When you tuck your children in at night

Don’t tell ‘em it’s for freedom that we fight

- Emily Yates

Story is important. It rules our lives without our really knowing it. Some stories amount to unquestioned cultural assumptions; others, we like to argue over. I often introduced the idea of story to the inmates in my prison writing class by pointing out the trial that got them where they were was a forum of dueling stories — and their story lost. The point was for them to want to learn how to better tell their stories.

This is because stories are subject to the realities of Power. One of power’s prerogatives is the establishment of institutions that decide whose story matters and whose doesn’t. Courts, judges and lawyers are the instruments of this kind of power. This court of dueling stories can sometimes become so absurd that it inspires artists like Franz Kafka whose famous novel The Trial is a black comedy about a hapless man facing a powerfully entrenched court system that feels no need to apprise him why he has been taken into custody and why he’s being abused.

Emily Yates with her weapon of choice singing at a fundraiser after her federal conviction for assault

Emily Yates with her weapon of choice singing at a fundraiser after her federal conviction for assault

In the larger courts of Life, Truth and Art, there’s a long tradition of confronting this kind of abusive power of the state. I include the two-tour Iraq veteran and folk singer Emily Yates in this tradition.

Yates lives in Oakland, California, and in August 2013 she had a music gig in Philadelphia. While here, she agreed to be involved in an antiwar demonstration in the Independence Mall area focused on the bombing of Syria. She also agreed to stick around for a later marijuana legalization rally on the mall. It was a blast-furnace August day, so she was relaxing in a corner of the mall with benches under shade trees.

In an incident reported here in September 2013, uniformed and armed men identified formally as US Park Service: Law Enforcement told her and others they had to move. The others were told why, but for some reason, these law-enforcement rangers would not tell Yates why she was being ordered to move. She reminded them it was a public park and said she was not going to move until someone told her why she had to move. She testified in her recent assault trial that she knew US Park Service rangers from parks in Oakland and these people were friendly and helpful public servants. She assumed these men were the same. Just like them, she had done six years of uniformed “service” for her country, in her case in Iraq and elsewhere. She felt she was owed an explanation — for no other reason than human courtesy. She was no longer in the military, and she felt she did not have to respond as if she was. Many veterans like myself recall the familiar drill sergeant in basic training explaining the rules of the game in the military: “When I say ‘Jump!’ you don’t ask me ‘Why?’ you ask me ‘How high?’ ”

Since we live in such a fear-based militarized culture, the law enforcement park rangers that day were not operating in a public courtesy mode. They were geared up in a pumped, militarized mode, possibly envisioning themselves as heroes or maybe warriors for that afternoon. These were not community friendly park rangers from Oakland, and a banjo-strumming chick protesting the bombing of Syria and ready to sing for the legalization of marijuana was simply not due an explanation.

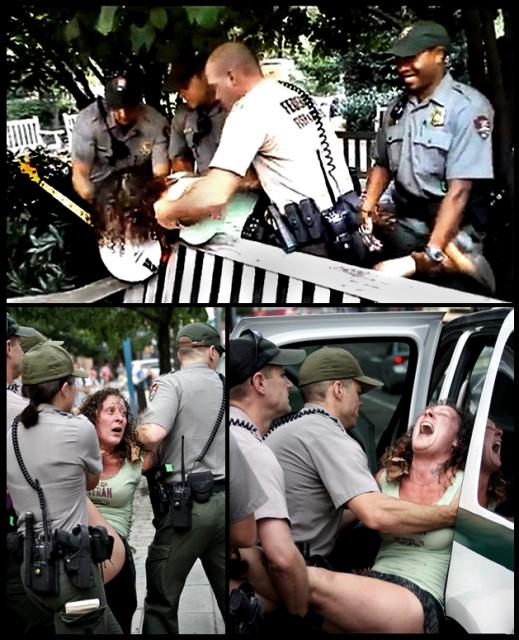

Park rangers assaulting Emily Yates; note the fellow, top, grinning as he holds her legs

Park rangers assaulting Emily Yates; note the fellow, top, grinning as he holds her legs

The facts came out in the dueling stories that was Emily Yates’ two-day federal trial last week. After being kept for 75 hours in Philadelphia’s 7th & Arch Street federal prison tower in August 2013, she had been charged with three counts of assault and one count each of refusing to obey an order and disorderly conduct. Yates’ attorneys argued a PTSD defense and for a reasonable doubt. The prosecutor argued for jail time, suggesting “Ms Yates could do with some more incarceration time to think about what she did.” Federal Magistrate Judge Thomas Rueter listened to the stories from both sides and, at the end of the trial, took ten minutes to arrive at his verdict: Guilty on all counts. Judge Rueter sentenced Yates to a total of three years of federal probation, transferable to California, and a $3,250 fine.

From my vantage point as an antiwar veteran who watched all the video exhibits in court, Yates’ demand for an explanation was legitimate and she was the one physically assaulted, and when, given her PTSD diagnosis, she responded to the blind-side assault as one might expect she would, she was locked up and charged with assaulting her assaulters. Judge Rueter did not see it that way. Instead, he lectured Yates that the rangers all “acted professionally” and that she was lucky they were not more violent like some cops who might have seriously injured her. He uttered not one brief note of criticism for the members of US Park Service: Law Enforcement who battered and dragged Yates, one man shown grinning in delight, around the park for simply wanting to know why she was being told to leave a public area of a public park.

Only one story had any credence in Judge Rueter’s court, and it was the one the federal prosecutor told.

On Saturday, the day following her conviction and sentencing, friends and family held a fund-raising concert for Yates in a home in West Philadelphia. She gave a spirited concert of songs including such on-point tunes as “Talkin’ National Park Service (Beat Your Ass Black &) Blues”, “Try Not To Be a Dick”, “I’d Rather Be High (Than An Asshole)” and the song she said was inspired by a drill instructor who told her, “If You Ain’t Cheatin’ (You Ain’t Tryin’)”.

One can see from this small selection of titles that once Emily Yates got clear of Iraq, the military and militarism, she began to work up a whole different sort of Story to keep herself whole, body and soul. Don’t ask me why; just ask me how high didn’t work for her anymore. As a life-affirming civilian song-writer, she was determined to answer no longer to the obedience-oriented federal militarist machine that had used her for two tours in Iraq. She was now answering to a larger court and thinking in a whole different story line. Chris Hedges wrote eloquently about this at the end of his book War Is A Force That Gives Us Meaning. Here’s Hedges:

“Sigmund Freud divided the forces in human nature between the Eros instinct, the impulse within us that propels us to become close to others, to preserve and conserve, and the Thanatos, or death instinct, the impulse that works towards the annihilation of all living things, including ourselves. For Freud these forces were in eternal conflict. …All human history, he argued, is a tug-of-war between these two instincts.”

Freud developed this theory late in his life at the time of World War One when he was becoming pessimistic and jaundiced about humanity’s instincts for war and killing. It’s not a stretch to see this sort of dialogue of stories at work in the current post-9/11 culture. It certainly lives in the violence that saturates our media. The federal government unfortunately sees itself as having a huge stake in bolstering militarist and creeping police state realities up and down the hierarchy. Emily Yates’ story and her songs of life are rich with the Eros and love of human connection that Freud and Hedges wrote about. Plus, Yates’ personal story is being generated in direct response to the Thanatos/death-obsessed world of the War in Iraq, where she served as a Public Affairs Specialist writing cleaned-up propaganda stories for US consumption.

Right to left: Emily Yates, her husband and producer Eric Yates and a friend in West Philly

Right to left: Emily Yates, her husband and producer Eric Yates and a friend in West Philly

When it comes to the American people at home, the rules of the game in war zones like Iraq are simple. There are two distinct modes of information dissemination vis-à-vis the American public: one is Secrecy and the other is Public Relations. Yates’ job was to churn out the latter. She testified at her trial about going out on a night raid, complete with kicked in doors and fear-up hollering, that ended up abusing the wrong people, innocent people. She was told not to report any of the facts, but to write her PR story as if the mission had been a great success. Being who she is, this began to trouble her. About that time, two male comrades attempted to rape her, and she fought them off.

When she got home and entered counseling with a VA psychologist, she was diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, in her case involving the attempted rape by men supposedly her brothers-in-arms. As many know, sexual assault and rape in the military (on both women and men) is one of the major dirty little secrets of our post-9/11 military. The other involves statistics like 22 suicides a day.

The final Kafka-esque detail of Yates’ federal assault trial is that the Veterans Administration would not permit the VA psychologist who diagnosed her with PTSD to come to Philadelphia to testify on her military-related stress. As her attorney explained to the judge (who would not allow testimony on Yates’ PTSD), the VA did not want its employee to testify against the government.

So here we have a young woman who volunteered to serve her country, who was forced to write lies by the institution she joined and who had to defend herself from an assault by two men with predatory intentions in the war zone where she was serving. She comes to Philadelphia to earn a living singing witty folk songs about love and peace. She’s in the national park that celebrates what a great, free country this is. She simply wants to chill a while in the shade and mind her own business.

At this point, the big, brave men and women from US Park Service: Law Enforcement show up. They refuse to respect her as a veteran enough to tell her they plan to rope off the area she’s in to write tickets for marijuana smokers in the up-coming legalization rally. Instead of informing her of this respectfully — one of the rangers sarcastically told her the reason was “top secret” — they give her an ultimatum. When she still demands an explanation, without any warning that she is about to be arrested, two of the rangers jump her from behind and slam her forward painfully over the back of a park bench. It, then, goes from bad to worse.

One does not need to be a board-certified psychologist to understand this kind of blind-siding behavior can only trigger a volatile response in a young woman traumatized by an attempted rape by fellow soldiers in a virtually lawless war zone. When asked in court what did she do when the rangers jumped her, Yates said, “I panicked.”

Like Emily Yates, the officers of Park Service: Law Enforcement who testified in their starched and tailored uniforms with the black leather pistol belts with all sorts of nifty radios and pouches had their story to tell. It was about duty and service and following orders from above — the classic militarist formula: One does not have the right to ask why; one’s job is simply obedience.

Judge Rueter is a cog in an institution that pays him well and has provided him a fine career. He is respected; he has a story too. Before being appointed a federal magistrate judge, he was an assistant US attorney in Philadelphia from 1985 to 1994; for his last four years he was chief of the Narcotics Section, which makes him a drug warrior. So it’s clear where his professional sympathies lie and what stories move him and shore up his inner world.

Emily Yates singing at a West Philly fund-raising party

Emily Yates singing at a West Philly fund-raising party

At the Saturday fund-raiser for Emily Yates in West Philly, almost $1,000 was raised to pay her fine and whatever attorney fees she owes. (Over $3,000 toward a $10,000 goal has been raised on line so far.) She sang a host of funny, clever songs that made clear her devotion to the truth and a generous love of humanity. The fact her Iraq experiences amounted to a betrayal of that generous love of humanity seems to fuel her work. This makes her and her art that much more important for progressive people to support.

At the fundraiser, she sang a children’s song with the following lyrics:

Life’s not happening AT you; it’s just happening…

When the world goes up in flames,

It’s not crazy AT you; it’s just crazy.

Then she said, “I don’t hold it against those rangers. Apparently, that’s just the way they roll.”

How To Support Emily Yates:

To support Emily Yates, go to the website for her Legal Defense Fund. Then visit her personal website. And go here to hear some of Emily’s songs.