As gullible North Americans were told of disease-ridden Mexican and Central American rapists, killers and ISIS terrorists invading America from the infernal regions of the western hemisphere, on November 17 and 18, Veterans For Peace and other activist organizations sponsored a two-day border-straddling demonstration in Ambos Nogales, the term that covers both Nogales, Arizona (population 20,000) and Nogales, Sonora, Mexico (population 220,000).

Speaking for myself, every Mexican or Central American I ran into, saw on TV or read about as part of the caravan phenomenon was clean and quite nice. Having spent time in Honduras in the 1980s I’m aware of the cruel and bloody aftermath of the 2009 coup in Honduras that President Obama and Secretary of State Clinton covered over like a cat covering its business. The only difference between them and Trump is that Trump’s in-your-face, cruel lack of empathy, in this case, is more honest. The well documented historic record shows our behavior vis-a-vis poor Central Americans — especially Hondurans — has put these poor people between a rock and a hard place. This has now come to a head with people running for their lives and slamming into a hostile US border in Tijuana. The same tensions are felt in Ambos Nogales, a border-straddling community cut in half by an obscene steel wall — shown, below, from the Mexican side.

(For an account explaining the caravan issue from a Honduran perspective, go to Amalie Frank-Vitale’s Fortune Magazine piece called “I Live in Honduras, Where People Are in Constant Fear of Being Murdered. It’s No Wonder They Join Caravans.” Dana Frank, professor emerita at the University of California, Santa Cruz, has just published an excellent book that details the violence that followed the 2009 coup; it’s called The Long Honduran Night. Click here for an interview with Dana Frank by Amy Goodman.)

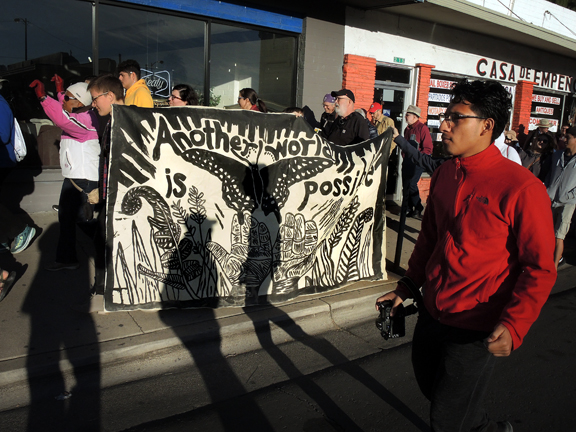

This is the third year of the Encuentro, which involved up to 500 people from all over the United States and Mexico. As in past years, it was a demonstration (or manifestacion in Spanish) that was split between the US and Mexico with a stage on the Mexican side of the wall made up of 20-foot-tall rusting, square steel poles four inches apart. In the past, one could reach a hand through to a person on the other side or even stick your face through to kiss another, if that was in order. But no more: This year, the US Border Patrol had put up rigid steel meshes to prevent that; they also installed a steel fence ten feet from the wall on the US side, preventing people from getting next to the wall. This, however, did not stop people from effectively doing civil disobedience and going up to the wall.

On the US side of the demonstrations on Saturday and Sunday, Border Patrol SUVs kept an eye on the peaceful demonstrators. The Border Patrol agent I spoke with spent the day parked (above) overlooking the demonstration. The man seemed quite bored. He explained to me that the steel meshes all over his SUV were because, “They like to throw rocks at us.” This SUV was parked at the spot where, across the border in Mexico, there is a large painting of 16-year-old Jose Antonio Elena Rodrigueza (top) who was shot dead in 2012 by a US Border Patrol agent for throwing rocks through the wall. The agent was charged with second-degree-murder but was acquitted in April. It was 11PM; the agent claimed there was drug activity in the area and that he was scared due to the rocks coming at him; he emptied his pistol and re-loaded, firing a total of 20 rounds — 10 of them hitting the boy. The Border Patrol agency has gone from 4000 agents in the late ‘90s to over 21,000 currently.

The Encuentro was a festive affair with puppets, bands and speeches. The spirit of the manifestacion could be characterized by the idea of Ambos Nogales, a historic community that may straddle a national border but is in reality a place of international dialogue and human exchange, a place where a distinct, rigid border separated by a tall steel wall is resented by those living near it — a situation that must necessarily be enforced by violence, something that explains the ridiculous death of Jose Antonio Elena Rodrigueza.

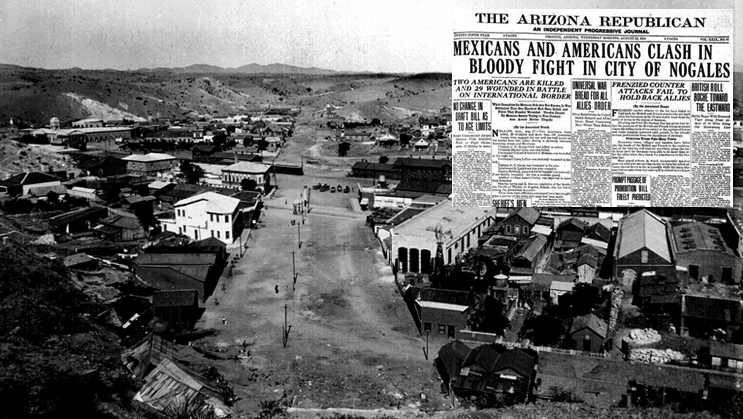

The Battle of Ambos Nogales

The border running through Ambos Nogales is rich with history. This year is the 100th anniversary of two things, the armistice ending World War One and what is called the August 1918 Battle of Ambos Nogales. The battle began with a shoot-out in the customs area between the US and Mexico, an area now characterized by retinal scans of everybody going north into the US. We all breezed south with our signs and puppets into Mexico but had to wait in an hour-and-half long line to get our papers checked and our retinas scanned, lest a threat to America might slip into our midst. Like today, back in 1918, there was considerable tension along the border. Smugglers were an issue. The Mexican Revolution was on-going, which created tension along the border. Also, in the midst of WWI, German military agents had been stirring up the Mexicans with the idea of re-taking the US southwest, which had once belonged to Mexico.

(At top, the open swath of ground that was the border at the turn of the 20th century. And a current shot of the Arizona/Sonora desert.)

Like many wars, this tiny war began out of confusion. A Mexican carpenter was moving with materials from the US side to Mexico. He had technically passed into Mexico when a US customs agent, figuring he was smuggling something, ordered him to return to the US side. Mexican customs officials told the man to ignore the US customs agents. At this point, a US army private raised his Springfield rifle to make the carpenter back up. He apparently let loose a warning shot, which caused the carpenter to quickly drop to the floor. A Mexican agent thought the carpenter had been shot, so he opened fire with his pistol, killing the US army private. All hell broke loose, and there was a brief shootout. The carpenter and others either hunkered down behind something or ran for their lives.

The US military went into action. Units were sent to secure the high ground around Nogales. Black US buffalo soldiers from Fort Huachuca’s 10th Cavalry were sent into the streets of Nogales. During the fighting, the mayor of Nogales, Mexico, tried to stop the carnage by stepping into the street with a white handkerchief tied on his cane. He was hit and killed by a shot that came from across the border on the US side.

Examples of civilian Mexican heroism have been historically honored. These included local prostitutes from the red-light district, two of whom were wounded. These women ventured into the street under fire waving painted red crosses and carrying bed-sheets to minister to the wounded. An account by 10th Cavalry First Sgt. Thomas Jordan reports a soldier being recognized by one of the women. “‘Sergeant Jackson! Are we all glad to see you!’” he writes in his account. “Not now, honey,” was apparently the reply. (As a US army soldier who served a year at Fort Huachuca in the late 1960s, I can attest that such interactions between lonely US soldiers away from home and Mexican ladies of the night is nothing unusual nor dishonorable.)

By the time a cease fire was declared, two US persons had been killed and 29 wounded; on the Mexican side, the numbers are less certain, but at least 125 were killed and some 300 wounded. An investigation laid the blame for the incident on resentment among nogalenses over routine mistreatment of Mexicans by US border agents. It seems little has changed. One Mexican official honored “the many Mexican civilians who laid down their lives in fitting protest against such humiliating and unjust conduct toward them.”

In Nogales, Sonora, there are three monuments or plaques honoring the heroes and victims of the battle. A ballad called “El Corrido de Nogales” honors heroes of the battle and was written by participants — here performed in Spanish. In the US, the incident has been lost to obscurity; the only legacy in the north is the construction after the battle of a fence and the establishment in 1924 of the US Border Patrol and the current introduction of retina-scanning and other technologies being done in the photo below in Nogales.

Today’s Border

One hundred years on, in the craziness of 2018, the US/Mexico border is an armed camp with more and more guns pointing south and a post-truth US president demonizing our Latin American neighbors. They’re “rapists” and “killers” and they carry rot and diseases that are somehow going to seep across the border and ruin our “precious bodily fluids” — to borrow the ludicrous concern of mad General Jack Ripper from Doctor Strangelove. Of course, the fictional General Ripper’s madness fomented the end of the world by triggering the Russian Doomsday Machine.

There is no human reason why a more dignified, more humane border cannot be conceived and worked out — one that does not rely on violence to the extent the one we have now does. Ending the inhuman, supply-focused failure of the many-decade old US Drug War would be a great place to start. A better understanding and focus on the incredible US demand for drugs (versus using the military to stop the supply) would be a very fruitful approach. A number of Latin American leaders have asked US leaders to do exactly this — to little effect. We choose to stigmatize others and use violence rather than analyze and better manage our own weaknesses and desires. Instead, as we did 100 years ago, we rely on an arrogant sense of US exceptionalism, the concomitant mistreatment of Mexicans and Central Americans and, of course, violent military force.

Little seems to have changed since 1918; the issues just get wrapped up with modern technological advances as the problems get darker and seem ever more insurmountable. The Encuentro this past weekend (above) organized by the School of the Americas Watch, Veterans For Peace and other organizations may have been relatively small when compared to the immense problem of a US militarized border. But it expressed the right idea: Intelligence, love, and respect between North Americans and Latin Americans is the only formula that can solve this worsening problem — versus exacerbating it by demonizing our neighbors and putting more agents and more soldiers with weapons on the border.

It’s a political choice. Let’s hope enough North American citizens over the next couple years can improve on the advances made in the recent election. Also, let’s hope the real story of the Honduran coup can come out to explain how it is North American gringos who have put Hondurans between a rock and a hard place.

Finally, two demonstrators who inspired me: Sally Alice Thompson is well into her nineties and a seasoned veteran of anti-war activism; while Luna, who roamed widely among the demonstrators, is just starting out in the business of speaking truth to power.

All Encuentro photos by John Grant