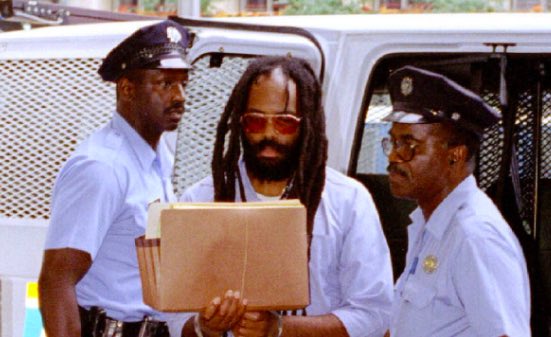

In a huge potential break in the long-running and controversial case of Philadelphia journalist Mumia Abu-Jamal, currently in Pennsylvania’s SCI Mahanoy prison serving a life-without-parole term for murder, the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office says it has discovered six banker storage boxes of materials about the case in a locked storeroom of the DA’s offices at 3 South Penn Square.

The boxes, spotted by Krasner himself during a search of the previously locked storeroom for an office desk, reportedly had the name “McCann” scrawled on their facing side, apparently referring to Edward McCann, the long-time head of the DA’s homicide litigation unit (McCann left the DA’s office in 2015). When the boxes were removed from under the desk, it was discovered that the name “Mumia” was written on the their hidden ends.

Five of the boxes were reportedly numbered 18/29, 21/29, 23/29, 24/29 and 29/29. The sixth box had no number on it. The department’s Mumia case record is stored in boxes numbered 1-32 and includes boxes similarly numbered to those found in the storeroom.

The newly located cardboard crates, which contain case files, evidentiary material and other materials relating to the Mumia case, are going to be provided to the defense for their inspection, according the DA’s office.

The significance of this surprising discovery by Krasner, a prominent progressive defense attorney who won election as DA in November 2017 and moved into the DA’s office last January, is that if those boxes contain any evidentiary material that was improperly withheld from the defense, and if what was withheld proved significant enough that it might potentially have led the original jury to a different conclusion — for example a non-unanimous decision to convict — it would be grounds for seeking a retrial of the case.

Even if such previously undisclosed evidence were less obviously significant, it could open the door for the defense to seek a new Post Conviction Relief Act (PCRA) hearing at the level of the court of common pleas. At such a hearing both sides — the defense and the DA’s office — would be able to make arguments and even, depending on the evidence found, to subpoena witnesses — potentially even witnesses from the original trial who could be re-questioned under oath.

The discovery of the crates comes at a critical juncture for Abu-Jamal, who has spent 29 years on death row and a total of 38 years in prison after having his death penalty for conviction in the 1981 shooting death of white Philadelphia police officer Daniel Faulkner vacated on Constitutional grounds.

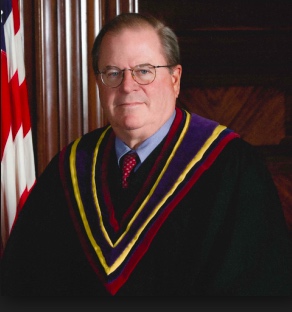

Just two weeks ago , Common Pleas Judge Leon Tucker issued a ruling that four important PCRA appeals by Abu-Jamal, including his first lengthy and contentious PCRA hearing in 1995 at which all of the important evidence in the prosecution’s case was challenged before the original trial Judge Albert Sabo, needed to be re-appealed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Judge Tucker ruled that all four of those appeals, each of which was summarily rejected by the state’s high court, had been unfairly dismissed because one of the Supreme Court justices, Ronald Castille, had, from 1986-1991, been Philadelphia DA, where he was in charge of the assistant DAs tasked with defending against Abu-Jamal’s appeal of his conviction. Tucker said that even if there was no documentary evidence of Justice Castille’s direct involvement in that appeal fighting process, the mere appearance of a conflict of interest meant he should have recused himself from discussions of and deciding on those appeals. Instead, Castille participated in high court’s majority decisions to reject all four appeals.

Following hearings that preceded his ruling, Judge Tucker had ordered a thorough search of the DA’s office in an effort to locate any memos or other documents that might link former DA Castille to his office’s handling of Abu-Jamal’s case. While no Castille memo turned up, Krasner’s office, which had assigned a paralegal to the search, did locate two memos about the case with questions addressed to Castille, but never found his response.

The six crates, interestingly, were discovered on Dec. 28, just a day after Judge Tucker’s ruling was issued.

Krasner’s office still has not responded to the judge’s decision, which would have to be appealed by his office within 30 days, or in other words, by January 26. No other party or agency besides the Philadelphia District Attorney has standing to appeal it, meaning if DA Krasner does nothing, it will stand.

Radio station WHYY, in a local news report today, quoted retired Assistant DA McCann, whose name was on all the newly discovered case document crates, as saying he “doubted” there would be any new evidence undisclosed to the Mumia defense team found in them. McCann suggested that the contents may have been all photocopies of material the defense has already seen.

The defense team, which declined to comment, believes McCann is wrong, and clearly will be going through the materials in the boxes with a fine-tooth comb looking for signs of original copies of evidence not disclosed to the defense at trial. (It’s worth noting that nobody in the DA’s office anticipated that Krasner would take over an office that for generations has been run by hard-line prosecutors less concerned with justice than with winning cases, and willing to bend the rules or overlook police or prosecutorial conduce in order to win convictions.)

The case of Mumia Abu-Jamal, who has become a powerful voice from inside of what he calls the US “prison industrial complex,” whose original trial was widely seen as a corrupt travesty of justice, and whose freedom has been sought by supporters around the world who see the progressive journalist and former Black Panther as a political prisoner, is far from over.

DAVE LINDORFF is author of ‘Killing Time: An investigation into the death-penalty case of Mumia Abu-Jamal (Common Courage Press, 2003).