An investigative arm of the Pentagon has termed Wikileaks founder and editor-in-chief Julian Assange, currently holed up and claiming asylum in the Ecuadoran Embassy in London for fear he will be deported to Sweden and thence to the US, and his organization, both “enemies” of the United States.

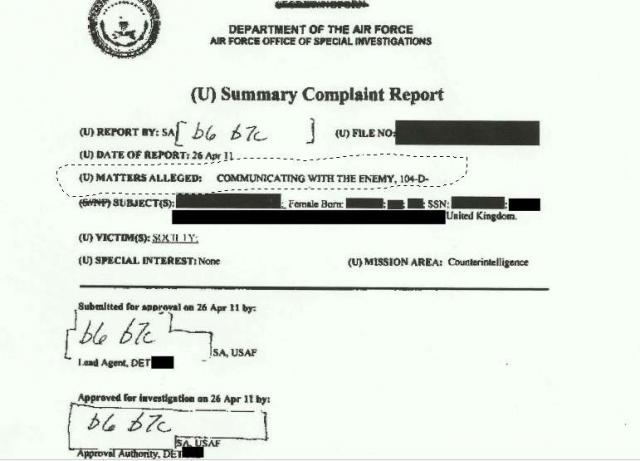

The Age newspaper in Melbourne Australia is reporting that documents obtained through the US Freedom of Information Act from the Pentagon disclose that an investigation by the Air Force Office of Special Investigations, a counter-intelligence unit, of a military cyber systems analyst based in Britain who had reportedly expressed support for Wikileaks and had attended a demonstration in support of Assange, refers to the analyst as having been “communicating with the enemy, D-104.” The D-104 classification refers to an article of the US Uniform Military Code of Military Justice which prohibits military personnel from “communicating, corresponding or holding intercourse with the enemy.”

This is pretty dangerous language, referring to an Australian citizen who many consider to be no more than a working journalist who has been receiving information leaked by whistleblowers and disseminating that information to the public. As David Cole, a civil liberties attorney in the US associated with the Center for Constitutional Rights, notes, “The US military is not at war with Wikileaks or with Julian Assange.”

Certainly if a member of the US military were to go to a news organization like the New York Times — or the Melbourne Age for that matter — and leak some kind of damaging secret information exposing US military war crimes, it is hard to believe that the military would call that “communicating with the enemy” (though reportedly the Bush/Cheney administration considered, but then dropped the idea of bringing espionage charges against Times reporter James Risen for publishing in his book secret information about the government’s bungled effort to pass faulty A-bomb fuse technology to the Iranians). In any case, a military leaker could easily be charged under the military code with offenses like revealing national security secrets or some other serious charge, which would not involve charging any media organization that received the information.

The decision by the Pentagon to instead use the D-104 code to classify Assange as an “enemy” in this context is dangerous because since 9-11-2001, the US government, with the general consent of the courts, has been treating “enemies” of the state in some very frightening extra-judicial ways. Enemies of the US these days can be summarily arrested and carted away to black-site prisons or to a place like Guantanamo without even a requirement that any notice be given to friends or relatives. They can be locked up indefinitely and denied access to a lawyer. They can even be subjected to what is euphemistically called “enhanced interrogation,” which most people, and which international law, call torture, as was done to Private Bradley Manning, charged with providing hundreds of thousands of pages of secret documents to Wikileaks.

Here's the page from the Pentagon file that labels Assange and Wikileaks as "enemies" of the US

Here's the page from the Pentagon file that labels Assange and Wikileaks as "enemies" of the US

Says Ratner of the FOIA materials, “Almost the entire set of documents is concerned with the analyst’s communications with people close to and supporters of Julian Assange and Wikileaks, with the worry that she would disclose classified documents to (them). It appears that Julian Assange and Wikileaks are the ‘enemy.’ An enemy is dealt with under the laws of war, which could include killing, capturing, detaining without trial, etc.”

But Ratner notes that the classification of Assange as an “enemy” doesn’t just threaten him. “It threatens the press too,” he says, which is thus seen as an agent of Assange. “They used the same D-104 charge against Manning,” Ratner explains, “and in court the government explained that when Manning (allegedly) provided secret military documents to Wikileaks, and that information was then made publicly available, including presumably to Al Qaeda, both he and Wikileaks were ‘aiding’ terrorism.” Ratner says this is the same kind of guilt-by-unintentional-association argument that is also used in saying, as the US now does, that if a person innocently gives money to a charity that then itself passes some of the funds on to another charity that is, perhaps even secretly, aiding Al Qaeda, the original donor can be prosecuted for aiding Al Qaeda.

“What the government is doing here,” says Ratner, “is saying that it is the news organization’s legal responsibility to decide what it is legal to publish, and what might, if published, constitute an act of ‘aiding terrorism.’”

News that Assange was labeled an “enemy” by the US (important information that has not been reported in any of the corporate US media), casts in a darker light rumors in the US and Australia that the US has already obtained a secret sealed indictment of Assange, and that it is trying to engineer his deportation from Britain to Sweden, where he is wanted by prosecutors for questioning concerning two controversial complaints of sexual assault, so that he can be then more easily extradited to the US.

A British court has already approved his extradition to Sweden, but as he was awaiting his last appeal, Assange jumped bail and fled to the Ecuadoran Embassy, which granted him asylum and said he is welcome to come to Ecuador–if he can get there. Britain has vowed to arrest him if he leaves the safety of the embassy, leaving him at least temporarily stranded in the building.

Many observers believe that the long captivity, including torture, and the delayed military prosecution of Pvt. Manning, all widely condemned including by the United Nations reporteur on human rights, is aimed at trying to coerce him into trying to cut a deal for a reduced sentence by fingering Assange as having lured or bribed him into revealing secret military documents — something Assange denies, and which Manning has refused to do.

Word that the US government, or at least the Pentagon, is considering Assange and his organization to be “enemies” of the US would appear to make his fear of extradition to Sweden, as well as the British authorities’ zeal to arrest him and hand him over to Swedish authorities, all the more justified. Sweden has an easier procedure for extraditing people to other jurisdictions for prosecution than does Britain, and currently has a right-wing government that is very supportive of US military and war policies.

Significantly, offers by Assange and by Ecuador to allow him to be questioned freely by Swedish prosecutors about two incidents of alleged unwanted sex asserted by two Swedish women have been declined by Swedish authorities, again raising suspicions that the extradition is all about getting Assange out of Britain and into Sweden. He has not been charged there with any sex offenses, and is only sought for questioning.

The Age is no supporter of Assange in Australia, though it did obtain and publish many of the leaked documents from Wikileaks that have angered US authorities — military reports of war crimes, and embarrassing secret diplomatic cables — but the latest revelations did lead the newspaper to publish an editorial noting that calling the Australian Assange an “enemy” was putting him in “the same legal category as the al-Qaeda terrorist network and the Taliban insurgency.” It goes on to note that two other Australian citizens, David Hicks and Mamdouh Habib, “endured long detentions without charge at Guantanamo Bay until a special military tribunal was set up to try detainees. That points to the risks for anyone declared an ‘enemy’ of the US military.”

The paper urges the Australian government, which to date has taken a hands-off attitude towards Assange’s plight (actually, Australia’s Labor Party Prime Minister Julia Gillard controversially asserted after Wikileaks’ big document dump that the releases had been “illegal” and “grossly irresponsible”), to instead “stand firm against any US moves to treat Assange as a military enemy or as a spy operating for the enemy,” adding, “That would make him a martyr for free speech.”

Many people around the world believe that he is already that.