I saw the masked men

throwing truth into a well.

When I began to weep for it

I found it everywhere.

– Claudia Lars (El Salvador)

Those of us who have struggled for peace and justice over the past decades don’t have much to celebrate these days. But the news from Guatemala that a female judge — Yasmin Barrios — was able to successfully manage a trial in that benighted nation and convict former President Efrain Rios Montt of genocide is something to rejoice about. It suggests it’s no longer business as usual in Latin America — especially vis-à-vis the United States.

The big stick of North American imperialism from Teddy Roosevelt to Ronald Reagan appears to be dwindling in size. The sentencing of a Guatemalan president to 80 years in prison for employing scorched earth tactics against native Mayan Indians is an amazing milestone — and an incredible story to boot.

Following a 1954 US-directed coup that overthrew democratically elected President Jacobo Arbenz for his efforts at agrarian reform, the tiny Central American nation descended into a condition that can only be characterized, for the native Mayan people, as a state of Hell-on-Earth. The fact that President Rios Montt undertook his systematic slaughter of many thousands of Mayan peasants with the endorsement of Ronald Reagan only makes the conviction that much sweeter.

.

.

In the photograph, at left, Ronald Reagan, “the Great Communicator,” meets with Rios Montt, who is holding a document titled “This government has the commitment to change.” At the time, Reagan said Rios Montt was “a man of great personal integrity and commitment” who wanted to “promote social justice.” At right, is a line of bodies from one of the Guatemalan army’s massacres of people who, no doubt, were deemed “communists” and, therefore, inhuman and justifiably slaughtered like vermin.

Army General Efrain Rios Montt became president of Guatemala thanks to a coup in March 1982. He was, then, deposed by another coup in August 1983. This was a time when Mr. Reagan was hypnotizing the American people with his aw-shucks, soothing Hollywood narcotic speech tones.

Previous to the supportive Reagan administration, the Carter administration had cut off military aid to the Guatemalan military. But, then, our representatives in Washington cut a deal with Israel to arm the Guatemalan army and, thanks to lots of experience with Palestinians, to teach them how to monitor and keep track of the Mayans utilizing computerized records and other hi-tech tricks. Rios Montt reportedly once told ABC News that his success was due to the fact that “our soldiers were trained by Israelis.”

What arguably prepared the ground for the Rios Montt trial was the 1998 murder of Bishop Juan Gerardi, bludgeoned to death by a cinder block in his garage in Guatemala City. Gerardi directed the Guatemalan arch-diocese’s human rights agency, known by the acronym ODHA. Two days before his murder on April 26, ODHA had released a document titled Nunca Mas or Never Again, a four-volume document that detailed the horrors of the 70s and 80s.

Francisco Goldman followed the case for years and wrote an incredible account called The Art of Political Murder: Who Killed the Bishop? It is a labyrinthine and bizarre tale complicated with death threats, charges of homosexual priests and a German shepherd named Baloo. After three years, three military men were convicted and sentenced to thirty years each for the murder. During the trial, one of those men, Colonel Byron Disrael Lima Estrada, said he was “just the point of the spear. Once they’ve created a judicial precedent, then they’re going to go after the others.”

“For half a century the military’s clandestine world had seemed impregnable,” Goldman writes. “The Gerardi case had opened a path into the darkness.” The bishop had been murdered because his work for the poor of Guatemala had directly threatened the “clandestine underbelly of official power — and their criminal rackets.”

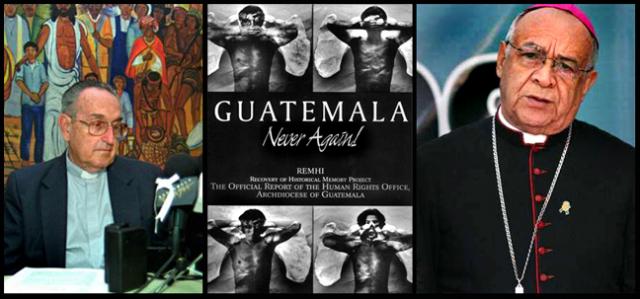

Murdered Bishop Juan Gerardi, left, ODHA's Nunca Mas report, and Bishop Mario Rios Mont

Murdered Bishop Juan Gerardi, left, ODHA's Nunca Mas report, and Bishop Mario Rios Mont

The Gerardi story literally intersects with the Rios Montt story. With the death of Bishop Gerardi, the archdiocese appointed the brother of Efrain Rios Montt — Catholic Bishop Mario Rios Mont (unlike his brother, he spells his surname with a single “t”) — as director of ODHA, the human rights office. It seems the two brothers were diametrically opposed on the politics of the poor, with Mario assuming some liberation theology views. This may explain why General and President Rios Montt abandoned Catholicism and became a born-again evangelical protestant using apocalyptic language out of The Book of Revelations. At the time, Rios Montt was a personal friend of Pat Robertson. (You may recall it was Robertson who on TV publicly called for the assassination of Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez.)

In what now seems a weirdly prescient remark, during the Gerardi murder trial Bishop Rios Mont said this, referring to the Guatemalan military’s immense clandestine power: “…as long as this power behind the throne exists, Guatemala will not be free, nor will it have justice or peace. Here, presidents come, and presidents go. Just when we thought we’d recovered an environment that made it possible to live in peace, they answered: Here take your dead man, who tried to discover the truth.”

I made ten trips to Central America in the 1980s and ‘90s as a documentary photographer. It was a time when anyone trying to call attention to this kind of violence could get nowhere in North America. I knew of the slaughter in Guatemala, so it’s hard to swallow the idea that the US government did not. The Reagan administration came in denouncing the Carter human rights focus and began to aggressively stir up war in the region. It armed and trained ex-soldiers of the Nicaraguan tyrant Anastasio Somoza’s dreaded guardia in what became known as the Contra War. Reagan’s highly publicized labeling of the Contras as “freedom fighters” aside, it was basically a terrorist war of hit and run attacks on pro-Sandinista villages and enterprises, with the Contras being directed out of neighboring Honduras by US Ambassador John Negroponte.

The US sent advisers to El Salvador, and as the death squad bodies piled up, the Reagan administration certified every six months that improvements were being made.

Having spent time in Central America then and having met so many wonderful people trying to free themselves of the yoke of oppression, the only downside to the conviction of Rios Montt for genocidal murder is that Ronald Reagan can’t be given a similar trial and packed away to some super-max in the desert. Sure, I carry some bitterness from those years. They were extremely frustrating times for anyone with any compassion for the poor in Central America.

I recall trying to explain to my Reagan-loving father what it was like to listen to a Salvadoran woman tell about finding her 23-year-old daughter in a body dump tortured and skinned. I’ll never forget the sadness and horror in her eyes as she willed herself to share her horrific tale so we visiting gringos might pass it North.

When I told my dad of this stuff, he would grimace at his rebellious middle son — not because of the story or the woman’s suffering, but as if he were echoing Ronald Reagan: “There you go again!” The more horrible the story, the more I was dismissed as a dupe of left wing communists. It was impossible to get through the point that we were supporting and condoning monstrous behavior. Suffering that was connected to our policies simply did not register. I recall a workmate who suggested one day at lunch that because of my traveling in Central America I knew less than she did from watching television.

It really began to sink in that the most powerful nation in the world was nursing a deep mythic assumption that Americans and America were exceptional; somehow we were being victimized by these little countries in Central America. The peasants being consumed by incredible violence deserved whatever they got for what they had done to us.

A shrink might point out that we North Americans had done our own versions of scorched earth in bombing campaigns in Vietnam and Laos. We did this because the Vietnamese refused our demands that they capitulate and give up the idea of independence. They would not budge, so we had to bomb them. They were trying to humiliate us in the world’s eyes, and we had to stand up to them.

How long can we delude ourselves with the Myth of Exceptionalism? How many more massacres and bombing atrocities do we have to refuse to see before the scales fall from the eyes of a critical mass of Americans? How much more bullshit do we have to take?

.

.

The photos, here, show three Mayans who testified to atrocities in the Rios Montt trial. They are, from left to right, Juana Sanchez Toma; Benjamin Jeronimo, president and legal representative of the Association for Justice and Reconciliation that advocated for the trial; and Elena de Paz Santiago, who told of being beaten and gang-raped repeatedly by soldiers. Jeronimo told the blog democraticunderground.com that young Guatemalans “have to know what a dirty war is, a war in which people were taken advantage of, who had no way of defending themselves, and were not guilty of what they were being accused.”

“We showed them we are not communists,” Antonio Caba told The New York Times as he wiped away tears. “We are simply villagers.”

The conviction and sentencing of Efrain Rios Montt to an effective life prison term is an important milestone. Something has been broken and overcome in Guatemala. While the Guatemalan right is certainly not without resources, the poor have clearly gained a degree of power in a very dark system.

Ricardo Falla, a Jesuit priest in Guatemala, wrote a powerful book called Massacres In the Jungle: Ixcan, Guatemala, 1975-1982 documenting all the horrors revealed in the Rios Montt trial. He writes, “Seeds of new life have emerged from the massacres.” He metaphorically refers to the horrors as “fertilizer that makes the earth fruitful, blossoming with something new.” A strong bond has been formed out of horror. “Weeping is accompanied by another sign of life: the feeling of brotherhood, which overrides family, language, and ethnic and religious barriers — their shared bond as people who have lost everything.”

As a nation and a people, we don’t know anything about victimhood, and it’s past time we moved beyond that delusion.