Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

- MacBeth, Act 5, Scene 5

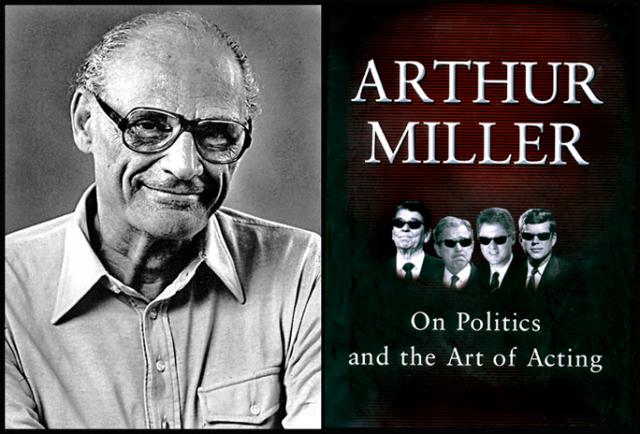

He may not be a very honorable man and he may not lead the most efficient or wisely-run White House, but he sure knows how to act and how to play a fascist on TV. I think this would be the conclusion of the great, deceased playwright Arthur Miller, author of Death of a Salesman, The Crucible and a brilliant little book titled On Politics and the Art of Acting. Miller’s little gem was published in 2001 and was inspired by the election debacle of 2000, an election that a comedian recently pointed out did not suffer from Russian interference; the thumb-on-the-scale interference in that election was home-based and patriotic, provided by a conservative United States Supreme Court.

Playwright Arthur Miller and his 2001 gem on politics and acting

Playwright Arthur Miller and his 2001 gem on politics and acting

I watched the Trump State Of the Union speech on a large cinematic screen at a bar on the Mainline in Philadelphia, part of a “watch party” put on by an environmental activist group my wife works with. With a couple tequilas under my belt, let me tell you, it was total theater of the sort Miller and Shakespeare would appreciate. In this case, it was also a bit like a midnight showing of The Rocky Horror Picture Show with hoots and boos and wisecracks from the assembled audience, all of whom scorned the leading man on the stage. As was often done in the old days of theater, in this case, no one threw rotten tomatoes at the performance. One woman did don earmuffs.

“The mystery of the leader-as-performer is as ancient as civilization but in our time television has created a quantitative change in its nature; one of the oddest things about millions of lives now is that ordinary individuals, as never before in human history, are so surrounded — one might say, besieged — by acting.” This is how the second paragraph of Miller’s book begins. He goes on to say: “I can’t imagine how to prove this, but it seems to me that when one is surrounded by such a roiling mass of consciously contrived performances it gets harder and harder for a lot of people to locate reality anymore.”

This from a man who found it literally impossible to follow in his grandfather’s and father’s path as a businessman, who thus gravitated to the theater and wrote a classic tragedy about an ordinary traveling salesman. Critics said this was impossible; you couldn’t have classic tragedy where the protagonist was not a king or a general, whose tragic fall (caused, of course, by his own decisions and character flaws) was not from a grand and worthy height for great theater, as was associated with Sophocles and Shakespeare. Miller’s Willie Loman was too pedestrian, too common — like most of the people in the audience. (Miller was, of course, a bit of a lefty.) Theater history proved Miller right. What one must wonder these days is, is it possible those always evolving rules of tragic theater apply to someone as pedestrian and common as Donald Trump preposterously elevated into the role of a king, or President of the United States, the position that once (but no more) was known as “leader of the free world”? Miller’s point is that in, this, the 21st century the world has gotten so incredibly complex and convoluted (as philosophy professor Harry Frankfurt would put it, so overwhelmed with bullshit) that the leader of something like The United States of America (or Russia or China, for that matter) cannot possibly tell the truth — or, more accurately, perform as if he were dealing in reality. “Human beings, as the poet said, cannot bear much reality,” Miller writes. “And the art of politics is our best proof.” Bill Clinton, of course, was one of the best politician/actors to come along; his wife, alas, wasn’t nearly as good at the game.

The political acting that Miller writes about was front-and-center in spades last night behind the podium in the exalted chamber of the US House of Representatives. If looked at as mise-en-scene (French for “putting on stage”), the House setting was perfect. The camera lens was framed beautifully on the President as he gave his speech. With his magnificently engineered, gossamer helmet of orange hair and his feral, perfect teeth, he was formally placed against the vertical red-and-white stripes of the flag, on each side of him, two dark chairs holding Vice President Mike Pence looking like Boris Karloff resurrected and the ever-bright-eyed Paul Ryan looking sheepish like he was embarrassed and could envision being drowned in a blue wave. If the camera had pulled back from this tight shot, all the nation would have seen the speech given between two gleaming bookends of bronze fasces. A fasces was an ancient Roman symbol of power — a battle axe surrounded by sticks, which represented the loyal and grateful Roman people — placed atop a pole and carried (probably by a muscular slave) at the head of triumphant processions of Roman magistrates and their bounty. The fasces, as many know, is the root of the word fascism, coined by Benito Mussolini for the movement he led in Italy in the late 1920s.

This is risky business. Making fascist analogies (especially Nazi analogies) is dangerous these days, since it has become a glib bi-partisan exercise. So, let’s be clear: I’m not calling Donald Trump a fascist. At least, not yet. All I’m saying is, in the realm of theatrics, scripting, acting and cinematic mise-en-scene, Donald Trump’s reality show State of the Union speech was classic fascist theater. As an actor, I could not get over how well Trump captured the arrogant, jut-jawed posture of Benito Mussolini; he did it like no other actor I’ve ever seen in the role. Was it George C. Scott who did a turn at Mussolini? Of course, in Trump’s case, this is 2018 and real-time, reality-TV. This was Donald Trump playing himself playing Mussolini.

In Hollywood acting parlance, last night, Trump WAS Mussolini. His chinwork was astonishing!

In Hollywood acting parlance, last night, Trump WAS Mussolini. His chinwork was astonishing!

Cut to Realityland. A nondescript office somewhere in the Justice Department. Robert Mueller is at work late at night, empty pizza boxes on the table, poking and prying into people’s lives to see if he can find evidence of criminal activity. Will it be in the area of collusion with Russians? Will it be money laundering? Or will it be the old standby Watergate favorite, obstruction of justice; in other words, will the political criminal be brought down by his own instinct to cover up a trail of misdeeds that were done in a moment of weakness under the influence of his own arrogance in power? This struggle is going on in the Olympian heights and will likely be wrought into a tragic play or film sometime in the future. Those of us millions of ordinary schmucks — the collective, yet polarized, Willie Lomans in this tragedy — will just have to wait for more shoes to drop as we stay glued to our TVs for the reality-drama. Meanwhile the country will keep going down the old shithole, to coin a phrase.

Alexandr Sokurov is the director of a 1999 Russian film called Moloch. It dramatically focuses on the domestic life of Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun. In his DVD comments, director Sokuroz covers some of the same territory Arthur Miller does. (Here’s a graphic trailer of Moloch, only available for some reason with Spanish subtitles.)

Moloch is a strange film that presumes to tell of a visit by Adolf Hitler in 1942 to his Alpine castle get-away, where a bored Eva Braun awaits him. We first see Braun dancing nude on a precarious parapet of the castle, eyeballed through binoculars by an SS soldier she seems aware of. Hitler is joined by an entourage including a diminutive, rodent-like Joseph Goebbels and his wife and an oafish Martin Bormann. They enjoy dinner-table talk and a bizarre picnic on a rocky mountainside surrounded by SS officers pulling security and servant duty. The film ends with a scene in which the man who captivated masses in Germany and was responsible for the genocide of millions is shown as a sniveling little weasel taunted and seduced by the only person able to speak truth to him. It would be inaccurate to call a movie like this entertainment, and director Sokurov’s long DVD comments make it clear that’s not his intention. He’s interested in power and those who wield it and, through his artistic imagination, to get below the surface to speculate through mise-en-scene and acting what’s at the core of the madness. Hannah Arendt’s famous formulation — “the banality of evil” — hover over this film.

“Every person who tries to seize or holds enormous power, or gets enormous power, inevitably starts acting, inevitably starts inventing a role for himself,” Sokurov says, commenting on his film. “According to his inner psychological abilities and the times, … sometimes it happens that a role is being invented and formed in front of other people. … Hitler is this kind of person, who was actually unable to completely form his role in his performance, and as a tyrant an actor has no director to help him. He directs everything himself, therefore always remains amateur, simply put, unprofessional. Sometimes it’s very funny.”

More often, it isn’t funny. Based on his comments, Sokurov would be the first to agree that directing actors to play real, historic people in intimate moments amounts to fiction, his fictional imaginings and the visceral imaginings of the actors he directs. While Moloch is a far cry from Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, this essay-like example of art cinema is loaded with insight into the dark magic of real-life political theatrics and how a weak and disturbed little man can become a world leader whose specific derangement stirs and provokes the collective mind of masses of human beings with whom his (or her) madness resonates.

But, then, there always is a Resistance. One can only hope the one in our current reality drama can mobilize its power without itself going off the deep end.