Stephen Paddock, the 64-year-old reclusive multi-millionaire who spent much of his “mysterious” later adult life in one-on-one relationships with casino poker machines, is everywhere labeled an “enigma.” That’s the consensus from every quarter. New York Times reporters put together a sketch of who this guy was.

“Stephen Paddock was a contradiction: a gambler who took no chances. A man with houses everywhere who did not really live in any of them. Someone who liked the high life of casinos but drove a nondescript minivan and dressed casually, even sloppily, in flip-flops and sweatsuits. He did not use Facebook or Twitter, but spent the past 25 years staring at screens of video poker machines.”

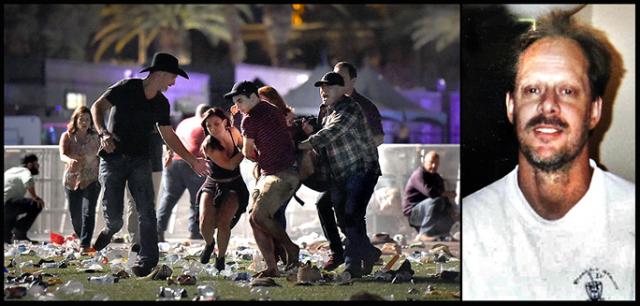

Civilian first responders carrying a wounded victim, and the killer, Stephen Paddock

Civilian first responders carrying a wounded victim, and the killer, Stephen Paddock

He had a house in Sun City, Mesquite, one of a number of Del Webb gated, “active adult communities,” this one 90-minutes from Las Vegas. Plus, he owned other houses and properties; at one point he owned two airplanes and, to facilitate his lifestyle, bought cheap houses near local airports in Nevada and Texas where he parked his planes. He spent hours and hours as a “high-limit player” working the $100 poker machines in specially designed lounges for such cherished players, distinguishing them from the peasant riff-raff working the dollar machines. He was encouraged to continue gambling with free meals and free hotel rooms. “Gambling made him feel important,” the Times reporters wrote. He counted on the attentions of “high-limit hostesses” to get him food and refreshments and to fluff him up when his spirits lagged. He exhibited impatience if these hostesses were slow in delivering what he wanted. Other services were private matters.

Everything was done to cater to Stephen Paddock’s needs and whims — just keep him gambling. He became so close to one of the high-limit hostesses — Marilou Danley — she left her casino employment to be Paddock’s steady girlfriend, one of the few close human relationships he seems to have had. And it seems to have been a good relationship; he traveled with Danley to her home country in the Philippines for one of his birthdays and met her sisters. His brother Eric has only nice things to say of him; especially, that he was generous. His tenants all told the Times Paddock was fair and responded to all their needs. And, of course, he collected dozens of very expensive, very lethal weapons. In a social sense, he was a misfit and could be curt, but in the very American context of being smart enough to figure out how to exploit the real estate market and to accumulate money and property, he was a winner.

No one will speculate why Paddock did what he did. Glimmers of “why” do appear in the Times story in an indirect reference to “a law enforcement official” being told by his girlfriend, Marilou Danley (now an FBI “person of interest”), that “he seemed to be deteriorating in recent months both mentally and physically. … To the few people who knew him well, it is the only plausible explanation.” The problem is the FBI is a tight-lipped organization that shares with the public only the information that fits the legal narrative it’s pursuing and information that makes them look good. One thing that’s clear about the follow-up coverage of Paddock’s actions is that there is a narrative rule: “law-enforcement” and “first-responders” must be heroes in the tale. Also, as the political right emphasizes ad nauseum, “it’s too soon to get political about the story.” Too soon? Tell that to people like the President of the United States who Tweets on things like this before most of us get up in the morning. The fact is, as the great Leonard Cohen song goes, “everybody knows” the story is really about guns and the National Rifle Association.

Paddock established a dubious record for mass murder with an incredible collection of AR-15s modified to fire on full-automatic. Through two sealed windows broken with a hammer, he fired incessantly for over 11 minutes into panicked country music fans 32-stories below him. In a predictable follow-up, President Trump articulated the safe national consensus: Paddock’s behavior was “an act of pure evil” that was “sick” and “demented.” No argument there; it was a rare moment of consensus with the American people for a narcissistic president whose approval ratings are at 32 percent and dropping. All government and mainstream media sources demurred when it came to speculating what this man’s motive could have been for gunning down 58 and wounding almost 500 people. Some argued he should be declared a “terrorist,” which is one of the most abused and meaningless words in the English language. While there was a flaky rumor of an ISIS connection, the fact is, he wasn’t Muslim, so in the current climate of craziness in America he couldn’t be a terrorist. One website exhibited a photo of a man in a “pussy hat” at an anti-Trump rally, suggesting it was Paddock; that did not seem to get legs. Alex Jones predictably suggested it was a “false flag” operation.

So what was Stephen Paddock’s grievance?

I’m going to wade into this and go out on a limb (mixing metaphors along the way) to speculate that Mr. Paddock’s motivation for such an unspeakably “evil” act lurks in plain sight, in the details of a control-obsessed, soulless existence that festered under the protection of a cocoon of money in a culture fixated on money in a city known for selling fantasy. I have nothing against Las Vegas and have friends who like to go there to relax. That the sight of this outrage was Las Vegas, a city founded in the Nevada desert by gangsters and businessmen seeking profit from ordinary people’s fantasies and greed, should not be surprising. The city even markets itself as a unique and amoral place where anything goes: “What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas.”

The ad agency that came up with that slogan 10 years ago, wrote the following in support of the campaign:

“The emotional bond between Las Vegas and its customers was freedom. Freedom on two levels. Freedom to do things, see things, eat things, wear things, feel things. In short, the freedom to be someone we couldn’t be at home. And freedom from whatever we wanted to leave behind in our daily lives. Just thinking about Vegas made the bad stuff go away. At that point the strategy became clear. Speak to that need. Make an indelible connection between Las Vegas and the freedom we all crave.”

If you have the cash, Vegas will do its best to cater to whatever fantasy you desire. You can be a king or a queen in Vegas — or more accurately, as Dirty Harry famously put it, you can be “a legend in your own mind.” Without guilt. But, then, there’s a catch. You can indulge in all the fantasies you can afford until your cash runs out. Then, you become a loser and the city turns hostile. There’s nothing left for you. You slink away in shame to lick your wounds, preparing for another day. Las Vegas is a Valhalla of money and sex. A large, urban municipality devoted to transforming the so-called low-rent “combat zone” in American cities of yore into a post-sexual-revolution, family-friendly, X-rated Disneyland.

The context: An Absurd Two Weeks:

Context is everything. As a 70-year-old, officially disenchanted American Vietnam veteran, the past two weeks leading up to this incredible public massacre have been especially absurd. It is my contention you can’t understand Stephen Paddock without understanding the mercenary absurdity of America 2017.

First, I joined many of my Vietnam veteran friends in watching every minute of the Ken Burns/Lynn Novick 18-hour PBS film on the history of the Vietnam War. While the film was politically balanced and focused on personal narrative, by the end of the 18 hours, the dishonesty, cruelty and even criminality of the Vietnam War was clear. It was not flogged, but it was there. We learned that as far back as 1962 John F. Kennedy knew the US war against the Vietnamese — set off in 1945 by a Cold War panicked President Truman — was a bust and un-winnable. The filmmakers dug up a quote from JFK that went something like this: “I know this can only lead to failure. But if I withdraw I can’t be re-elected.” Gee! That kind of political self-serving, elite reality characterized the war until the bitter end 13 years later. It would be different if the US moral failure in Vietnam had resulted in few casualties. That it involved over a decade of relentless, mechanized slaughter on an unprecedented industrial scale directed against a peasant culture that had done absolutely nothing against the United States turned it into a tremendous moral crime. B52s versus water buffaloes. That Ho Chi Minh and his Viet Minh had been our friend and ally against the Japanese during WWII added insult to injury and made the war an incredible betrayal. The Vietnam War was a case of rot starting at the head and spreading down into the culture. And that rot still exists in the National Security State. Needless to say, the extent of killing our leaders unleashed against the Vietnamese people makes Mr. Paddock’s “lone wolf” act picayune by comparison.

Next, there was Harvey, Irma and Maria. Global warming was hardly mentioned. Maria devastated a Caribbean island that’s essentially an American colony. Puerto Ricans are citizens of the United States — but they can’t vote and aren’t quite full-fledged “Americans.” President Trump reminded the mayor of San Juan of this in Tweets. He alluded to Puerto Rico’s debt issues, suggesting maybe the island shouldn’t be so pushy asking for help. The implication was, they’re “losers,” and they should be grateful for what they get from the United States of America. As George W. Bush congratulated his FEMA director during Katrina, Trump assured his bigoted base that FEMA and the US was doing a magnificent job in Puerto Rico. Wink. Wink. The dog whistle was clear: Puerto Ricans are no better than Mexicans. They need to know their place in the renewed, great America. The money is tight these days and exceptional Americans (USA! USA!) can’t afford to bail out a bankrupt island.

Then the former oil executive, now Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson called his boss a “moron” and refused to retract the charge. In private, President Trump went ballistic. Rex immediately called a huddle with his simpatico teammates, White House Chief of Staff John Kelly and Defense Secretary James Mattis. If only we could have been a fly on the wall for that meeting. In public, Trump was all smiles. He loved Rex Tillerson. Then, in one of the more scary moments in the Trump administration, in a large group shot of military personnel and their wives at a dinner, Trump responded to a question by saying, “This is the calm before the storm.” “What storm?” reporters asked. “You’ll find out.” This is a commander-in-chief with access to nuclear codes who has publicly poked the volatile Kim Jung Un with a stick; you had to wonder what he was capable of doing to distract from all the bad press piling up. Was it an off-the-cuff bluff threat — ie. bullshit? Or was he referring to something planned? Then you realized, this is how the man gets attention. You had to wonder, when does the insecure, empty bravado catch up with the man to the point he has to back up the bravado with real action?

Then came Las Vegas. As their accomplishments have only grown in horror, lone wolf gunmen have become a cliché in America circa 2017. Yet, this one was novel and particularly worrisome. Here was a narcissistic, lone wolf multi-millionaire with no paper trail who was able to clock up a record number of murders. In an age of i-phone addiction, the only way to sum up the event was with a cyber imogee derived from Edvard Munch’s “The Scream.” The horror! The horror!

For me, Stephen Paddock’s 32nd floor rampage brought to mind Charles Whitman in 1966 atop a tower in Texas. Also, it felt like a 2017 version of Jimmy Cagney’s famous “Top o’ the world, Ma!” last act in White Heat. If the jig is up, go out with a bang! If girlfriend Danley’s allusion to deterioration is correct, things must have been closing in on 64-year-old Stephen Paddock. He was getting old, something I can attest affects one’s sense of self and the realities of one’s power. You face that reality with grace — or you don’t. As some great philosopher put it, we understand life backwards but are doomed to live it forward. Despite all the protective money, his loner, control-fixated lifestyle may have become harder and harder to sustain. His absent, bank-robber father was described as a “psychopath” who made the FBI’s most wanted list, a dangerous man who was said to be good at escape and evasion. Paddock liked to keep moving among his houses and apartments and hotel rooms. He avoided real poker games with real human beings where social skills and the art of bluffing counted. Instead, he played for periods up to 14-hours one-on-one with machines.

Was Stephen Paddock mentally ill? To me, it’s a moot point in the age we live in. One, psychopathy doesn’t seem to be a “mental illness” so much as a human characteristic, having a mind that works without a conscience like the mind of a predatory tiger. And, two, with money, the vicissitudes of mental illness are easier to manage and conceal. A “safe place” is a commodity to be purchased, especially if one can move around freely place to place, keeping ahead of one’s social challenges. Stephen Paddock was an individual who understood what the existentialist Jean Paul Sartre meant when he famously said of his one-act play No Exit: “Hell is other people.”

Imagination As a Tool That Cuts Through Fog:

We live in an outrageously complex hi-tech world of such governmental and corporate secrecy, such incredible amounts of self-serving dishonesty and bullshit, that I wonder whether the only way to really see through the secrecy and bullshit — the only way to really grasp the desperate, complex world we live in — is to assume an essentially arrogant strategy of projecting the imagination into what has become the fog of life. For me, it’s a hybrid form of fiction and non-fiction. Facts are no longer potent when a charge of “fake news” can emasculate a story. In 1973, Norman Mailer coined the term factoid. In books like Armies Of The Night, he worked in the hybrid genre of “new journalism.” He’s the same literary trickster who ran for mayor of New York, sometimes drunk, under the campaign of “Cut the bullshit!” Truth is a shifting thing, for sure, but it’s still a transactional possibility, especially in the realm of literature and art. It doesn’t rely on facts or even reality; it involves the responsible imagination and things like pattern recognition and narrative. You trust such a writer or you don’t. Here’s the Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa upon winning the Nobel Prize in 2010:

“Literature creates a fraternity within human diversity and eclipses the frontiers erected among men and women by ignorance, ideologies, religions, languages, and stupidity.” He talks of literature in oppressive regimes and wonders “why all regimes determined to control the behavior of citizens from cradle to grave fear it so much they establish systems of censorship.” The answer is simple: “[T]hey know the risk of allowing the imagination to wander free.”

Consider the poet/rock star Patti Smith, an artist in full synch with Vargas Llosa’s thinking.

“What is the task?” she wonders in a 2017 book called Devotion. “To compose a work that communicates on several levels, as in parable, devoid of the strain of cleverness. What is the dream? To write something fine, that would be better than I am, and that would justify my trials and indiscretions. … Why do we write? … Because we can’t simply live.” Because we want to be part of the great conversation of our times.

All human beings (even animals) have inner lives that, at every moment, interplay with reality, especially all those “other people” out there. What we share with other people is what Friedrich Nietzsche called “the will to power.” That is, all human beings want to be free and to do what they want. In his 1984 book titled The Politics of Meaning: Power and Explanation in the Construction of Social Reality, Peter Sederberg sifts this down to what he sees as the fundamental equation of politics: the struggle over meaning.

“Politics consists of all deliberate efforts to control systems of shared meaning. … The existence of shared meaning is a social puzzle to be solved not by a philosophical determination of the meaning of an event but by comprehending how human beings establish mutuality in an inherently polysemantic world. … In this dialectical fashion we are both the creators and the products of shared meaning.” As Vargas Llosa notes, some people would discourage by any means available this kind of social dialectic.

The kind of politics Sederberg speaks to may be a lost art these days. For it to work right demands respectful exchange. It’s a social enterprise requiring human interaction, which can seem the antithesis of political life in the age of the internet. In Sederberg’s view, violence can and does tilt the scales in the political struggle for shared meanings. Complexity poses a major challenge, as does the internet. “As a society grows more complex,” he writes, “the problem of generating and maintaining shared meaning also becomes demanding.”

In a book titled Voluntary Simplicity: Toward a Way of Life That Is Outwardly Simple, Inwardly Rich, Duane Elgin describes four stages of growth and decline for western industrial civilizations. There’s Growth Stages One and Two, and Decline Stages Three and Four. He concluded back in 1981, the beginning of the Reagan years, that the US was somewhere in Stage Three of Initial Decline. Thirty-six years later, at the beginning of the Trump regime, I’d conclude we’re in the early part of Stage Four, the Breakdown stage. Here’s some of how Elgin describes Stage Four Breakdown:

“This is the winter of growth for industrial civilization. It is an era of despair as all hope that things can return to their former status is exhausted. … Social and bureaucratic complexity has reached overwhelming levels. The society and its institutions are no longer comprehensible and are increasingly out of control. Social consensus and a shared sense of social purpose have all but vanished. … Leaders govern virtually without support. The regulatory apparatus … [is] unable to cope with the overwhelming complexity, the loss of social legitimacy. … The situation has become intolerable and untenable. The need for fundamental change is inescapable.”

Feel familiar? Add to Elgin’s list (he wrote before the internet) the incredible growth of secrecy and the rise of government surveillance of cell phones and computers that we only have a glimpse of, thanks to brave whistle-blowers and things like Wikileaks. Not to mention the issue of hacking. True privacy is a delusion and a joke; the best we can ask for is to be anonymous and deemed harmless. Frightening events like Stephen Paddock’s Las Vegas massacre only intensify the fear and paranoia and lead to further violations of civil and human rights and more obsession with guns. Am I being paranoid? The reclusive novelist Thomas Pynchon famously said: “Even paranoids have enemies.” Everything seems to contribute to the unraveling of the social glue holding things together, pushing us deeper into Stage Four Breakdown.