If all else fails, lower your standards.

This has been my philosophy for years. My wife likes to joke it’s how she picked me; instead of prince charming, I’m “prince somewhat-charming.” So you can imagine how delighted I am that the United States of America and its NATO military allies have decided to apply that philosophy to US foreign policy in Afghanistan.

They’re calling their version “Afghanistan Good Enough.”

The notion of lowering ones standards to get out of a human mess is, of course, not my idea. The idea resides in the Pragmatic wing of philosophy and shares something with the Alcoholics Anonymous Serenity Prayer, which is attributed to Reinhold Niebuhr, who stole it from the Greek slave and stoic philosopher Epictetus, who probably borrowed it from some poor slob in chains breaking stones in a quarry in Asia Minor.

Here’s how Alcoholics Anonymous phrased the idea:

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

The courage to change the things I can,

And the wisdom to know the difference.

The point is, if you’re struggling with a monkey on your back — whether it’s an addiction to booze or keeping up with the Myth of American Exceptionalism — your life will be more serene and you will be more content with yourself if you drop the unrealistic expectations you’ve set for yourself or that someone else has set for you.

President Obama in a NATO mood in Chicago and soldiers in Afghanistan

President Obama in a NATO mood in Chicago and soldiers in Afghanistan

So after ten years of trying to control Afghanistan militarily, US/NATO war planners have lowered their standards and, with the help of their top-of-the-line, multi-billion-dollar public relations wing, they came up with the stirring slogan “Afghanistan Good Enough.”

On one hand, this is a good thing. After running a macho campaign on war in Afghanistan to cover its right flank and get elected, the Obama administration has realized the can-do enterprising attitude that defines American Exceptionalism can’t turn Afghanistan into a Jeffersonian democracy. It may have sounded good for a while, but it just isn’t working.

There’s the rugged terrain that makes centralized government impossible, and there’s the deep-rooted corruption. There’s also the deep-rooted corruption of the United States to recognize and the need to focus on the economic debacle at home, a disaster fed by the Afghanistan and Iraq wars and a debauch of deregulation. In a word, Plutocracy.

The problem with “Afghanistan Good Enough” is that it suggests the United States is finally leaving Afghanistan. One can be forgiven for thinking this because that’s exactly what was projected out of the NATO conference in Chicago. And in some sense it’s true. But we live in an incredibly complex society whose leadership is still caught in the headlights of 9/11, and every day seems to reveal more and more compromises with liberty attributable to four current obsessions: Security, Secrecy, Surveillance and Subterfuge. It’s a runaway train on which the average citizen doesn’t stand a chance.

So we’re not really leaving Afghanistan; we’re having an Oprah “make-over” moment. The fat, tired, sluggish democracy champ will disappear backstage, and when the curtain rises he’ll be a lean and mean special operations stud with links to a nerd controlling a lethal drone. Our military isn’t going anywhere; it’s just becoming more focused and more secret, especially to those in whose name it’s used. So just sit back in front of your TV set and relax.

Ayn Rand, Moral Guide For Our Military and Financial Leaders

Last night I read a speech by Ayn Rand, the grand dame of Objectivism, given to the 1974 graduating class at West Point.

She tells the West Point cadets that every person needs a philosophy in order to operate in the concrete world. If you don’t rationally forge your own, one will be foisted on you by others or by the natural chaotic processes of the unconscious. She tells the future Army officers that forging a philosophy begins with the metaphysical (the nature of existence), moves on to epistemology (how we know what we know) then to ethics (what’s good and what’s bad) and to politics (the kind of society we want) and finally on to aesthetics, which she calls “the refueling of man’s consciousness.”

In her speech, Rand constantly loops back on her theme of individuals thinking for themselves and not being part of the herd. It’s a theme I personally love. The problem is she always seems to end up suggesting that to correctly think for oneself one has to think exactly like she does and accept selfishness as a moral goal.

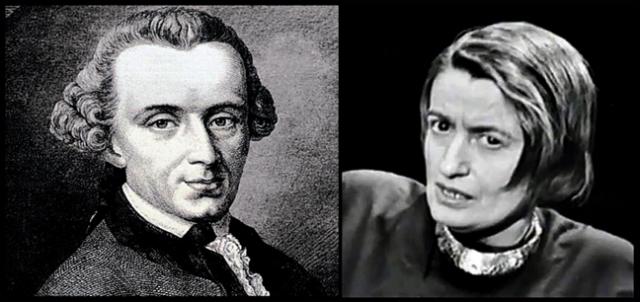

The selfless Emmanuel Kant and the selfish Ayn Rand

The selfless Emmanuel Kant and the selfish Ayn Rand

Born in St Petersburg, Russia, Rand was 12 when the 1917 revolution occurred. After the revolution, she studied literature and screen arts, but ran afoul of the Bolsheviks due to her bourgeois background. In 1925, she got a visa to the United States and became dazzled by Hollywood and screenwriting. She grew into a devoted advocate of laissez-faire capitalism and eventually gathered many acolytes to her ideas. One of the most renowned was former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, who says of Rand in a book blurb: “Ayn Rand’s writings have altered and shaped the lives of millions.”

Greenspan, as we all know, was the financial Oracle at Delphi who intoned before Congress in well-wrought paragraphs of enigmatic gibberish that amounted to cheerleading for the unregulated free-for-all of financial selfishness that led to the economic debacle we’re still living through.

Whether or not Ayn Rand was a “philosopher” is debatable. What’s important is she was an excellent storyteller and a powerful shill for selfishness and greed. Her argument was basically that of a sociopath unburdened with a conscience. William Deresiewics recently wrote a New York Times op-ed called “Capitalists and Other Psychopaths” in which he pointed out the heavier than normal concentration of psychopaths on Wall Street. (Some prefer the softer term sociopath.)

“A recent study found 10 percent of people who work on Wall Street are ‘clinical psychopaths,’ exhibiting a lack of interest in and empathy for others and an ‘unparalleled capacity for lying, fabrication and manipulation.’” He cites the documentary The Corporation in which the point is made that if a corporation is the same as a person — what beneficiaries of Capitalism like Mitt Romney are wont to stress — that person is a psychopath “indifferent to others, incapable of guilt, exclusively devoted to [his or her] own interests.”

So its logical that Ayn Rand might be asked to speak to the graduating class of West Point in 1974, a juncture vis-à-vis the Vietnam War that might have been the lowest point when it came to military morale. They needed a real philosophical cheerleader for American Exceptionalism. A realistic alternative was unimaginable. For some reason, I envision Jonathon Winter’s Colonel Winglow as an alternative speaking to the gathered cadets:

“OK, men, keep up your can-do spirit. And don’t forget, when you get to Vietnam keep your eyes and ears open for fragmentation grenades tossed into your hootch. And don’t let those miserable, whining slopes get to you. They really love napalm.”

Rand told the young cadets to reach down deep and build up a philosophy to oppose all the collectivist America-haters she said were out there intent on undermining the fact “the United States of America is the greatest, the noblest and, in its original founding principles, the only moral country in the history of the world.” Collectivist America-haters, she told them, were all operating on a philosophy rooted in the Categorical Imperative of the 18th century German philosopher Emmanuel Kant, whose philosophy suggested human morality had something to do with compassion and selflessness.

Stick to your high standards, Rand told them. “There may be individuals in your history who did not live up to your highest standards. …[But] honor is self-esteem made visible in action.” We know you won’t let the cult of selfishness down over there in the villages and rice paddies of Vietnam. Go get ’em!

As Greenspan found out in the financial realm, self-delusion can be a powerful thing until it runs into a wall of reality. It’s at that point — face bloodied from smacking into the wall — that Pragmatists like William James begin to make sense to people formerly for war. Suddenly, delusional standards are a burden and can finally be adjusted to reality.

Here’s James from 1879 describing the philosophy of Pragmatism, what is often described as the most pure American strain of philosophy:

“A pragmatist … turns away from abstraction and insufficiency, from verbal solutions, from bad a priori reasons, from fixed principles, closed systems, and pretended absolutes and origins. He turns toward concreteness and adequacy, towards facts, towards action and towards power. …It means the open air and possibilities of nature, as against dogma, artificiality, and the presence of finality in truth.”

In other words, to borrow contemporary philosopher Harry Frankfurt’s term, cut the bullshit.

Addressing his critics of the “rational” school — which includes Rand who would arrive in America 46 years later formed by communist oppression in Russia — James says this:

“I have honestly tried to stretch my own imagination and to read the best possible meaning into the rationalist conception, but I have to confess that it still completely baffles me. The notion of a reality calling on us to ‘agree’ with it, and that for no reasons, but simply because its claim is ‘unconditional’ or ‘transcendent,’ is one that I can make neither head nor tail of.”

He seems to be saying that if one sees certainty as a human delusion, one either has the humility rooted in that fundamental doubt or the arrogance of egoism that justifies forcing your will on others. This is, of course, on a continuum; everything is a little of this, a little of that.

This split is arguably at the core of our culture wars. One side — represented in spades by Rand at West Point — believes with certainty it’s right and is willing to support that rightness with the use of force and violence. Meanwhile, the other side sees the range of possibilities (what some damn as “relativism”) and, accordingly, emphasizes knowledge, humility and compassion as the means for success in the world.

Unfortunately, violence wins most struggles in the short run.

Coda of an Astronaut Lost In Space

Rand opened her speech to the West Point cadets by telling them a little story. “You are an astronaut whose spaceship gets out of control and crashes on an unknown planet.” She mocks what she sees as the Kantian, relativist mental weaknesses of the age and describes the lost astronaut as unable to decide what to do. “You turn to your instruments. … But you stop, struck by a sudden fear: how can you trust these instruments? How can you be sure they won’t mislead you?”

So the astronaut does nothing. “It seems so much safer just to wait for something to turn up.” He sees two-legged figures approaching him from a distance. “They, you decide, will tell you what to do.”

The astronaut is never heard from again.

Rand’s point is that a smart astronaut — or Army officer — would have acted differently. Most people, she says, act like the passive astronaut, evading three questions: “Where am I? How do I know it? What should I do?”

While she didn’t spell it out, there’s an implication in her story that a smart astronaut would have concluded (as her story implies was the case) the approaching figures were hostile and would have gunned them down preemptively.

Rand doesn’t discuss the other possibility, that the approaching figures were friendly and ready to help the lost astronaut — like Native Americans in the Thanksgiving story. In that case — a circumstance the United States Army is very familiar with — the gunned down figures would be tragic casualties of the fog of war.

But don’t fret. Public affairs officers would be sent to the planet later to pay the families an appropriate sum for the loss of their loved ones.