Years ago while studying in Zurich to be a Jungian analyst, I was exposed to an aura of this great person, Hearing the recounting of some of the exotic dreams of my fellow students only made me more awestruck. It therefore came as a shock when in that setting I dreamt of sitting at a small table across from Jung, a half empty bottle of wine between us, as Jung said in a slurred voice, “Don’t believe everything I say.”

I was on my way.

Jung once said he would have had no interest in dreams if they didn’t have meaning. For thirty years I have been intrigued by Jung’s thoughts on the subject as well as the thoughts of others. Therefore a recent television program on “Why we dream” naturally caught my eye.

It was largely a behavioral study of REM sleep, in which, not to my surprise, Jung’s name went unmentioned.

My purpose here is to introduce some of Jung’s thoughts to a largely uninformed public, and to explain the reason for his omission, which is typical of scientific studies of the dream state, and reports on those studies.

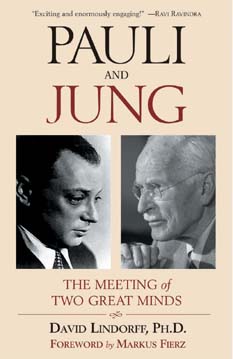

The author's book

The author's book

Early in the 20th century, the depth psychologists Freud (b.1856) and Jung (b.1875) played out the respective rolls of the controlling father and and rebellious son. An inevitable split came when the ‘heir apparent’ could no longer tether his growing need to strike out on his own. This involved his seeing the unconscious (what Freud called the subconscious) as having a limitless depth, which in turn meant the symbolism in dreams are seen as containing a wealth of meanings, so that the dream can be seen to be truly a door to the unconscious. (To Freud, in contrast, a dream had a specific meaning based on sexual repression.)

Jung hypothesized that dreams arising from great depth contained archetypal imagery common to all humanity, though, like the instincts, these are colored by the dreamer’s particular culture. It rests with the individual to find that aspect within her/himself which is authentic. Jung called this process individuation.

One may ask why dreams come from such different depths, or why there is recall of dreams at all. Jung’s answer was to say, “The unconscious responds with the face you turn towards it.” This remark explains why the medical/scientific model steers clear of using the word ‘unconscious.’ A dominant segment of our culture is interested exclusively in things that can be rationally explained. A concept like the unconscious, which is not amenable to controlled experiments, lacks a reality check. My doctor says he believes only what he reads in his medical journals.

Even Jungian practice is opening itself to behavioral theories, which are blind to the unconscious. Is it no wonder that Jung has been left out. And that’s before we even get to Jung’s theory of synchronicity.

It took Jung many years to write about his hypothesis that archetypal dreams can be related to real-world events which would appear to have no causal connection. He called this phenomenon synchronicity. Like ESP, the idea of synchronicity can be hard for a rationally minded person to swallow.

Recently the Red Book of Jung has been published. This massive volume is comprised of a facsimile of his handwritten thoughts together with many colored plates of his art work, created over a ten year period, along with an English translation of his writing. Much of the book relates to conversations with his soul, from which he says he learned so much of his psychology.

To this it must be added that Jung, also an MD, claimed to be a scientist. Speaking as someone who is both an analyst and an electrical engineer, I’d say that if by this Jung is saying he is an astute observer unafraid of breaking with tradition, I can back his claim. Certainly within the realm of quantum physics there are obsevations which can’t be rationally explained. The physicist Wolfgang Pauli, a patient of Jung, hoped that physics and psychology would one day be brought together by a recognition of their interaction.

It is my hope that, along with Jung and Pauli, the theory of synchronicity will ultimately be accepted in a world view where the non-rational and rational can sit comfortably at the same table.

DAVID LINDORFF, Sr. is a retired electrical engineer, a practicing Jungian analyst, and is author of (Quest Books, 2004). He lives with his wife Dorothy in Mansfield, CT, and can be contacted by email. This article was written for ThisCantBeHappening