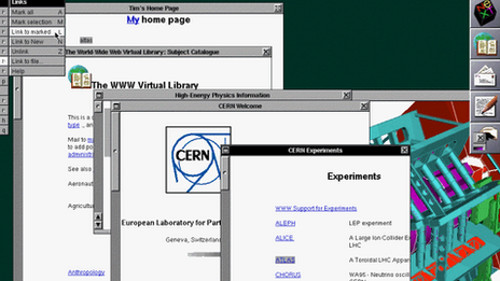

This Summer, a team at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) has undertaken a remarkable project: to recreate the first web site and the computer on which it was first seen.

It’s a kind of birthday celebration. Twenty years ago, software developers at the University of Illinois released a web browser called Mosaic in response to work being done at CERN. There, a group led by Tim Berners-Lee had developed a protocol (a set of rules governing communications between computers) that meshed two basic concepts: the ability to upload and store data files on the Internet and the ability of computers to do “hyper-text” which converts specific words or groups of words into links to other files.

They called this new development the “World Wide Web”.

The Original Web Pages

The Original Web Pages

When you read Berners-Lee’s original proposal you get a feeling for the enthusiasm and optimism that drove this work and, since it’s all very recent, the people who did it are still around to explain why. In interviews, Sir Tim (Berners-Lee is now a Knight) insists he could not foresee how powerful his new project would be but he knew it would make a difference. For the first time in history, people could communicate as much as they want with whomever they want wherever they want. That, as he argued in a recent article, is the reason why it’s so critical to keep the Web neutral, uncontrolled and devoid of corporate or government interference.

In our convoluted world of constantly flowing disinformation, governments tell us the Web is a “privilege” to be paid for and lost if we misbehave, corporations tell us they invented it, and most of us use it without really thinking much about its intent. Very few people view the World Wide Web as the revolutionary creation it actually is.

Whether its “creators” or the vast numbers of techies who continue to develop the Web think about it politically or not, there is an underlying understanding that unifies their efforts: The human race is capable of constructive exchange of information which will bring us knowledge all humans want and benefit from and in collaborating on that knowledge, we can search for the truth. There is nothing more revolutionary than that because the discovered truth is the firing pin of all revolution.

Twenty years later, it’s painfully ironic that, when they hear the word “Internet”, most people probably think of Social Networking programs like Facebook and Twitter. As ubiquitous and popular as Social Networking is, it represents a contradiction to the Internet that created it and to the World Wide Web on which it lives. It is the cyber version of a “laboratory controlled” microbe: it can be and frequently is productive but, if used unchecked and unconsiously, it can unleash enormous destruction, reversing the gains we’ve made with technology and divorcing us from its control.