[Al Qaeda’s] strategic objective has always been … the overthrow of the House of Saud. In pursuing that regional goal, however, it has been drawn into a worldwide conflict with American power.

- John Gray, Al Qaeda and What It Means to Be Modern

Al Zarqawi … is an example of how the west has created bogeymen. Al Zarqawi is also an example of how the bogeymen have a habit of, eventually, fulfilling the role we give them.

- Jason Burke on the founder of al Qaeda in Iraq and, by extension after his death, ISIS

I know it’s not patriotic, but every time I hear some politico talk of bombing Iraq and Syria in response to the gruesome massacre in Paris I think of The Battle Of Algiers and the scene where a leader of the guerrilla movement is captured by the French military. A French reporter asks the man how he can justify the gruesome carnage from explosions in cafes and bars. “We’ll be glad to exchange our satchel charges for your jet bombers,” he says.

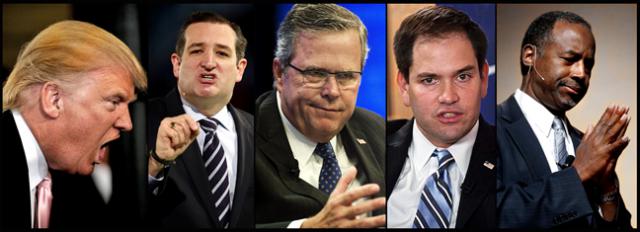

“Bomb the shit out of ISIS!”, screw civilian casualties, save Christians and one of the refugees might be a bad guy

“Bomb the shit out of ISIS!”, screw civilian casualties, save Christians and one of the refugees might be a bad guy

Always angling to be the farthest right of his fellow Republicans, candidate Ted Cruz honed in on the moral issue from Dick Cheney’s dark side. Cruz questioned whether a concern for civilian deaths was fitting when it came to the need to bomb ISIS in Iraq and Syria. Jeb! said we should only protect Christian refugees. Trump hollered to his fans, “We need to bomb the shit out of ISIS!” Rubio decried not having thorough dossiers on the refugees. The brilliant surgeon smiled beatifically. Pressed by the reactionary right of Marine Le Pen’s National Front, French President Hollande publicly declared war (whatever that meant in 2015) and increased the number of bombing raids on targets inside Syria provided by US intelligence. Reports suggested there were significant civilian casualties. Anti-Assad activists pleaded on Twitter for the French and other western forces to restrain their bombing, since, as Cruz understood, western bombs kill lots of people victimized by ISIS. Being caught in the crossfire between ISIS and the bomb-crazy West helps drive refugees to flee to Turkey and Europe. Sympathy for these refugees is evaporating rapidly, since fear-mongering demagogues are stigmatizing them as potential terrorists. Twenty US governors have said, “Not in my backyard. Send them back to where they came from.” MSNBC’s Chris Matthews got worked up into a lather and wanted all the able-bodied refugee males to return to Syria as a fighting force. Not a bully Teddy Roosevelt type, the Peace Corps veteran didn’t volunteer to lead it.

It’s not a pretty picture of western humanity in crisis. Narcissism is not a wholesome trait.

The West feels righteous in bombing; it doesn’t seem to know what else to do. Unlike “the terrorists” who attack innocent civilians in restaurants and music venues, the West proudly declares it does not intentionally target civilians. The scene from The Battle of Algiers suggests the truth is always complicated. In such a fear and vengeance heavy cycle, the question which side ends up snuffing out more “innocent” civilians is avoided as too intellectual, too much a trap leading into unpleasant discussions of history and morality. This was true following 9/11 and is now flowering again following Paris. Intense emotions of horror and mourning leading to calls for vengeance trump the understanding of history and the tiresome search for truth. It certainly trumps the cause of peace.

ISIS, a US bombing and refugees on the run — maybe comin’ to get yo’ mama

ISIS, a US bombing and refugees on the run — maybe comin’ to get yo’ mama

Like the scene from The Battle of Algiers, Paris and its aftermath calls to my mind a tragically prescient remark by Susan Sontag in the aftermath of 9/11. “By all means let’s mourn together, but let’s not be stupid together.” The consensus today is that the invasion/occupation of Iraq was a terrible foreign policy decision. It’s why George W. Bush is a virtual hermit. In retrospect, sacrificing thousands of American lives, hundreds of thousands of Iraqi lives and trillions in US resources to invade and occupy a nation that had nothing to do with 9/11 was a clear case of being “stupid together.” All it accomplished was to empower Iran and infuriate Sunni Arabs like Abu Mos’ab al Zarqawi in western Iraq to morph themselves into a psychopathic regime they call The Islamic State. Those determined to see it otherwise are, in Sontag’s equation, being willfully stupid for their own ends, which usually means they want to look tough.

Though the United States, Britain and others bear significant responsibility, the Islamic State is a regional problem. I’m not a pacifist, and I’m not suggesting a murderous regime like ISIS can be de-fanged and displaced from power without violence. The best example is the murderous Khymer Rouge regime in Cambodia, also a reaction to US provocation. That regime was made history by the Vietnamese, once they’d rid themselves of United States aggression. In the Middle East, Saudi Arabia is key, since its Wahhabism is the inspiration for al Qaeda and ISIS; it’s the Saudi’s decadent riches and pro-western politics that angers these extreme elements. The Saudis don’t want to touch this Pandora’s Box with a ten-foot-pole; the US knows that upsetting the decadent Saudi Kingdom by asking it to fight ISIS will only further empower Shiite Iran. Turkey, of course, has made a devil’s bargain with the US for an airbase: The proviso is the US will stand aside as Turkey attacks the Kurds, by far the most effective force fighting ISIS. The real problem in the Middle East is how royally screwed up it is. European colonialism and US imperialism had a great deal to do with this. It’s hardly surprising the Saudis, the Egyptians and the Israelis tragically depend on the American National Security State to save them from themselves. It’s not surprising that many of those left over — like Iran — hate us for the same reasons.

Instead of working to resolve this ever-more-compelling quagmire — ie., using our good offices to maturely figure out and help implement a sane, mutually-workable regional structure — most US leaders characterize the problem as the United States has lost its mojo as leader of the free world, and the only way to get it back is more violence. Richard Slotkin wrote a book in 1973 called Regeneration Through Violence: The Mythology of the American Frontier, 1600-1860. His thesis is that our “founding fathers” were really not those powdered-wig enlightenment sophisticates in Philadelphia who wrote the founding documents breaking away from Britain. No, our true founding fathers were “those who … tore violently a nation from the implacable and opulent wilderness.” They were rogues, adventurers, missionaries and killers. Slotkin’s thesis is “the myth of regeneration through violence became the structuring metaphor of the American experience.” When the going got tough, somebody was gonna die.

When this expansive, frontier mentality reached the Pacific Ocean, America was so full of itself the myth of regeneration through violence leaped to places like the Philippines and, in the 1960s, to Vietnam. Baghdad, Falluja and Mosul were late signposts in this mythic narrative of violence. Americans were disgusted with a corrupt Richard Nixon, so they tried something different and elected Jimmy Carter, a truly decent man who tried vainly to warn the nation there was a “malaise” at work in our culture. But implicitly understanding Slotkin’s message was Carter’s tragic flaw. America couldn’t handle the truth. Ronald Reagan, in turn, had a genius for understanding myth and symbol, and unlike Carter, he employed them as leverage for a classic regeneration movement.

“A people unaware of its myths is likely to continue living by them,” Slotkin writes.

Most of our current polarized political struggles are fought on this level; realism and history are anathema to most politicians. On the other hand, radicals on both sides — let’s call them the warmongers and the peacemongers — tend to understand this, since what radicals do is trace problems back to their roots. There’s the national obsession with guns and what they represent in the frontier myth of regeneration through violence; there’s the struggle centered on race that reaches back to the founding of this nation and the need to violently control African slaves, something loaded with mythic assumptions that continue to haunt us deep in our minds; the same with immigration and the impulse to keep newcomers out, something that was evident among my ancestors, part of a second wave of Puritans who were treated shabbily by the first wave, driving the newcomers to move west into Connecticut and beyond; this led to Manifest Destiny and the need to pacify and violently eliminate the native peoples who lived on the land and were inconvenient to the deeply-felt destiny of expropriation.

All this mythic baggage is culturally evident in old movies. It’s not until the volatile 1960s that things begin to shake up. There’s the Civil Rights Movement; there’s the movement questioning the Vietnam War and its incredible imperial cruelty rooted in European colonial control of Asians; there’s the sexual revolution and its political ramifications for women and homosexuals. There’s all the successes of Capitalism and the rise of technology, leading to the current state of globalization, which is rapidly putting the screws to the Nation State that began in Westphalia back in 1643. Money has lost all respect for borders. The backside of this is what we like to call terrorism. All the horrors of European Colonialism and American Imperialism come home to roost in a hi-tech world without borders. The subtitle of Abdel-Bari Atwan new book is right on-time: Islamic State: The Digital Caliphate. Like money, the subversive power of the internet and social media doesn’t respect national borders either.

A Columbia University political scientist of Indian descent born and raised in Uganda named Mahmood Mamdani understands this. He’s the author of Good Muslim, Bad Muslim: America, the Cold War and the Roots of Terror. He concludes the 2004 book this way:

“Just as America learned to distinguish between nationalism and Communism in Vietnam, so it will need to learn the difference between nationalism and terrorism in the post 9/11 world. To win the fight against terrorism requires accepting that the world has changed, that the old colonialism is no more and will not return, and that to occupy foreign places will be expensive, in lives and money. America cannot occupy the world. It has to learn to live in it.”

There are two ways to do this. One, as in Vietnam, we can follow the tired old Rudy Guilianis and the young, energetic Marco Rubios and pursue a very costly 21st century military conflagration in which all parties fall prey to a learning curve that begins with terrorist acts like Paris and a relentlessly vengeful imperial reaction. Decades hence, after a great many dead and much destruction, Mamdani’s lesson will become fact for those who survive. And people will write books — like they do about World War One — on how tragically stuck in the past world leadership was circa 2015.

John Gray, the political theorist at the London School of Economics quoted at the top, sees the fate of US imperialism this way:

“First, [Pax Americana] presupposes that the US has the economic strength to support the imperial role it entails. Second, it assumes that the US has the will to sustain it. Third, it requires that the rest of the world be ready to accept it. It is questionable whether any of these conditions can be met.”

The alternative to a new world war is to encourage listening to and talking with those we demonize as the enemy. I know, to anyone trapped inside the myth of regeneration through violence this is simple, naïve and silly. That’s a tragically short-sighted view. The warmongers (it’s a word we should resurrect) are the first to damn talking to anyone other than people just like themselves. This generally applies on the governmental level, among Wall Street fat cats, all the way down to the big-truck working-class heroes who love America so much. During World War One, they put Eugene Debs in jail for talking peace in what turned out to be a very bloody, unpopular war rooted in disastrous leadership all around. The most courageous and responsible elements of the peace movement are always marginalized — and if they don’t shut up, arrested and humiliated — for suggesting there are alternatives to the vengeful call to violence. Think of all those people who begged the George W. Bush administration not to invade Iraq. Tens of millions of people took to the streets of the world’s major cities; we had an unprecedented march the cops put at 10,000 people here in the streets of Philadelphia. Violence and militarism have now so pervaded our culture and inner lives that good-minded people are simply demoralized: There’s nothing to be done.

But alternatives to violence exist. There are many good, strong people in the world representing all sides and parties in today’s conflicts willing to sit down and talk, to listen and to dialogue. Since it’s a microcosm of the western war on terror, take the intractable case of Israel and Palestine. Would it be as intractable if for the past forty years there had been a well-supported dual track system: for lack of better terms, one operating as a vengeance track and another operating as a forgiveness track. We have the former in spades; it’s the latter that doesn’t exist or is grotesquely marginalized. The notion of vengeance is easy to grasp. Forgiveness is not, since it’s generally disparaged as condoning the acts of heinous killers. That’s the bad rap; forgiveness is actually about moving beyond the vengeance to establish workable structures for living in peace.

The point is to somehow empower some kind of peace-seeking track. Warmongers like to trash the United Nations for corruption, inefficiency and other shortcomings. What’s so preposterous about this is it assumes the alternative institutions of war and violence are pinnacles of virtue and efficiency. Failure is always a reality for anyone who has the temerity to act in this world. But the failure of the peace movement isn’t the peace movement’s fault; that failure is attributable to those who will allow no alternative to violence and, thus, perpetuate the cycle of violence.

Many beloved assumptions would have to be questioned. For instance, the New York Times characterized the attack in Paris as a “security breakdown.” That’s an assumption of western exceptionalism, a state-of-being in which peace and harmony are virtual rights of western culture. The Times, of course, meant that Paris was a “breakdown” of the powerful western surveillance system that’s assumed to know everything as it insinuates itself deeper and deeper into our privacy. In the next paragraph, the Times pointed out the Paris attackers showed “a growing and ominous sophistication among terrorist networks.” This assumes extremists are too stupid to follow a normal learning curve, that they are unable to extrapolate how our surveillance capabilities work and figure out how to run around them. Like maybe taking six months to plan employing bus travel and face-to-face meetings. With cell phones and email technology, they might have planned the operation in a week. These extremist elements have always said time was never an issue for them.

Every conclusion I’ve heard on the part of those with power points to more indiscriminate killing in lands far removed from the US and a greater curtailment of human rights within the US. So my conclusion is this: A plague on all the warmonger’s houses. I have no qualms about shooting terrorists down like dogs to save people’s lives; so this argument is not about being squeamish. What I’m sick of is the mutual escalation cycle.

All I want is an empowered track of well-funded peacemongers with institutional teeth. I’m sick and tired of a marginalized peace movement that’s disrespected and ridiculed for advocating smart things like not invading and occupying Iraq in 2003. There’s got to be a better way than escalating the current intractable mess into a world war to learn the lesson Mahmood Mandani says we Americans are doomed to learn: How to live in the world without ruling it.