain would characterize these deaths as “tragic … an operational mistake … in a combat operation”. For this line of argument to carry, however, it was necessary for the commander of the Americal Division, Major General Samuel Koster, the “field commander” who alone possessed the authority to prevent the accusations from going higher, to put his own head deep into the sand.

When Colonel Oran Henderson, who commanded the 11th Infantry Brigade, from which Medina’s Charlie Company had been detailed to the taskforce, ordered Lieutenant Colonel Barker in the late afternoon of 16 March to send Charlie Company back to My Lai 4 to “make a detailed report of the number of men, women and children killed and how they died, along with another search for weapons … Medina strongly objected”. It would be too dangerous, he said, to move his men “in the dark through a heavily mined and booby-trapped area … where the Vietcong could launch a surprise attack”. Monitoring the transmission between Barker and Medina, General Koster countermanded Henderson’s order. Later claiming he was “concerned for the safety of the troops”, Koster saw “no reason to go look at that mess”. Medina’s estimate of the number of civilian deaths, Koster ruled, was “about right”.

Not only had Koster’s snap judgment given Barker license to cook up the initial battlefield fantasy of 128 enemy dead; it also ensured that the internal investigations into the charges of “mass murder”, notably by Henderson and other high-ranking members of Koster’s staff, would not deviate from the conclusion voiced by the division commander. By navigating each twisting curve along a well-camouflaged path towards the fictive end those in command were seeking, Jones lays bare a virtual textbook case of conspiracy, which must be read in its entirety to capture the intricate web of fabrication and self-deception the conspirators constructed to assure themselves the crypt of the cover-up had been sealed.

When discussing the massacre later at an inquiry, the Americal Division chaplain, faithful to the Army but not to his higher calling, claimed that, had a massacre been common knowledge, it would have come out. That the massacre was “common knowledge” to the Vietnamese throughout Quang Ngai province on both sides of the conflict (not to mention among their respective leaderships on up to Hanoi and Saigon) goes without saying. Indeed, low-ranking local South Vietnamese officials attempted to stir public outrage about the massacre (not to mention negotiate the urgent remedy of compensation for the victims) but were suppressed by the Quang Ngai province chief, a creature of the Saigon government who fed at the trough of US matériel and did not wish to risk the goodwill of his US sponsors. My Lai was quickly recast as communist propaganda, pure and simple.

While this proved a viable method of suppression for South Vietnamese authorities, it could not still tales of the massacre in the scuttlebutt of the soldiers who had been there, who had carried it out. From motives said to be high-minded, but not fuelled by an anti-military agenda, and in the piecemeal fact-gathering manner typical of any investigation, the whistleblower Ron Ridenhour had thus resurrected the buried massacre and bestowed on Hersh the journalistic coup of a lifetime.

As the articles and newscasts about what took place at My Lai were cascaded before the public in November 1969, efforts to manage the political fallout by various levels of government were accelerated with corresponding intensity. Pushing back at the centre of that storm were Richard Nixon and other members of the executive; congressional committees in both the House and the Senate; and, not least, and in some cases with considerably more integrity than their civilian political masters, members of the professional military.

Not surprisingly, if one understands anything about US society, a substantial portion of the public, in fact its majority, expressed far greater sympathy for William Calley than for his victims. One could cite endemic US racism as a contributing factor for this unseemly lack of human decency. More broadly speaking, an explanation less charged by aggression would point to a level of provincialism that apparently can afflict only a nation as relatively pampered as my own. In such an arrangement, turning a blind eye for expedience’s sake towards the pursuit of global power, consequences be damned, is as good as a national pastime.

Despite the spontaneous public sympathy for Calley, Nixon fretted that news of My Lai would strengthen the anti-war movement and “increase the opposition to America’s involvement in Vietnam”. Nixon, true to form, lashed out with venom at the otherness of his liberal enemies. “It’s those dirty rotten Jews from New York who are behind it,” Nixon ranted, learning that Hersh’s investigation had been subsidised by the Edgar B. Stern Family Fund, “clearly left-wing and anti-Administration”. Nixon was strongly pressed to “attack those who attacked him … by dirty tricks … discredit one witness [Thompson] and highlight the atrocities committed by the Viet Cong”. Only Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird seemed to grasp that manipulation of public opinion would not perfume the stink of My Lai. The public might tolerate “a little of this,” Laird mused, “but you shouldn’t kill that many.” There was apprehension in the White House because calls for a civilian commission had begun to escalate. Unbeknown to his secretary of defense, Nixon, who was habituated to work the dark side, formed a secret taskforce “that would seek to sabotage the investigative process by undermining the credibility of all those making massacre charges”.

Nixon found a staunch ally for this strategy in Mendel Rivers, the hawkish Mississippi Democrat who chaired the House Armed Services Committee. As evidence from the military’s internal inquiries mounted to prove the contrary, members of Rivers’s committee sought to establish that no massacre had occurred and that the only legitimate targets of interest were Hugh Thompson and Larry Colburn (Gary Andreotta having been killed in an air crash soon after the massacre), who were pilloried at a closed hearing, virtually accused of treason for turning their guns on fellow Americans.

During a televised news conference on 8 December — with Calley’s court martial having already been under way for three weeks — Nixon announced that he had rejected calls for an independent commission to investigate what he now admitted for the first time “appears to have been a massacre”. The president would rely instead on the military’s judicial process to bring “this incident completely before the public”. The message the administration and its pro-war allies would thenceforth shovel into the media mainstream wherever the topic was raised was that My Lai was “an isolated incident” and by no means a reflection of our “national policy” in Vietnam.

As manoeuvres to reconsign the massacre to oblivion faltered, the Army was just then launching a commission of its own under a three-star general, William Peers, whose initial charge was to disentangle the elaborate cover-up within the Americal Division that had kept the massacre from exposure for almost two years. In order to reconcile the divergent testimonies among its witnesses, the scope of the Peers Commission soon necessarily expanded to gather a complete picture of the event the cover-up sought to erase. The Army’s probe, by its Criminal Investigation Command, on which charges could be based, and which would guide any eventual legal proceedings, continued on a separate track and beyond the public eye as a matter of due process.

After Lieutenant General Peers had submitted the commission’s preliminary report, Secretary of the Army Stanley Resor moved to soften the “abrupt and brutal” language. He requested that Peers refer to the victims not as “elderly men, women, children and babies” but as “noncombatant casualties”. And might Peers “also be less graphic in describing the rapes”? Resor, further, cut the word “massacre” from the report and, when presenting it to the press, had the chair of his commission describe My Lai rather as “a tragedy of major proportions”. Peers was reportedly indignant, but complied. It required no such compulsion to ensure that Peers toe the line on a far more central theme. Responding to questions from the media, Peers insisted there had been no cover-up at higher levels of command beyond the Americal Division and echoed his commander in chief’s mantra that My Lai was an isolated incident. When Peers was questioned about what took place at My Khe that same day, he insisted it was inseparable from what occurred at My Lai. No reporter challenged that assertion.

Investigators had a long list of suspects deployed at My Lai and My Khe in Task Force Barker (as well as those throughout the Americal chain of command) whom they believed should be charged and tried. Some forty enlisted men were named, along with more than a dozen commissioned officers. Only six among them, two sergeants and four officers, would ultimately stand trial. There would be no opportunity to enlarge the scope of the massacre through the spectacle of a mass trial that would, moreover, conjure images of Nuremburg and Tokyo, where the US had dispensed harsh justice on its defeated enemies only two decades earlier. It was agreed by both Nixon and the Pentagon chiefs that defendants would be tried separately and at a spread of different Army bases.

If the elaborate subterfuge employed to cover up the massacre had been the work of individuals desperate to protect their professional military careers, the court-martial proceedings reveal how an entire institution operates to protect itself. Georges Clemenceau, French prime minister during the First World War, is credited with the droll observation that “military music is to music what military justice is to justice”. Jones, using the idiom of the historian, demonstrates in his summaries of the trials the disturbing reality behind Clemenceau’s quip.

[Click here to go to Part Two]