I saw the masked men

Throwing truth into a well.

When I began to weep for it

I found it everywhere.

-Claudia Lars

I’m not exactly sure when I became radicalized, but it was sometime in the mid 1980s. I purposely use the term radicalize because, with the rise of globalized insurgency in general and al Qaeda and now ISIS in particular, the word has become a favorite in the media, especially for those on the right, though the New York Times uses it as does Chris Mathews. Sean Hannity at Fox likes to talk fast, and he uses the term over and over like a mantra that sounds good to him.

The problem is they all misuse the word. When it pops up these days, it’s in reference to young American or European “lone wolves” recruited on-line by violent Muslims to join a jihadi organization or, specifically, to be recruited to work for ISIS in Syria or Iraq. The more accurate word for this behavior would be to use the term extremist. Radical refers more to ideas and how someone thinks, while extremist refers to behavior, what someone does.

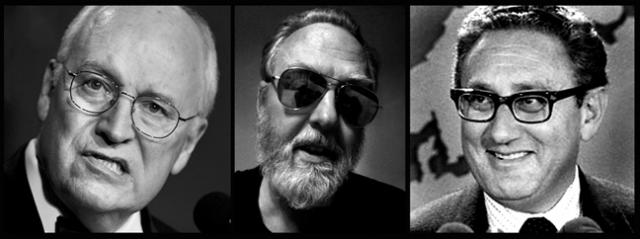

Dick Cheney, the radical author and Henry Kissinger

Dick Cheney, the radical author and Henry Kissinger

I’m a radical; but I’m not an extremist. Using myself, I’d distinguish the terms this way: I think Henry Kissinger and Dick Cheney should be in prison for mass murder, but since this is obviously not in the cards I don’t advocate violent actions be taken against either man. My understanding of the history of the Vietnam and the Iraq Wars is radical in that I refuse to go along with selective propaganda about those wars; I choose not to willfully forget the damning facts about those wars. In this country, that’s a radical frame of mind. The word radical comes from the Latin word radix, which means root. The roots of both those wars are damnable and, if there was real justice, men like Kissinger and Cheney would be prosecuted, convicted and imprisoned.

The facts are clear that the roots of the Iraq war are tangled with premeditated dishonesty and misuse of power; there’s plenty of criminal malfeasance if there was a prosecutor to prosecute. Bringing this radical view right up to the moment, I guarantee (I’m confident saying this) that without that war and the horrors it unleashed in Anbar Province there would be no such thing as ISIS. What the Bush/Cheney/Rumsfeld war did was extremisize the people now unleashing violence and fury in Anbar Province and surrounding areas. (Don’t bother looking up extremisize in your dictionary, because I just made it up.)

So how did I become radicalized? And why wasn’t I extremisized?

What radicalized me was ending up in the mid-1970s a very frustrated young man in inner city Philadelphia. This followed a childhood in rural, redneck south Dade County, Florida, a transplant from New Jersey. There was an influential tour in Vietnam, then an English degree from Florida State University. I came to Philadelphia for graduate school in Journalism at Temple University and ended up staying to work for local inner city newspapers. I had never lived in a city before.

I wasn’t critical of the Vietnam War until I read the history of the war. I was a naïve 19-year-old radio direction finder in the mountains west of Pleiku. My job had been to locate young Vietnamese soldiers opposed to a US occupying army that I was an unwitting part of. I learned my enemy had been a US ally during World War Two, and all they wanted was freedom from the French colonial military that had capitulated to the Japanese. FDR spoke about supporting the de-colonization process; but Truman succumbed to Cold War fears and supported the French desire to re-colonize Vietnam.

Nothing will radicalize a young man more than to learn he had been hoodwinked by his leaders into serving a bad cause.

I taught myself photography. I became an EMT and volunteered at night with an ambulance corps in a mixed-race area of Philadelphia. I fed the homeless in back alleys every Wednesday night, where I enjoyed socializing with other, like-minded people. I read about Central America and joined a group of labor unionists on a trip to Honduras. The unionists asked Honduran officials about reports of the murder and disappearance of union leaders and human rights workers. This disturbed the Honduran government and its US master, which was then up to its neck operating the Contra War against neighboring Nicaragua. We were arrested and deported.

Us and them in Vietnam, "Welcome to Honduras" and ISIS arriving in Anbar Province

Us and them in Vietnam, "Welcome to Honduras" and ISIS arriving in Anbar Province

I was barred from returning to Honduras. But by the early 1990s, I’d made ten trips as a photographer to Nicaragua and into the rebel zones of El Salvador. This stuff really radicalized me. A friend once suggested I was being brainwashed when I went to Central America; she knew this, of course, from watching television. I knew the real reason was it was all wrapped up in the Cold War, that huge political and cultural meta-narrative that had given us the Vietnam War. It was now giving us atrocities in Central America, and I was hearing first-hand the personal, human stories of these atrocities.

Like in Salvadoran poet Claudia Lars’ lines, quoted above, the deeper and deeper I went, the more “I found it everywhere.” The “it” was injustice, brutality and an elite insensitivity to poverty and human suffering. The culprit had many labels: some liked to call it Capitalism; for others, it was social Darwinism; for still others, it was simply a matter of entitlement, a feeling of being more deserving than others, being exceptional, not humbled by being born on third base.

I loved literature as a kid, so I studied creative writing in college and, looking back, I think it made me insist on more moral complexity than we are the good guys and they are the bad guys. I was struck with a bad case of empathy. There was always another way to look at anything and everything: there were different voices for different perspectives. Truth became more important than power as I watched the culture go full-throttle into the post-Reagan age of funny finance. The key factor in my radicalization was a determination not to look away. Our political culture offers an amazing number of opportunities to look away. There’s the material dream, the pursuit of power and all sorts of comforting ideologies and institutions that provide an easy place to hide from discomforting truths. There’s the time-honored Bread and Circus.

As might be expected, my life had not been going terribly well in the money-making realm. Business and entrepreneurial enterprises bored me, though I learned to sell myself as a free-lance photographer and I undertook a number of money-making sidelines like making custom bookcases. I scraped by. It never occurred to me I was abandoning or betraying my class. An editor at a business newspaper once told me: “The trouble with you, John, is you don’t know on which side your bread is buttered.” I’m afraid she was right.

The people I admired in history and current events were people who struggled mightily with ideas and with crafts like writing and photography, using them to dialogue with the real world. I began to see one of the strengths of the class I came from was the ability not to see things that might encumber or slow down upward mobility or cut into the profit margin. Of course, I did my time looking to the poorer classes for authenticity.

The 2000 election debacle in my home state of Florida further radicalized me. I was naïve enough to think national presidential elections could not be stolen. But I watched Al Gore and the mainstream media cover their eyes to avoid conflict, and Bush v. Gore was hidden away in a trunk in the cellar like a bullet-riddled corpse they didn’t know what to do with. We still get fetid whiffs from that cellar. I’m not an Al Gore fan, but there’s little doubt a Gore presidency would not have taken the nation so far off the rails. It’s radical to remember this stuff.

Then, 16 Saudi Arabians angry at our imperial relationship with the obscenely rich Saudi oil potentates hijacked planes full of jet fuel from Saudi Arabia and flew them into our iconic buildings. We suddenly had an illegitimate government raging on adrenaline. A less-than-astute president and his managers saw an opportunity. In September 2000, the far-right think tank The Project For a New American Century had published a 90-page report called Rebuilding America’s Defenses advocating militarist scenarios that included attacks on Iraq and Syria. In Subsection V, “Creating Tomorrow’s Dominant Force,” it included the following: “[T]he process of transformation, even if it brings revolutionary change, is likely to be a long one, absent some catastrophic and catalyzing event––like a new Pearl Harbor.” The top Bush people were radicals on the far right. They were also extremists, the children of Barry Goldwater who in 1964 had famously said, “Extremism in the cause of liberty is no vice.” Goldwater was wrong; extremism is a vice. And that moment had arrived.

I don’t subscribe to theories about US complicity in 9/11. For me, the indisputable facts are rotten and conspiratorial enough. During the Iraq War, I made two trips into Iraq to see for myself. One trip was with veteran peace activists and another was as a cameraman on a documentary film. These trips entailed four 12-hour treks by large SUV between Ammon, Jordan, and Baghdad through the vast and inhospitable desert of Anbar Province. This is the area routed by ISIS and now known as The Islamic State. I had tea and kabobs in truck stops among pro-Saddam Sunni Arabs, some who are now no doubt part of ISIS.

Strange bedfellows are a hazard in the radical area. Glenn Beck of all people is on record against renewed war in Iraq. “Not one more life! Not one more dollar!” he says, meaning no US military involvement in Iraq.

“The people of Iraq have got to work this out themselves,” he said on his show. “Our days of being the world’s policeman, our days [as] interventionalists is over. If we are directly attacked, so be it. But this must end now. Now, can’t we come together on that? Are we not all a people that can come together on that?”

It’s like waking up in the morning in bed with the monster from Alien.

Like a classic radical, Beck emphasizes the reading of history, especially in this case the 1916 Sykes-Picot Treaty that carved up the Ottoman Empire after WWI between the English and French and, ignoring ethnic realities, created an Iraq controllable by the Brits. At the end of Lawrence of Arabia, Claude Rains plays a slimy fictional composite of Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot. About his scheming politics, he says: “A man who tells lies, like me, merely hides the truth. But a man who tells half-lies, has forgotten where he’s put it.” Dick Cheney would understand this man. George W. Bush would be the other guy, the half-liar who has no clue what the truth is and doesn’t care — one of philosopher Harry Frankfurt’s modern bullshitters.

Given the notion of strange bedfellows and the across-the-aisle radical dialogue Beck and some libertarians suggest exists, the possibility of educating Americans about the costs of militarism becomes an interesting possibility. That’s the thing about radical ideas, at some point they begin to make sense to a wider swath of people, and they don’t feel so “radical” any more. Sometimes a critical mass is reached, and a radical idea can lead to the fall of an empire like happened to the Soviets. The US Government and the Pentagon must live in terror of this.

I’m part of a group of decent radical American veterans concerned that the US government’s upcoming 50th anniversary of the Vietnam War fairly represent that war. Given the government’s inclination so far to turn the anniversary into a glorification of US suffering and heroism, those raising moral questions about the war seem destined to be classified as radicals and, thus, shunned. Me, I’ll proudly accept the epithet radical. Individual bravery and suffering should certainly be recognized; but the record must show the truly dark side of the Vietnam War. A one-sided fiction of glory can too readily be used to promote future bad wars. The history of the Vietnam War should be a moral cautionary tale.

So the final question: why wasn’t I extremisized?

Nadezhda Tolokonnikova of Pussy Riot explains it best. It has to do with humility and a true desire for peace. Tolokonnikova’s non-violent actions led to her doing real time in one of Russia’s most dreaded prisons. She had no interest to chop anybody’s head off or to bomb anyone. Based on a radical analysis, she and her band confronted Russian cultural taboos and raised important public questions. In a letter to Tolokonnikova in prison, the Slovenian writer Slavoj Zizek said this of her and Pussy Riot: “[Y]ou know very well what you don’t know, you don’t pretend to have fast and easy answers, but what you are also telling us is that those in power don’t know either.”

Pussy Riot, left to right, Yekaterina Samutsevich, Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, and Maria Alyokhina

Pussy Riot, left to right, Yekaterina Samutsevich, Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, and Maria Alyokhina

Tolokonnikova responded by elaborating on the humility at the root of her radicalism:

“The main thing is to realize that you yourself are as blind as can be. Once you get that, you can, for maybe the first time, doubt the natural place in the world to which your skin and your bones have rooted you, the inherited condition that constantly threatens to spill over into feelings of terror.”