Kill one person, it’s called murder.

Kill 100,000, it’s called foreign policy.

- A popular bumper sticker

Everybody seems angry and frustrated these days. What’s important is what people do with that anger and frustration. It’s also important to understand the roots of all this anger.

A black preacher who was part of the peaceful Black Lives Matter street protest in Dallas the night when five cops were killed told an MSNBC reporter after the killings he was still angry over the killings by police of black men in the last three days and in previous months. He carried a baseball bat over his shoulder. Likewise, in a separate but related realm, Iraqi exile Sami Ramadani confessed on Amy Goodman’s news program that being asked to comment on the recent Chilcot Report detailing the culpability of the British government for the Iraq War was difficult for him because of the incredible anger the subject incited in him.

These two men are not a problem. They were able to channel their anger into constructive paths, one a preacher/protester, the other a writer/commentator. I share the anger expressed by these men, as I share their devotion to peaceful modes of expression.

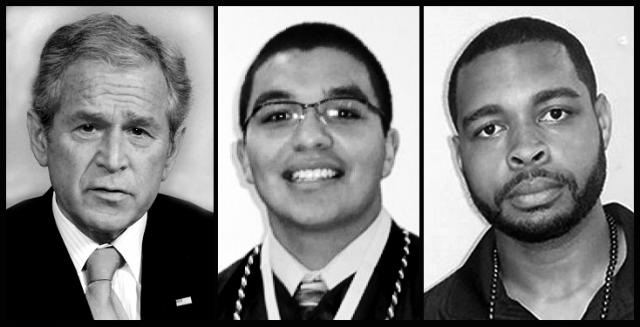

The problem we face in this nation comes from another quarter: It comes from those who, for one reason or another, feel compelled to address their frustrations, fears and sense of insulted self-image by using violence. This category involves people of all classes and levels of status. I would put former President George W. Bush and others like him in this category of resorting rashly to senseless violence. The category would also include Jeronimo Yanez, the cop who shot Philando Castile in St. Paul, and Micah Johnson, the military veteran who murdered five cops in Dallas.

Three killers: George W. Bush, Jeronimo Yanez and Micah Johnson

Three killers: George W. Bush, Jeronimo Yanez and Micah Johnson

I think I hear someone crying “foul!” Let me explain. First, I include the former president in such a category to make a larger point about the state of America circa 2016. I’m a realist, so I don’t expect Mr. Bush will be arrested anytime soon. The point is to actually think about what it means to kill people and to mourn for loved ones. The killings in Dallas were heart-wrenching; on the media, there were endless references to the mourning families of the killed officers. Again, heart-breaking and infuriating to ponder. But what angers me most is the mourning relatives of undeserving African Americans killed by cops and the hundreds of thousands of relatives of the dead in Iraq whose on-going grief should be on the conscience of George W. Bush and “killers” like Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld and Colin Powell. The dead in Iraq never seem to get much attention, and the crimes of the ruling class seem to just slip away into some obscure memory hole. The Iraq War opened up a Pandora’s Box and let out a host of horrors. ISIS is one of these horrors. Another is a deepening distrust of government. Official forgetting is epidemic.

On MSNBC, Fox and CNN, I listened to one self-righteous TV talking head after another wring their hands in disbelief over Micah Johnson’s shooting of Dallas cops. I think it was a woman on Fox who said: “I can’t understand why someone would do a thing like this.” Is this woman mentally deficient? I don’t think so. Instead, she’s assuming a style of public media thinking that has become part of the problem, something we need to grow out of and move beyond. I have no trouble understanding the anger that motivated Micah Johnson, as I can understand how his military weapons training boomeranged in his head into a misguided terrorist act. It’s called empathy. Which is not the same thing as sympathy; to empathize means to put yourself in someone else’s shoes — even into their head. It’s an effort to understand, not excuse — versus the usual demonization process and intensifying cycle of violence. There’s a tradition of black veterans as justice-seeking vigilantes. John Singleton’s film Rosewood is about a massacre of blacks in 1923 in Rosewood, Florida, and a WWI black vet played by the imposing Ving Rhames leads an effort to fight back. There’s a couple blacksploitation films from the 70s with the same theme utilizing black Vietnam vets as heroes fighting “the man” back home.

I can also understand what motivated George W. Bush to invade Iraq and take the lives of hundreds of thousands of human beings there. The plot doesn’t seem difficult to grasp: As a leader, he was caught with his pants down on 9/11 and he reacted with “shock and awe” in an unrelated place to bolster a fearsome image. It all went south from there. The point is, while I empathize with both Johnson’s and Bush’s decisions and their accompanying actions, I repudiate them both as criminal. As the Chilcot Report makes very clear about British Prime Minister Tony Blair, these leaders knew what they were doing. They lied their way into an invasion; they were not “misled” by poor intel. Unfortunately, something with the partisan-transcending integrity of a Chilcot Report is unlikely to happen in our culture at this time.

The types of killing being discussed here — state mass killing, individual police killing and individual pay-back killing (some might call it terrorism) — are treated differently in our criminal justice system for obvious reasons, most of them political and involving the relative status of the killer and the victim. On a pure existential level where the meaning-establishing narratives of politics and status we take for granted are removed and life is nothing but a Jackson Pollack confusion of moral chaos, killing is killing, dead is dead and mourning loved ones hurts.

The Muslim spiritual leader who spoke at the very moving grieving ceremony in Dallas on the day after the police killings earnestly asked the crowd why we so often have to wait for such violent and tragic events in order to do something about our problems. His question is a key to all this. I wonder if it has something to do with our philosophy of profit and the free-market and holding out until the absolute last moment lest we make a premature “deal” and give away too much. In that case, violence becomes a punctuation in the process. Boom! It’s time to do something. Everybody at that ceremony in Dallas — white and black, Jew and Muslim — stressed, often with emotion in their voices, we had a real problem in America. The evidence was a week of two senseless police killings of young black men and the inklings of an armed civil war in the making. The fact good people have been screaming ‘til they’re blue in the face for years about this kind of crisis didn’t matter. At the Dallas ceremony, the consensus was if something wasn’t done and done quickly, the nation was in deep trouble. We can only hope this urgency endures beyond the usual mourning period following such incidents.

The remarks made by Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings truly surprised me. My anti-Texas prejudice was not ready for this man, a large white guy who had been CEO of Pizza Hut, a Democrat, who spoke movingly about the need for racial healing, how slavery and other abuses in our history (including the two killings that week) were real — and finally, that there was a need for forgiveness as a way forward. Granted, in his narrative it was white people who needed to be forgiven, but with forgiveness comes atonement, and the mayor seemed inclined to do some needed atoning. Likewise, Dallas Police Chief David Brown carried himself with great humility whenever he showed up before the cameras in the midst of leading the effort to capture or kill Micah Johnson. He spoke of police vulnerability and the need for public support. There was none of the strutting, macho braggadocio made famous by the former president from Texas. The traditional, old-west tenets of vengeance and violent response did not seem to be working anymore in this western urban collective. Something different had to be worked out. And we learned it was already happening: Dallas was in the process of de-militarizing its police into a more community-oriented force. Protesters told of friendly cops in non-SWAT outfits accompanying the Black Lives Matter protest; some cops had their pictures taken with protesters. Dallas cops were actually “protecting and serving” their community — not patrolling it like it was Falluja.

Dallas Chief David Brown, cops after Micah Johnson, and Mayor Mike Rawlings

Dallas Chief David Brown, cops after Micah Johnson, and Mayor Mike Rawlings

As the Muslim religious leader emphasized, it’s at these difficult junctures that people join together to figure out a better way. It’s an uphill struggle, but we can encourage the spirit of forgiveness Mayor Rawlings spoke of. Forgiveness, despite what its slanderous detractors say, is a two-way street focused on difficult dialogue and change; it’s about moving-on with life for the benefit of everybody. It doesn’t work in all cases, but it’s the way of love, a word the mayor and others emphasized over and over that afternoon. Hate gets us nowhere.

I have no need to see George W. Bush in prison; I just want his actions officially recognized as a national disgrace for Americans and, more important, the people of Iraq — so nothing like it will ever happen again. Officer Jeronimo Yanez clearly should be indicted and convicted of homicide; but maybe more important than prison would be some kind of atonement work and the development of a nationally-driven effort to more effectively train police officers like Yanez to better manage their fears. As for Micah Johnson, he chose to avoid trial and went the route of suicide-by-cop, which may be the best justice in his case.

Norm Stamper, the former police chief of Seattle, has a new book out called To Protect and Serve: How To Fix America’s Police. He shows how virtually all police departments are used to collect revenues. Was this a pressure on officer Yanez? The word “quotas” is never used; instead, it’s called “the numbers game.” That is, a cop is told he must deliver two “movers” (moving violation tickets) every day — and more if he’s ambitious to move up in the department. This process was taken to an egregiously oppressive level in Ferguson, Missouri. Stamper also says “the discipline of recognizing and managing one’s fears is not taught in the police academy. Perversely, recruits are taught the opposite. They’re taught to be afraid, very afraid.” He advocates, instead, teaching “the value of knowledge, and wisdom, and self-discipline.” He also points out that police work “does not crack the top ten of the country’s deadliest occupations.” Truck drivers, construction workers and roofers are killed at a greater rate.

Many agree this amazing week is a crisis moment; but it’s also an opportunity to examine the many roots of that crisis. Donald Trump is dead wrong: There’s no going backwards to greatness — except in one’s mind. Life only moves forward toward an uncertain future. Anything else is arguing for a form of mass mental illness that would require even more violence to sustain than the crazy state of exceptionalism we’re in the grip of now. Greatness comes with real self-knowledge.