Anthropologists have found that in traditional societies, memory becomes attached to places.

T.M. Luhrmann, New York Times Op-ed May 25, 2015

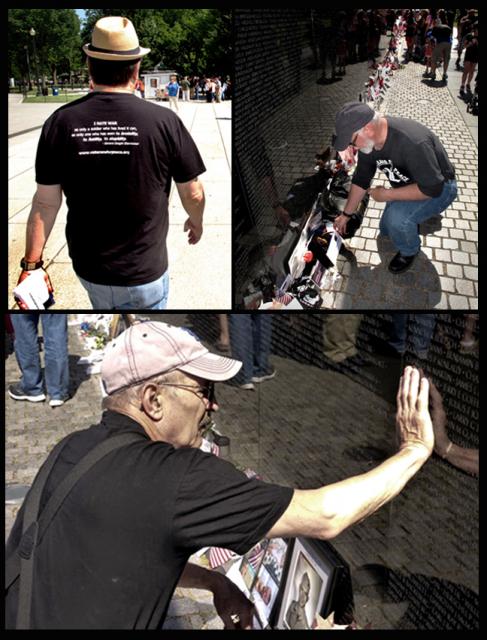

Members of Veterans For Peace came from as far away as San Diego to be part of the annual Memorial Day ceremonies at the Vietnam War Memorial on the mall in Washington DC. A wide range of Americans were in attendance on a beautiful, sunny day. Some rubbed names of loved ones with pencils onto pieces of paper; others left significant items at the base of the Wall. These are collected and warehoused.

Vietnam veteran poet Doug Rawlings from Maine devised a program called Letters to the Wall. It’s an on-going project of Full Disclosure, which is connected to Veterans For Peace. Full Disclosure was created to counter the current US government and Pentagon propaganda campaign commemorating the Vietnam War. The project, operated with $15 million-a-year in tax-payer funds, was begun on the 50th anniversary of the Marine landing in DaNang in March 1965.

Full Disclosure members attempted unsuccessfully to meet with Pentagon managers of the program to discuss the limitations of its website, especially a timeline of events concerning the war. The timeline emphasizes things like Medals of Honor awarded to US soldiers, but it leaves out much of the complexity and the unpleasant realities of a war that began at the close of World War Two in 1945 when US leaders chose to support French re-colonization of Vietnam. Vietnamese guerrillas were US allies against the Japanese and admired their American comrades-in-arms. After the French capitulated, the war went on until 1975, when the US left Vietnam. Going through the website and reading the timeline, it’s easy to get confused and think that the Vietnamese somehow attacked us and that our soldiers were responding bravely to being attacked. Indisputable historic facts such as how the agreed-upon unification elections designated for 1956 were scotched by US leaders (who knew Ho Chi Minh would win by up to 80% of the vote) are altogether missing on the Commemoration website. The overwhelming reality that US soldiers were sent halfway around the world as an occupying army is lost in the interest of honoring the courage and sacrifice of Vietnam veterans.

Here’s how Rawlings described the letter project for those interested in writing a letter:

“Let those American soldiers who died know how you feel about the war that took their lives. If you have been seared by the experience of the American war in Vietnam, then tell them your story. Veterans, conscientious objectors, veterans’ family members, war resistors, anyone whose life was touched by the war — all of us need to speak. All of our experiences matter.”

One hundred and fifty letters were collected, and at 11 AM on Memorial Day, VFP members walked to the Wall and dropped them at the base of the panels, along with all the other items left there. On the envelope, written by hand, each letter said: “Please Read Me.” The letters are all collected on-line.

Besides tourists and families, there were many Vietnam veterans at the Memorial Day event. A dozen or so Medal of Honor recipients from the war were on hand. The keynote speech was given by retired Colonel Jack H. Jacobs, a Medal of Honor recipient. His remarks were surprisingly short compared to the other speakers, and like all but one speaker, he emphasized how those named on the Wall died fighting for freedom here in America. The exception was Diane Carlson Evans, a nurse who served in Pleiku; she spoke of veteran suicides and other painful post-war problems that still linger. She received the longest standing ovation. She was followed by a representative of the US Postal Service who unveiled three new “forever” stamps featuring the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Clockwise, Navy color guard, Col. Jack Jacobs, Diane Carlson Evans and audience members. Photos by John Grant.

Clockwise, Navy color guard, Col. Jack Jacobs, Diane Carlson Evans and audience members. Photos by John Grant.

As a Vietnam veteran (I was a 19-year-old radio direction finder who located Vietnamese radio operators, so they and their comrades could be killed), I have no issue with honoring the sacrifice and bravery of men and women who served in Vietnam. Even in a bad, unnecessary war, these qualities exist alongside cowardice and atrocity. Fifty-eight thousand names are on the wall, a great many of them drafted. There were also many young men just like me, who volunteered and went to Vietnam clueless as to what it was about, what it meant or why you were even there. I was lucky and had it pretty easy. Still, there were a few times if things had gone badly for me I might have been killed. My name could have made it onto that Wall. This gives me and others like me a voice and a right to express views that may differ from the standard line. All that’s required is it be done in a dignified manner.

In a New York Times op-ed on Memorial Day, anthropologist T. M. Luhrmann described the Vietnam Wall this way: “When the Vietnam Veterans Memorial opened in 1982, people were startled to find the black gash in the earth and its list of names so moving. And then they started to leave things at the wall — letters, cards, photographs, votive candles, a teddy bear, cans of fruit salad. Some of these items seem like attempts to talk with the dead, but others seem like ways of being present, or ways of making the memorial in some small part something they themselves have made. The objects seem to say: These men are gone, but with this gift we are part of one another. It is easy in our individualistic culture to think of memories as private and selves as interior. That is an illusion. Our memories and dreams dwell incarnate in the world.”

As a nationally recognized, public space, members of Veterans For Peace feel it’s important that our view of the war be represented at the Wall at national, public events like Memorial Day. There is no intention to be provocative; it’s a simple fact that many Vietnam veterans don’t share the belief that those on the Wall died fighting for our freedom here in America. It’s my understanding that most combat veterans would argue that when in combat one fights for survival and for one’s brothers-in-arms — not freedom at home. The fighting-for-freedom line is a conformist response based on the desire that one’s sacrifice and experience be recognized as part of a noble effort. It’s also part of the Pentagon’s desire to put a good spin on its wars. To willfully ignore the unpleasant realities of the war and the terrible things done to the Vietnamese who never threatened Americans can only make future wars easier to engage in.

A number of people were seen opening and reading the letters left at the base of the Wall. One young woman sitting with a friend at the base of the wall reading the letters said she was very moved. She thanked us for the project.

A range of affinity organizations produced flower wreaths to be symbolically set up in front of the Wall. We had one representing Veterans For Peace and Swords Into Plowshares. Wearing Veterans For Peace and Full Disclosure t-shirts, behind two vets from a motorcycle club, two us placed the wreath at the Wall. As one might expect, we received some glowering looks. The point was to publicly and respectfully represent a counter-view to the prevailing message of the day. We wanted to represent the range of Americans who believe the Vietnam War had absolutely nothing to do with freedom in America and that the full, unvarnished history of the war needs to be fully disclosed and discussed.

As many Veterans For Peace members expressed, it was a good day.

Clockwise, Mike Hearington, Doug Rawlings and Tarak Kauff. Photos Grant & Davidson

Clockwise, Mike Hearington, Doug Rawlings and Tarak Kauff. Photos Grant & Davidson

VFP members and a Swords To Plowshares Memorial Bell Tower made by Roger Ehrlich of Raleigh, NC

VFP members and a Swords To Plowshares Memorial Bell Tower made by Roger Ehrlich of Raleigh, NC